By Joe Bendel. Sophie Tucker once called up JFK in the Oval Office, was immediately connected, and successful convinced him to veto pending stock dividend taxation legislation. If that does not duly impress you, keep in mind she also sang—for decades, as one of the top speakeasy and night club attractions in the country. Filmmaker William Gazecki and producer-Tucker biographers Susan & Lloyd Ecker chronicle her bawdy, trailblazing career in The Outrageous Sophie Tucker, which opens this Friday in New York.

Tucker’s career spanned six decades and just about every Twentieth Century form of media. She was tough and shrewd, but also loyal and generous. She made her debut in the Ziegfeld Follies at twenty-two, but she was too much of a smashing success, at least from the star diva’s vantage point. Before Mae West, she became a sensation suggestively interpreting double entendre-laden lyrics. She was still a household name well into the 1960s, thanks in part to her old crony, Ed Sullivan, but she has largely slipped into the memory hole of a collective cultural memory that barely reaches back to Madonna.

Fortunately, this is where the Eckers come in, burnishing her legacy and promoting awareness. For their books, website, and work on this film, the Eckers were invaluably assisted by the exhaustive multi-volume scrapbooks Tucker maintained, recording her career almost day-for-day. They also serve as time-capsules, capturing the state of show business from 1907 to 1964.

Tucker had such a strong sense of syncopation and a flair for giving lyrics her own unique twist, she could have easily billed herself as a jazz artist, if she had wanted to be paid less. Yet, what is most striking is how far ahead of the curve she was when it came fan outreach. She probably had a MySpace page ready to go, just waiting for the internet to get created.

Tucker’s music and her tart-tongued Horatio Alger story are wildly entertaining. However, despite some creative use of graphics, Outrageous does not look very cinematic. In fact, many of the talking head segments (featuring 1st class artists like Tony Bennett, Carol Channing, and Michael Feinstein) feel very TV-ish. The Eckers (especially Lloyd) are clearly determined to explain just how much Tucker means to them, whether we are interested or not. Nevertheless, it must be granted, they have become the definitive authorities on all things Tucker.

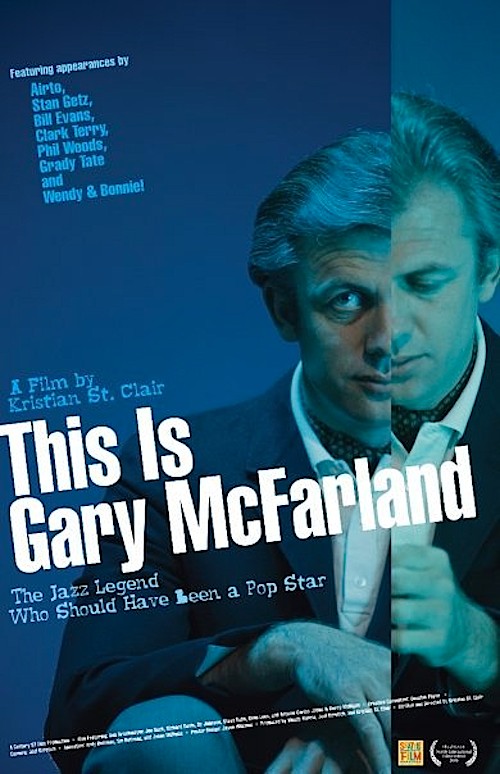

Even if it is not as aesthetically polished as top-notch music docs, like This is Gary McFarland and Searching for Sugar Man, Outrageous does right by its subject and star. Gazecki and company maintain a high energy level and display a deep understanding of Tucker’s many complicated relationships. Recommended for fans of Tucker and the Great American Songbook, The Outrageous Sophie Tucker opens this Friday (7/24) in New York, at the Cinema Village.

LFM GRADE: B

Posted on July 24th, 2015 at 12:43pm.