By Joe Bendel. Forget the Syfy (Sci-Fi) Channel’s Earthsea miniseries. Ursula K. Le Guin, the author of the Earthsea novels and stories, would certainly prefer you did. Her reaction to Gorō Miyazaki’s anime adaptation of her fantasy world has also been decidedly mixed, but arguably not as vehement. In fact, Miyazaki’s film is not without merit, especially for those not intimately grounded in the Earthsea mythology. Three years after its Japanese premiere, Miyazaki’s Tales from Earthsea, finally has its American theatrical release, now screening in select theaters courtesy of Walt Disney.

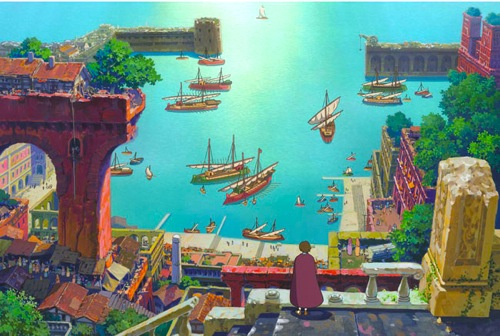

While the legendary Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki long sought to adapt Le Guin’s Earthsea stories, it was his son Gorō, a relative new comer to animated filmmaking, who was assigned the project by Studio Ghibli, the anime house co-founded by Miyazaki the elder. The result is a visually striking, if thematically familiar, fantasy.

Like the epics of Tolkien and Robert Jordan, Tales follows a young protagonist of destiny, Arren, a confused prince who has apparently just murdered his father, the king. Fleeing in shame, he encounters the wizard Sparrowhawk on the road. Like his late father, Sparrowhawk is concerned about the chaos sweeping over Earthsea. The weather is unseasonable, crops are failing, livestock are dying, and two dragons were recently spotted off the coast fighting to the death – an unprecedented event in the Earthsea fantasy world.

Naturally, there is a Sauron-like evil overlord to contend with. In this case, it is the androgynous sorcerer Cob, whose slave-trading minions are out to get Arren. Indeed, Tales follows the standard epic fantasy template, but does so reasonably well. There is also a pseudo-environmental motif of a world out of balance that should have appealed to Le Guin, but it is subtler and more nuanced than most “green” movie messages.

Miyazaki the younger is most successful creating an epic look in the film, employing watercolor backgrounds and hand-drawn animation for dramatic effect. Indeed, his fantasy landscapes and cityscapes have an exotic beauty that elevates Tales well above standard issue anime.

Redubbed for an American audience (not an uncommon practice with anime distribution), the English language cast mostly ranges from adequate to fairly good. Timothy Dalton (the under-appreciated James Bond) is the class of the field, lending his commanding voice to Sparrowhawk. In contrast, Willem Dafoe’s work as Cob often sounds campy, in the wrong way.

The first Disney animated release to carry a PG-13 rating, Tales is similar in intensity (and subject matter) to Ralph Bakshi’s 1978 animated Lord of the Rings. Richly crafted but predictable (as is the case with most contemporary fantasy fiction), Tales is better than genre diehards might have heard at their conventions. It is currently screening in New York at the Angelika Film Center, and in Los Angeles at The Landmark.

Posted on August 20th, 2010 at 8:11am.