By Joe Bendel. Dr. Gene Sharp has been vilified by Hugo Chavez, the Iranian government, and bizarrely, the Occupy Oakland blog. Whatever such a man has to say is worth listening to, unless of course you are trying to protect the ruling party. In contrast, Dr. Sharp always sides with the revolutionaries, but advocates strictly nonviolent tactics. Journalist-filmmaker Ruaridh Arrow, who reported from Tahrir Square for the BBC, profiles Sharp and documents the applications of his work in How to Start a Revolution, which opens this Friday in Brooklyn at the ReRun Gastropub theater.

Dr. Sharp literally wrote the book on nonviolent revolution. It is called From Dictatorship to Democracy and it is available as a free download from the Albert Einstein Institute he heads. If you ever wondered why so many protests around the globe have signs written in English, it is because Dr. Sharp recommends it. He has a lot of general tactical advice, but eschewing violence is the essential point.

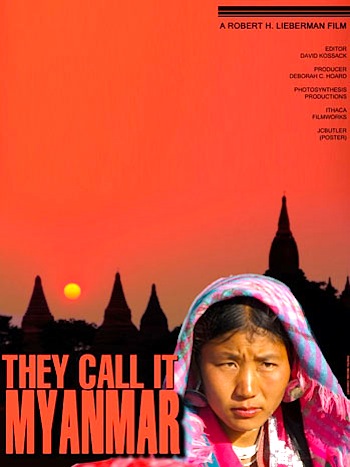

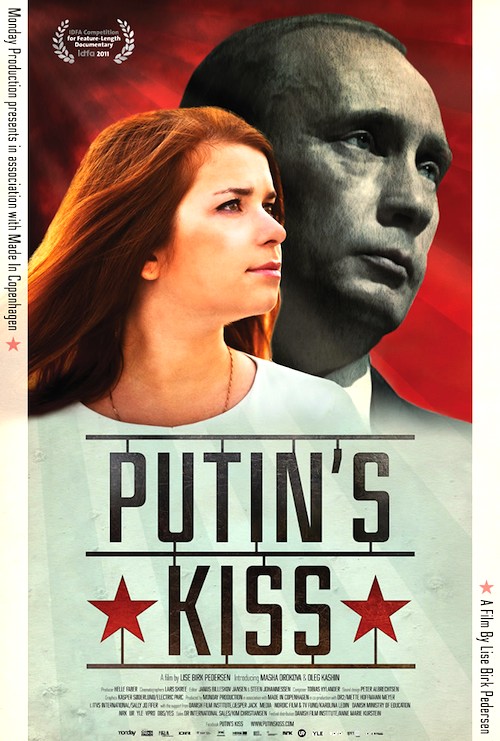

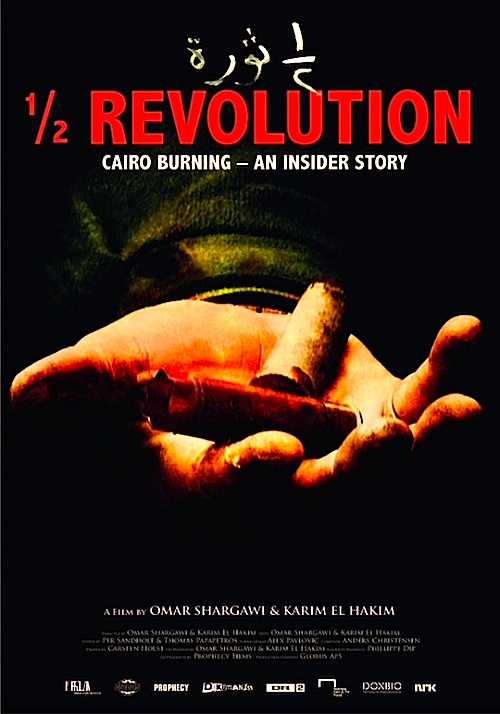

Nonviolence might sound hippy-dippy, but Dr. Sharp comes across as a rather down-to-earth nonpartisan scholar. He has just as readily advised democracy advocates struggling under leftist dictatorships – such as in Venezuela, Burma, Georgia, and Ukraine – as regimes considered friendly to American interests, like Mubarak’s Egypt. Despite the canard that he is a CIA puppet, his independence seems pretty evident, based on the Egyptian and Syrian activists who pay homage to Sharp in the Institute’s shoebox offices.

Arrow lucidly lays out Dr. Sharp’s principles and how various democracy movements have put them into practice. However, the results seem like more of a mixed bag than he would like to admit. In fact, Dr. Sharp’s celebrated volume was originally written for the Burmese, who have yet to shake off their military oligarchy, despite the enormous personal price nonviolently born by Aung San Suu Kyi. While applauding their courage, Dr. Sharp also argues the Tiananmen Square protests lacked proper planning and direction. They certainly were not able to co-opt the police and military, which is a crucial step in his playbook. As for Egypt, the jury is still out, but they seem to have traded a corruptocracy for military rule (if they are lucky, that is).

Probably the strongest material in Arrow’s film logically involves the greatest success: Serbia’s ouster of Slobodan Milošević. Trained in Dr. Sharp’s methods by his unlikely protégé, retired Col. Bob Helvey (who is as colorful an interview subject as ever there was), the opposition youth movement Otpor did everything right. It is a fascinating and inspiring story that remains woefully under-reported in this country.

HTSAR to will not spur wholesale conversions to pacifism. However, it will likely challenge and broaden the way people think about the continuing struggle for freedom and constitutional democracy around the world. Indeed, it is rare that a film offers so much to engage with. Unusually provocative and intellectually rigorous, HTSAR is (surprisingly) recommended quite keenly when it opens this Friday (2/24) at the ReRun Gastropub Theater.

GRADE: B+

Posted on February 24th, 2012 at 3:30pm.