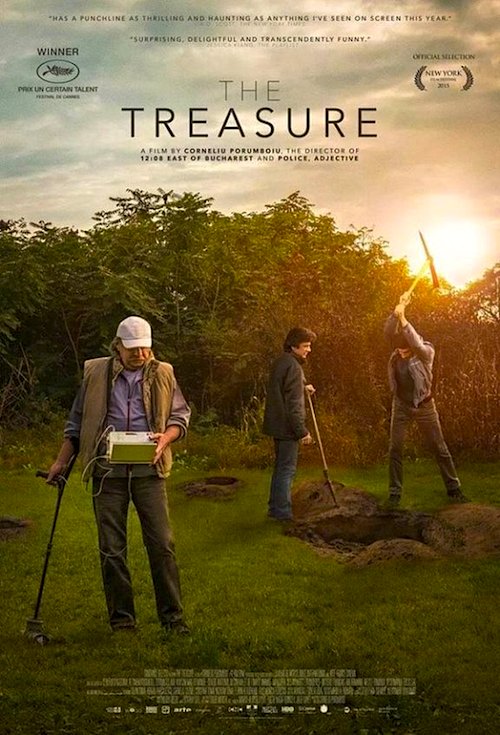

By Joe Bendel. You might call this Romanian style tomb-raiding. Instead of ancient crypts, Costi’s unemployed neighbor invites him to help plunder his own family history. If Adrian’s grandfather really did bury something in his backyard on the eve of the Communist nationalization, the two men hope to find and split it. Of course, that will be a big “if” in The Treasure, Corneliu Porumboiu’s wry comedy of manners and bureaucracy, which opens this Friday in New York.

Facing foreclosure on his flat, Adrian offers Costi a deal. If he can pay the eight hundred Euros necessary for a professional metal detecting service, they will share the proceeds of everything they might find. Based on his late grandfather’s cryptic words to him, Adrian is absolutely convinced there must be something there, sort of how George Bluth, Sr. would say “there’s always money in the banana stand.”

For a mild mannered government office worker like Costi, eight hundred Euros represents a considerable investment. Just taking time away from work to schedule the appointment arouses his supervisor’s suspicions, in an absurdly droll scene that could very well be a defining example of Porumboiu-ism. However, Cornel offers them an off-the-books special behind his boss’s back. For half the price, he agrees to meet them with the gear in Islaz, the site of the 1848 democratic uprising. However, they must be secretive about their scheme, because the government is entitled to claim anything deemed to have national cultural significance.

Given the discreet, severely reserved nature of Porumboiu’s style, you might not realize in-the-moment how much lunacy unfolds during The Treasure. It has the heart of It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad World, but the tone of Porumboiu’s “greatest hit,” Police, Adjective. However, whenever a supposed authority figure saunters into the frame, the absurdity that follows is impossible to miss. The toxicity of the Communist era also lingers over their best laid plans, like an annoying ghost.

Deceptively stone-faced, Toma Cuzin slowly but surely brings out Costa’s endearing everyman qualities. Adrian Purcarescu, Porumboiu’s filmmaker colleague, whose own metal-detecting exploits inspired the film, is uproariously neurotic as his namesake. Similarly, real life metal-detector Corneliu Cozmei is a pitch perfect Droopy Dog foil for the resentful Adrian. Their caustic bickering is wickedly droll and acutely realistic.

That is also pretty much true of Porumboiu’s film in general. It is as understated as a Stephen Wright monologue, but it builds to an uncharacteristically satisfying conclusion. This is not just Porumboiu’s most accessible film, but perhaps the most reachable and diggable film to be broadly associated with the Romanian New Wave. Highly recommended for sophisticated palettes, The Treasure opens this Friday (1/8) in New York, at the IFC Center.

LFM GRADE: A-

Posted January 6th, 2015 at 9:56pm.