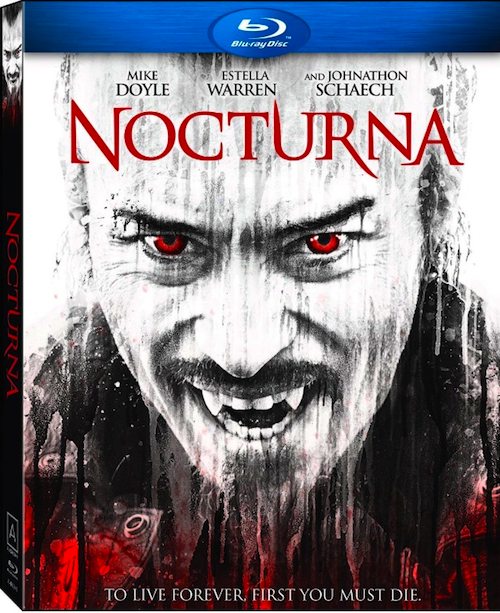

By Joe Bendel. It makes sense vampires are drawn to New Orleans. The city is unusually preoccupied with its cemeteries and mausoleums. Still, you would think that whole below-sea-level thing would complicate their undead rest, but two antagonistic vampire clans have found safe lairs. However, two rogue cops intend to root out the sadistic Molderos, as long as they enjoy the protection of their rivals by night. Of course, it gets messy when humans and vampires mingle in screenwriter-director Buz Alexander’s Nocturna, which releases this week on DVD, Blu-ray, and VOD from Alchemy.

Harry Ganet is a bitter, grizzled NOPD veteran, who is less than thrilled to be baby-sitting his new partner, the mayor’s gung-ho nephew Roy Cody. There is just no talking to the green detective when they find a so-called “Parish Kid,” one of the waifs branded with a vampire clan’s insignia. The term comes from the mysterious empty parish where they live, waiting to be sucked dry of blood or turned into vampires themselves. Cody figures he march right over and give the girl’s captors a stern talking to, but it does not work out so well for anyone.

The upshot is the Molderos are out to get Ganet and Cody, so the slightly less sinister Brisbane offers them a deal. They can crash at his crib during nights, if they sleuth out the Moldero resting places while the sun is up. Despite his surly attitude, Ganet seems more inclined to accept their hospitality than Cody. Perhaps it has something to do with Lydia Sonata, who also holds a grudge against the Molderos. She was once one of their branded possessions, but Brisbane rescued and turned her.

Granted, Nocturna is more than a little rough around the edges, but it combines elements of the Anne Rice and Underworld mythoi in interesting ways. Yet, Alexander does not share their erotic or action-oriented approaches, focusing instead on the grudges and betrayals of the respective clans and the human interlopers. Frankly, the pseudo-triangle of Sonata, Ganet, and Brisbane is more intriguing than you would expect, because of the supernatural implications of the relationships in question.

Granted, Nocturna is more than a little rough around the edges, but it combines elements of the Anne Rice and Underworld mythoi in interesting ways. Yet, Alexander does not share their erotic or action-oriented approaches, focusing instead on the grudges and betrayals of the respective clans and the human interlopers. Frankly, the pseudo-triangle of Sonata, Ganet, and Brisbane is more intriguing than you would expect, because of the supernatural implications of the relationships in question.

Mike Doyle and Mariana Paola Vicente actually display strong screen presences and develop interesting chemistry together as Ganet and Sonata. Danny Agha’s impossibly naïve Cody gets a little tiresome, but after the first act set-up, he disappears for long stretches at a time. As the respective clan leaders, Johnathon Schaech and Billy Blair are the sort of gothy strutting vampires we have seen innumerable times before, but the nearly unrecognizable Estella Warren plays the Moldero queen with a Mommie Dearest edge that is certainly disturbing.

Frankly, Alexander could have used some help coordinating his fight scenes, as well as some more convincing stunt personnel. Nevertheless, he maintains a reasonably creepy vibe and soaks up plenty of atmosphere from Baton Rouge and the Parishes outside New Orleans, where Nocturne was shot (we’d ordinarily complain about the lack of jazz and zydeco on the soundtrack, but these vampires just do not seem like the hip jazz sort of undead). It is just sort of okay, but there have certainly been less auspicious debuts. For those who support NOLA/Louisiana film production, Nocturna releases today (10/6) on various home viewing formats.

LFM GRADE: C+

Posted on October 6th, 2015 at 11:31pm.