We love this. Part II will run tomorrow. Enjoy …

Posted on October 6th, 2010 at 9:07am.

We love this. Part II will run tomorrow. Enjoy …

Posted on October 6th, 2010 at 9:07am.

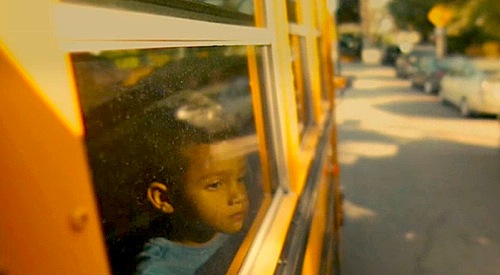

By Patricia Ducey. Waiting for Superman is an emotionally gripping and ultimately devastating critique of the American public school system, in the same vein as The Lottery or The Cartel and a host of previous education movies. Superman focuses on a half dozen children and their families – and their desperate quest to gain admittance to their city’s charter school. There are only a few spots in each school and many applicants; the filmmakers draw us in and–let’s be honest–manipulate us with the suspense leading up to what is characterized as a make-it-or-break-it day when the charter school chooses its next class by lottery. Will these children escape their neighborhood “dropout factory” and secure their futures?

Co-written with Billy Kimball, directed by Davis Guggenheim (An Inconvenient Truth) and produced by Jeff Skoll’s Participant Productions, this documentary possesses an authentic progressive pedigree. Skoll views films as vehicles for social change, a kind of “loss leader” that delivers butts in the seat to the alliances and activists he has already mobilized to capitalize on them (see here) and he hopes to do the same with Superman. Skoll greenlights pictures that conform to his own world view, as he is of course entitled to, and sometimes departs from expected liberal orthodoxy – as when he reportedly turned down Michael Moore for Sicko funding. The Canadian Skoll knows from personal experience the failures of nationalized health care. Superman takes aim at a few surprising targets, as well – like teachers’ unions and government bureaucracies.

The film opens with Guggenheim driving by three public schools in his neighborhood on his way to drop off his own kids—at a private school—and recalling his first education documentary of 1999, The First Year. Nothing has changed since then, he muses with regret, and thus was born the idea of Superman.

The film opens with Guggenheim driving by three public schools in his neighborhood on his way to drop off his own kids—at a private school—and recalling his first education documentary of 1999, The First Year. Nothing has changed since then, he muses with regret, and thus was born the idea of Superman.

Most of the children are poor in the film, and all of them are trapped in schools determined by where each family lives. One of the subjects of the present film, a fifth-grader named Anthony, is being raised in Washington, D.C. by his grandmother. His father is dead from a drug overdose; he never knew his mother. He wants to get a better education yet he doesn’t want to leave all his friends. He answers “bittersweet” when asked how he would feel if he really did win the lottery to get into SEED, a DC boarding school for inner city kids. This is what’s left for him, a child already burdened by loss, in DC, the film says, yet not one word about the voucher program in DC or President Obama’s phasing out of that city’s successful program.

But Superman does take on Democrat and Republic legislators alike and their alliance with what it considers the real enemy, the bulging PAC funds of the teachers’ unions. And the film praises bipartisan cooperation, too – specifically, that between the late Ted Kennedy and then President G. W. Bush that produced No Child Left Behind. Many people, though (including me) questioned that “unity” because it represented more government control – not less – of a problem that government itself caused.

This is where Superman goes irretrievably wrong. We endure the painful story of these beautiful children and their dedicated parents only to be urged on to … what? Send a text to Skoll’s website for mobile updates? Write an astroturfed letter to our governors, urging them to adopt a new blizzard of education standards? These have been formulated by Skoll’s assemblage of experts and appear to be a workaround for NCLB. I question how and why these experts arrived at their conclusions. The fact that they are unelected does not bode well, either, for future responsiveness to parents.

Superman has all the smart facts. Reading and math scores have not improved in 30 years; a number approaching 50% of our children do not graduate from high school at all. I would ask, then, why are solutions like distributing vouchers or dismantling the Department of Education (founded roughly 30 years ago) and returning schools to local and parental control considered too radical? Let it be said that I know many wonderful teachers and public employees, as well. I want to emphasize that the problem is mandatory union membership and union alliances with politicians and non-education groups. In Superman, we see placards at “teacher” protests against Chancellor Michelle Rhee from the ubiquitous ANSWER, for instance, indicating that something other than local education issues are at stake.

Slick websites and tweets and texts do not constitute a real answer to the problems presented by this otherwise moving film. Adding to the sticky quagmire of federal, state, and local rules and regulations for education, rightfully lamented by the film, will not cure the problem or force accountability. Freedom to choose just might. Why not reduce top-down solutions like national standards and national experts, and empower individual parents and local communities? Superman rightfully rues the lottery system, necessitated by the scarcity of truly effective charter schools now in operation. But how do we empower individuals? The voucher system, to me, represents a much quicker, more elegant solution.

Guggenheim is free to choose what he thinks best for his children because he has the money to pay for tuition. He feels terrible about it. But the Superman parents have money, too, available to them. It’s just that the government and their handmaidens – the education unions – mediate the transaction between family and school.

The only true accountability for schools will be realized when parents can vote with their kids’ feet, and take their voucher and their child to another school. The answer to bureaucratic failure is never more bureaucracy. The answer is freedom – because the answer is always freedom. I hope that the families who send their children to school every day know, like Guggenheim, that it’s ultimately their own free choice where they send them.

Posted on October 5th, 2010 at 10:36am.

By Joe Bendel. There was a time when Nicolae Ceaușescu got all the Iron Curtain’s favorable press. Many in the foreign policy establishment considered him reasonable, even reform-minded based on some shrewd public relations moves, like his measured criticism of the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. However, the 1989 Revolution ripped down the façade, revealing to the world the monster that had long oppressed Romania. Of course, every dictator sees himself as an enlightened Caesar – and has the state-produced propaganda to prove it. Culling 180 minutes from over 1,000 hours of archival footage, Romanian director Andrei Ujică assembled a video-collage of Ceaușescu’s life as it was perceived by the dictator and recorded by his state cameras in The Autobiography of Nicolae Ceaușescu (trailer above), which screens this Saturday during the 2010 New York Film Festival.

Defiant to the end, Nicolae Ceaușescu refuses to cooperate in the hastily assembled trial following the Revolution (he would say coup) that removed him from office. Indeed, his has been a life of destiny as we watch his storied career in flashbacks, courtesy of the state propaganda ministry.

From his meteoric rise following the death of his Stalinist mentor Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, Ceaușescu might have displayed a bit of independence in foreign policy – but aside from his support for Prague Spring, this usually manifested itself in uncharacteristically warm relations with the Warsaw Pact’s Eastern rivals, the Chinese and Vietnamese (here was a man who could appreciate a personality cult). Still, he certainly seemed to enjoy entertaining western heads of state, including President Nixon (who also appears to relish his photo ops with one of the few world leaders he physically towered over). We watch as Ceaușescu celebrates birthdays, receives dignitaries, and opens party conferences. He briefly condemns a spot of hooliganism in Timişoara and then suddenly he is facing an ad-hoc inquest. Of course, the real story is much more dramatic and far bloodier.

From his meteoric rise following the death of his Stalinist mentor Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, Ceaușescu might have displayed a bit of independence in foreign policy – but aside from his support for Prague Spring, this usually manifested itself in uncharacteristically warm relations with the Warsaw Pact’s Eastern rivals, the Chinese and Vietnamese (here was a man who could appreciate a personality cult). Still, he certainly seemed to enjoy entertaining western heads of state, including President Nixon (who also appears to relish his photo ops with one of the few world leaders he physically towered over). We watch as Ceaușescu celebrates birthdays, receives dignitaries, and opens party conferences. He briefly condemns a spot of hooliganism in Timişoara and then suddenly he is facing an ad-hoc inquest. Of course, the real story is much more dramatic and far bloodier.

More or less billed as an object lesson in film as a propaganda tool, Ujică did not set out to create a revisionist history or to humanize the permanently deposed dictator. However, the film might have that unintended effect on audiences not privy to Ujică’s underlying concept or his past work documenting the 1989 uprising in Videograms of a Revolution. This is a particular risk here in New York, where art-house patrons consider themselves politically sophisticated but are easily manipulated by propagandistic images exactly like those in Autobiography.

Running a full three hours, Autobiography is a hugely ambitious work, but frankly it is a grueling viewing experience. One scene of Ceaușescu fondling the bread of a well-stocked Potemkin market during a photo op makes the point. The second constitutes overkill. In fact, there is constant and deliberate repetition throughout Ujică’s film, as each Party conference and state visit blends into the next. Perhaps this is a deliberate strategy to convey the rigidly homogenous nature of Ceaușescu’s artificially constructed reality, but it is wearying for viewers looking for a lifeline to grasp unto.

As the highly problematic Autobiography currently stands, there is no footage that even mildly criticizes Ceaușescu’s twenty-five year misrule. How could there be? Any employees of the propaganda ministry not properly lionizing their master would have faced severe (probably fatal) reprisals. As a result, the entire film is much like Kim Il-sung’s massive welcoming ceremony, a hyper-real but static spectacle, ironic in its conspicuous lack of irony. Ujică proves himself a daring filmmaker, but to what end? Autobiography is ultimately a film for those who have an affinity the vintage aesthetics of the Soviet era, regardless of the messy history involved, essentially unreconstructed leftists and ironic hipsters. Not recommended, it nonetheless screens this Saturday (10/9) at the Walter Reade Theater as a special presentation of the 48th NYFF.

Posted on October 4th, 2010 at 9:13am.

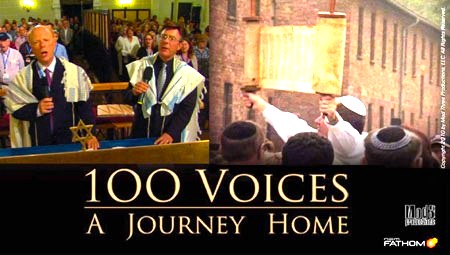

By Joe Bendel. There were more righteous gentiles from Poland than any other country. No strangers to suffering, three million Poles also died under National Socialism, while the Polish resistance forces were the only organized underground with a division specifically dedicated to saving Jewish lives. Yet, the Nazis were grimly successful cleaving apart Polish and Jewish culture, though they had been closely intertwined for centuries. In an effort to mend that breach, a group of 72 cantors made an emotional tour of Poland last June, fortuitously captured in Danny Gold and Matthew Asner’s documentary 100 Voices: A Journey Home, which began a limited engagement in New York and Los Angeles last Wednesday, following a special nationwide one-night event-screening this past Tuesday.

Tuesday’s special screening was presented under the auspices of NCM Fathom, the in-theater event specialists, which is particularly apt considering their specialty simulcasting opera. Indeed, there is a strong affinity between opera and the cantorial music of Voices. In fact, the father of two tour participants probably saved his life during the Holocaust by convincing the Nazis he was an opera singer rather than a cantor. While their music is liturgical, most cantors’ delivery is expressive and dramatic, bearing a strong stylistic resemblance to full-voiced opera singing.

After providing viewers an essential grounding in cantorial music and great cantors past (including the jazz-influenced Moishe Oysher), Voices follows the cantors on their eventful tour, organized by the forceful Cantor Nathan Lam of the Stephen S. Wise Temple in Los Angeles. Adding additional tragic significance, Polish President Lech Kaczyński was in attendance for their tour-opening command performance at Warsaw’s National Opera House mere weeks before his fatal plane-crash. It was a heavy program featuring an original composition penned by Charles Fox (probably best known for “Killing Me Softly”) inspired by Pope John Paul II’s simple prayer left at the Western Wall.

After providing viewers an essential grounding in cantorial music and great cantors past (including the jazz-influenced Moishe Oysher), Voices follows the cantors on their eventful tour, organized by the forceful Cantor Nathan Lam of the Stephen S. Wise Temple in Los Angeles. Adding additional tragic significance, Polish President Lech Kaczyński was in attendance for their tour-opening command performance at Warsaw’s National Opera House mere weeks before his fatal plane-crash. It was a heavy program featuring an original composition penned by Charles Fox (probably best known for “Killing Me Softly”) inspired by Pope John Paul II’s simple prayer left at the Western Wall.

Yet, the next performances were probably even more personally moving for the cantors, including memorial performances at Warsaw’s only surviving synagogue and at the gates of the Auschwitz concentration camp. However, the tour ended on a hopefully note, culminating with an open-air concert at the Krakow Jewish Cultural Festival, organized by the Catholic Janusz Makuch. Embracing the term “Shabbos goy” Makuch has worked to foster an appreciation of Poland’s Jewish heritage since 1988 (an effort greatly aided by the fall of Communism in 1989).

While the music of Voices may not be to all tastes, precisely for its operatic quality, there is no denying its power. Beautifully recorded and presented by directors Gold and Asner with cinematographers Jeff Alred and Anthony Melfi, it should lead to a deeper and wider appreciative of cantorial music, certainly outside Judaism and perhaps within the faith as well.

Indeed, Cantor Lam’s project was notable not just for the size of the tour, but the noble intent. Recently, many religious leaders have acted provocatively, even insensitively, while claiming the mantle of intolerance (yes, I definitely mean the organizers of the World Trade Center mosque here). However, the Voices tour really was undertaken in the spirit of tolerance, seeking to strengthen ties and understanding between faiths and people. A well intentioned film executed with grace and dignity, Voices deserves an audience well past Oscar season. It plays in select theaters in New York and Los Angeles through September 28th.

Posted on September 26th, 2010 at 12:08m.

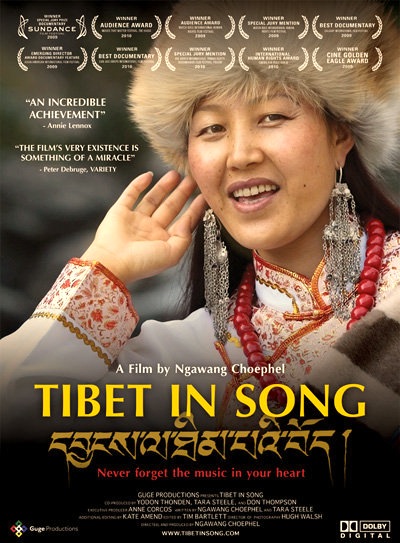

By Joe Bendel. It can honestly be said Ngawang Choephel’s debut documentary was over six and a half years in the making. That is how long he was unjustly imprisoned by the Chinese Communist government for the crime of recording traditional Tibetan folk songs. Of course, they called it espionage. What started as an endeavor in ethnomusicology became a much more personal project for Ngawang, ultimately resulting in Tibet in Song, which opens this Friday in New York.

Though born in Tibet, Ngawang had lived in exile with his mother since the age of two. While he had few memories of his homeland, attending the Dalai Lama’s Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts instilled in Ngawang a passion for the traditional music of his country that would cost him his liberty. Though his mother strenuously advised against it, Ngawang fatefully returned to Tibet in hopes of documenting the traditional songs before they were completely lost to posterity.

In Lhasa, Ngawang discovered the unofficial Chinese prohibitions against Tibetan cultural, religious, and linguistic identity had largely succeeded. However, like a Tibetan Alan Lomax, he found people in the provinces, usually the older generations, who were willing to be filmed as they sang and played the music of their ancestors. And then a funny thing happened on the road to Dawa.

In Lhasa, Ngawang discovered the unofficial Chinese prohibitions against Tibetan cultural, religious, and linguistic identity had largely succeeded. However, like a Tibetan Alan Lomax, he found people in the provinces, usually the older generations, who were willing to be filmed as they sang and played the music of their ancestors. And then a funny thing happened on the road to Dawa.

Suddenly, Ngawang was arrested and his film was confiscated. For years he endured the abuse of a Communist prison, but he still persisted in learning and singing traditional Tibetan songs. Eventually, the Chinese government relented to the pressure of a remarkable international campaign spearheaded by Ngawang’s mother – releasing the filmmaker, who would finally finish a very different film from what he presumably envisioned.

Song is a remarkable documentary in many ways. It all too clearly illustrates the unpredictable nature of nonfiction filmmaking, as events take a dramatic turn Ngawang was surely hoping to avoid. The film also bears witness to the Communist government’s chilling campaign to obliterate one of the world’s oldest cultures. Particularly disturbing to Ngawang are the ostensive Tibetan cultural revues mounted by the Chinese government that feature plenty of party propaganda but no genuine Tibetan music. In Orwellian terms, they represent an effort to literally rewrite Tibetan culture.

Indeed, what starts as a reasonably interesting survey of Tibetan song becomes a riveting examination of the occupied nation. Ngawang and the other former Tibetan prisoners he interviews have important (and dramatic) stories to tell, many of which express the significance of song to their own cultural identity. One of the few legitimate examples of heroic filmmaking, Song deserves a wide audience. Highly recommended, it opens this Friday (9/24) in New York at the Cinema Village, and in subsequent weeks travels to art house cinemas nationwide.

Posted on September 23rd. 2010 at 9:11am.

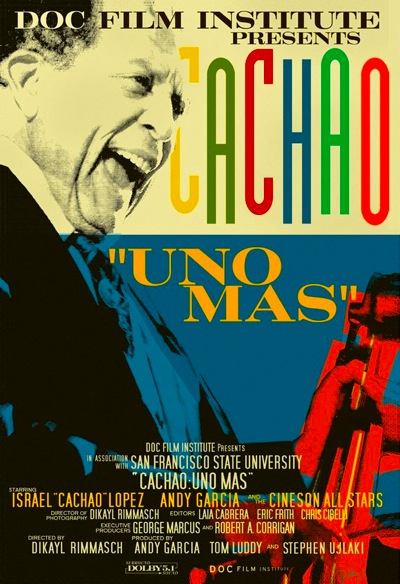

By Joe Bendel. He played for Presidents FDR and W. In between, he revolutionized Latin dance music, endured the pain of exile from his Cuban homeland, and enjoyed a late-career renaissance thanks in large measure to the efforts of musician-actor Andy Garcia. His name was Israel López, but most knew him simply as Cachao. His life and insistently danceable music are lovingly remembered in Dikayl Rimmasch’s Cachao: Uno Mas, co-produced by Garcia, which airs today as part of the current season of PBS’s American Masters.

A classically trained bassist, Cachao co-wrote Mambo #1 with his brother Orestes. Simply titled “Mambo,” it was the first of his signature danzóns (Cuban ballroom dances), featuring jazz like syncopation and an infectious rhythmic drive. Needless to say, the mambo was a hit—everywhere—spawning the global mambo craze. Yet, Cachao usually was not the one in the spotlight. Hip musicians certainly knew who he was though.

According to Cachao, he and his brother wrote 1,500 danzóns each. He also recorded his classic Descargas: Cuban Jam Sessions in Miniature, thoroughly blurring the distinctions between jazz and traditional Cuban musical forms. He even penned “Chanchullo,” the original melody that would become first Tito Puente’s and then Carlos Santana’s “Oye Como Va.” That Cachao never received proper credit or compensation for those monster hits still visibly rankles Garcia, but the zen-like master bassist was apparently unconcerned with such worldly matters.

According to Cachao, he and his brother wrote 1,500 danzóns each. He also recorded his classic Descargas: Cuban Jam Sessions in Miniature, thoroughly blurring the distinctions between jazz and traditional Cuban musical forms. He even penned “Chanchullo,” the original melody that would become first Tito Puente’s and then Carlos Santana’s “Oye Como Va.” That Cachao never received proper credit or compensation for those monster hits still visibly rankles Garcia, but the zen-like master bassist was apparently unconcerned with such worldly matters.

Unfortunately, worldly events would intrude into Cachao’s musical life. Though he initially supported the revolution against Battista, Cachao (like Garcia’s parents) chose the pain of exile as the oppressive nature of the Castro regime became painfully apparent. As the American Master himself explains: “Over there they say, ‘No, because of Fidel . . .’ and that’s it. Everyone is listening to you to hear what you say. If they don’t like it, you’re asking for trouble.”

Though Cachao passed away in early 2008, he was playing strong up until his final bar. Wisely, Uno Mas showcases his musical fire, fitting its profile segments around a scorching hot 2005 concert in San Francisco. Cachao swings like mad with an all-star ensemble including Garcia on bongos, John Santos on congas, Justo Almario on saxophone, and Federico Britos on violin (at one point engaging in some tasty call-and-response with the leader).

Utilizing nine cameras, Rimmasch shot some of the best live concert footage you are ever likely to see on television. He beautifully captures the unspoken back-and-forth between musicians, which probably gives a better sense of Cachao the man than any of the interview segments. Indeed, the music is so good, Uno Mas is probably destined to become a staple of PBS pledge break programming for years to come. While he does not perform in the film, trumpeter and Cuban defector Arturo Sandoval (played by Garcia in the under-appreciated HBO film For Love or Country) also adds some entertainingly animated musical commentary.

Cachao led a dramatic life and left behind an impressive body of absolutely joyous music. Like many Cuban exiles, he became a loyal patriot of two countries, making him a perfect subject for American Masters. Sometimes touching, but ultimately a blast of invigorating music, Uno Mas airs today (9/20) on PBS outlets nationwide.

Posted on September 20th, 2010 at 9:11am.