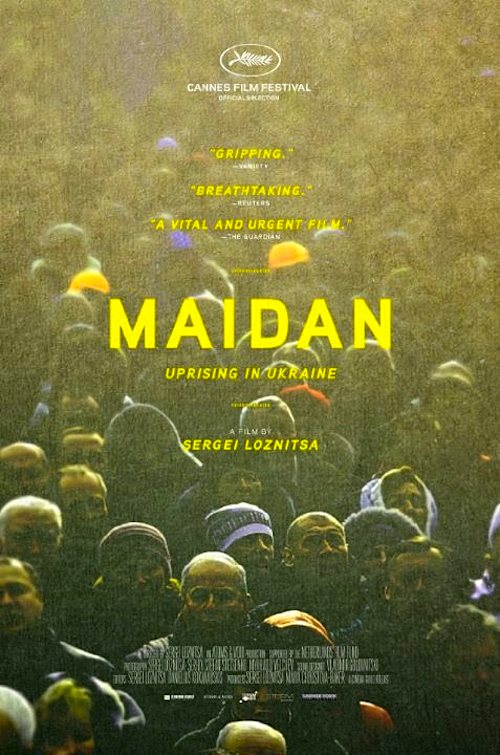

By Joe Bendel. The opening lyrics of the Ukrainian National Anthem make a fitting commencement for any film on the Euromaidan demonstrations and the subsequent Russian aggression: “Ukraine’s glory has not yet perished, nor has her freedom. Upon us fellow patriots, fate shall smile once more.” Let’s be frank, most of the media now considers Ukraine’s freedom a lost cause and the lame duck administration no longer has anything to say on the issue. Yet, when the Ukrainians unite in common purpose, they are a resilient force. Sergei Loznitsa captures his countrymen’s collective spirit in the direct cinema documentary Maidan, which opens this Friday in New York.

Kiev’s central city square is currently known as Maidan Nezalezhnosti, or Independence Square. It was previously known as Soviet Square, Kalinin Square (in honor of Stalin loyalist Mikhail Kalinin), and the Square of the October Revolution—and it might be so renamed again if deposed President Viktor Yanukovych and his Russian masters have their way. In late 2013, outraged Ukrainians took to the square, protesting Yanukovych’s decision to reject an association agreement with the EU, in accordance with Moscow’s wishes. Protests did indeed erupt in Maidan, the scene of many Orange Revolution demonstrations following Yanukovych’s suspect election in 2004, but it was far from the “pogrom” Putin suggested. Loznitsa has the footage to prove it.

In a way, it is too bad the Euromaidan movement advocates freedom and closer ties with the west, because Loznitsa’s documentary could have been the greatest socialist film ever made. Arguably, no other film so powerfully conveys the spirit of collective action and a sense of individuals dedicating themselves to a larger cause. There are many long takes and wide angle crowd shots, but Loznitsa and his fellow cameraman Serhiy Stefan Stetsenko capture the tenor of the time quite viscerally.

Loznitsa never focuses on representative POV figures, maintaining a macro perspective throughout. Nevertheless, we can easily observe the trends and magnitude of the situation from his vantage points. At first, there is very much a sense that things will change, much as it did in 2004. We see the volunteers making sandwiches and distributing tea to regular Sunday night demonstrators. A gullible media largely accepted Putin’s smears at face value, but it is hard to imagine a neo-fascist movement would dispatch four volunteers to make sure nobody slipped on a spot of spilled water in the lobby.

Loznitsa never focuses on representative POV figures, maintaining a macro perspective throughout. Nevertheless, we can easily observe the trends and magnitude of the situation from his vantage points. At first, there is very much a sense that things will change, much as it did in 2004. We see the volunteers making sandwiches and distributing tea to regular Sunday night demonstrators. A gullible media largely accepted Putin’s smears at face value, but it is hard to imagine a neo-fascist movement would dispatch four volunteers to make sure nobody slipped on a spot of spilled water in the lobby.

Tragically, Yanukovych would unleash the Interior Ministry’s Berkut forces in January. At this point the audience can clearly see how unscripted Loznitsa’s film truly was, as either the director or his co-cinematographer is caught in a tear gas attack. They maintain the same long fixed approach, but the pleas for medical personnel to come to the stage area to treat the collected wounded speaks volumes about the old regime. Not to be spoilery (unless you work at a major network, you should already know this ends rather badly), but Loznitsa concludes the film with a funeral for two fallen activists, which is absolutely emotionally devastating, even without a personal entry-point character to concentrate on.

Still, the individual stories of Maidan supporters desperately need to be heard, which is why Dmitriy Khavin’s Quiet in Odessa is such a timely and valuable film. Since there is almost no supplemental context in Loznitsa’s Maidan it is best seen in conjunction with a film like Khavin’s. However, it has the virtue of presenting events as they happened and allowing the audience to draw their own conclusions. Highly recommended for anyone seeking an immersive understanding of Ukraine’s Euromaidan movement, Loznitsa’s Maidan opens this Friday (12/12) in New York, at the Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center.

(The international film community should also note that Ukrainian filmmaker Oleg Sentsov is still being held incommunicado in Russia, on trumped-up terrorism charges, awaiting his day in kangaroo court. Along with Loznitsa’s Maidan and Khavin’s Odessa, film programmers ought to consider scheduling Sentsov’s politically neutral Gaamer to raise awareness for his plight.)

LFM GRADE: A-

Posted on December 9th, 2014 at 8:23pm.