By Joe Bendel. You can pretty much count on one finger the jazz musicians who have received Papal commissions. Mary Lou Williams will always be remembered for excelling as a musician-arranger-composer at a time when the music industry was ridiculously male-dominated. Yet, by reconciling and combining jazz with her Catholic faith, Williams shattered just as many musical preconceptions. Williams’ life and music are surveyed in Carol Bash’s Mary Lou Williams: The Lady Who Swings the Band, which premieres on many PBS stations this week.

Williams was a child prodigy born to play the piano, but she first started to make a name for herself in Kansas City, at the height of the town’s hipness. Most musicians were loath to play with women, but her husband, alto and baritone player John O. Williams, knew she could swing. When his boss, territory bandleader Andy Kirk, found himself caught without a piano player, he reluctantly called her in to sub. Needless to say, she basically made Andy Kirk and the Clouds of Joy. Naturally, he resented her for it, but the producers were adamant—no Williams, no contract.

Eventually, Williams would separate from both Kirk and her husband, striking out on her own. Despite her talent and reputation, she would experience all the ups and downs of the jazz musician’s life, except it was always even more challenging for Williams—until she heard what can be rightly described as her calling. Finding spiritual renewal in the Catholic Church, Williams was encouraged to use her musical gifts, but in a way that expressed her deepening faith.

It is great to see Bash fully explore the significance and influence of Williams’ sacred music. She also gives the jazz legend her due as an entrepreneur – self-producing her releases on her own Mary label, long before that became the industry norm. However, the film leaves some unanswered questions regarding her relationship with John O. According to his obit, he also played with the Cootie Williams band and co-wrote “Froggy Bottom,” which suggests he might be one of those unfairly overlooked kind of guys.

Of course, the music is the most important thing in Lady Who Swings. Bash incorporates some all-star performances, appropriately including Geri Allen, who played the Mary Lou Williams figure in Robert Altman’s unfairly panned Kansas City. Wycliffe Gordon also leads a big band and Carmen Lundy lends her vocal chops and elegant presence, but Bash cuts off them off before they really get started. That is a shame, because just about all of us interested in Williams will want to hear their take on her music. Maybe the concert interludes are allowed to go on longer in a more extensive festival cut.

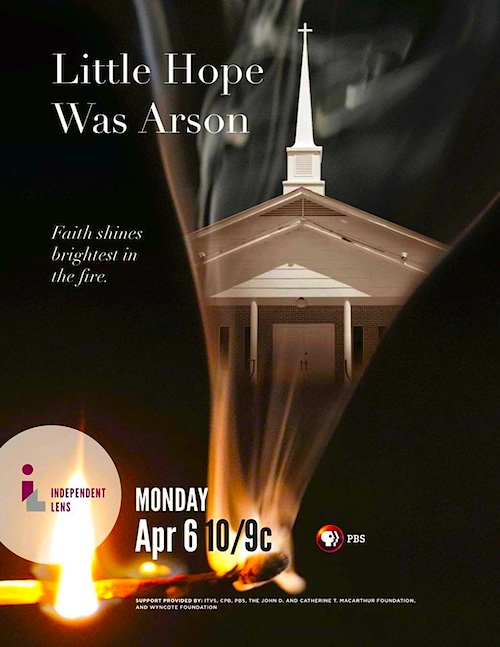

Indeed, fifty-four minutes on Mary Lou Williams is certainly economical, but it only scratches the surface and whets the appetite. Nevertheless, Bash makes sure viewers leave with the right take-aways. If you still don’t understand Williams was Catholic who could still swing hard after watching her film, you have serious retention issues. Brisk, informative, and respectful of Williams’ Catholicism, Mary Lou Williams: the Lady Who Swings the Band will leave audiences wanting more, but what we have is still definitely worth seeing. Highly recommended, it airs Monday night (4/13) in LA and Wednesday night (4/15) in San Francisco, with more airdates to come across the country, so check those local listings.

LFM GRADE: B+

Posted on April 13th, 2015 at 3:56pm.