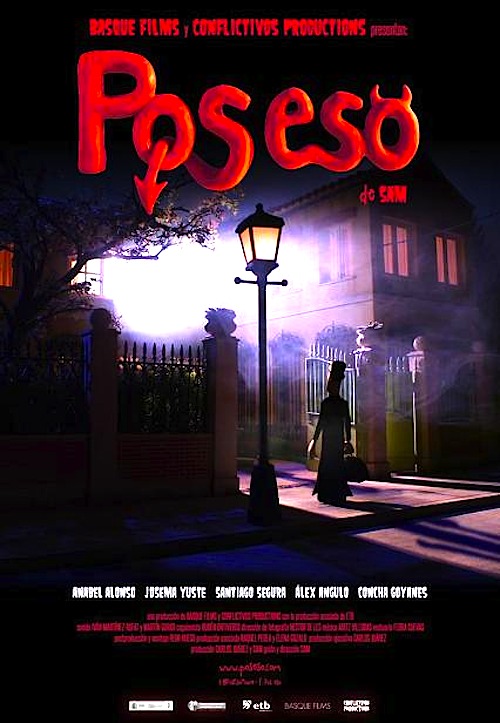

By Joe Bendel. When Franco was around there wasn’t any demonic possession in Spain. The Generalissimo simply wouldn’t stand for it. Things are different now. Everyone soul is vulnerable to infernal forces during these godless times, even the son of the country’s favorite matador and flamenco dancer. His name is Damien, by the way. You can watch his head spin around and projectile-vomit in Claymation courtesy of Sam [Samuel Ortí Martí]’s Possessed, which screens tonight during the 2015 Fantasia International Film Festival in Montreal.

Trini was once the greatest dancer Spain had ever seen, but she retired from public performance after her husband’s untimely death. While grief-stricken, she also believed her son Damien needed more attention. He is a bit of a strange kid, who is prone to disruptive behavior at school. She has had him examined by child psychologists, but they are never around long enough to do much good. Her mother-in-law is convinced the boy is possessed, but her obtuse manager remains skeptical.

Eventually, Trini accepts the wild supernatural bedlam going on around them and seeks the Church’s assistance. Unfortunately, the corrupt Bishop will not be much help in a fight of good against evil. She needs the righteous, but disillusioned Father Lenin, the black sheep son of 1930s Communists.

Eventually, Trini accepts the wild supernatural bedlam going on around them and seeks the Church’s assistance. Unfortunately, the corrupt Bishop will not be much help in a fight of good against evil. She needs the righteous, but disillusioned Father Lenin, the black sheep son of 1930s Communists.

If ever there was a Claymation movie unsuitable for kids it would be Possessed. In addition to the demonic horror, there is what you might call graphic cartoon violence. Plenty of mature subject matter is also referenced, but that is small potatoes compared to the faces that get lopped off. Call it a double standard, but if Possessed were a live action film it would be rather disturbing, yet it is all pretty funny in an animated film. Think of it as Wallace & Gromit torturing Mr. Bill in Hell.

Yes, “Sam” and co-screenwriter Rubén Ontiveros’s anti-Catholic attitudes get tiresome, but they are stuck with the fundamental High Church world view inherent in the demonic horror genre. They also dig their flamenco, which counts for something. Ultimately, you just can’t nitpick such gory and scatological humor.

Trust me, you have never seen clay like this. While the craftsmanship is not quite at the level of the Aardman Studios, it is certainly impressive in its own way. Recommended for fans of The Exorcist films and Team America: World Police, Possessed screens today (7/19) and Friday (7/24) as part of this year’s Fantasia.

LFM GRADE: B

Posted on July 19th, 2015 at 6:25pm.