By David Ross. Constructing literature courses is relatively easy, because literary history is so coherent and clearly marked – its nodes are so inarguable. You can no more bypass Austen or Dickens in a course on the British novel than you can bypass London on a trip to the UK.

Film, which I will teach for the first time in the Spring, is different. Unlike poetry or even the novel, film is a living form. It continues to unfold and redefine itself, and it forces one constantly to reconsider what seemed fixed. Bergman, for example, may be the greatest director of all time, but his kind of filmmaking – let’s call it filmed theater – seems everyday less relevant, while Godard, who cannot compare as a directorial talent or philosopher, seems to have put his finger on the future. Whom to prefer? Did Mssrs. Lucas and Spielberg reinvent American mythmaking (Mr. Apuzzo’s view, if I’ve understood him correctly these twenty years), or did they infantilize our popular entertainment (my view)?

And what of those beloved heirlooms of Hollywood’s golden age that are neither entirely art nor merely entertainment, and that, in any case, nobody younger than fifty has particularly bothered to see? Are they historical artifacts, national treasures, charming baubles, or inadvertent masterpieces? In teaching them, do we chronicle the American Spirit or do we dumb down the curriculum? In general, is film high art or popular art – a belated expression of the old Renaissance aspiration, or a symptom of capitalist energy and mass consumption?

Designing my course – “Film and Society” – was a two-tablet headache due to the unanswerable questions above. I was not sure what a film course should be, because I have only a confused idea what film is and what it’s for. In the end, I treated film as high art on the model of literature, not because this makes the most or best sense of film as a medium, but because students have so little exposure to the old Renaissance aspiration, and because no opportunity to complicate their sense of the sufficiency of Avatar and Twilight can be passed up. At the same time, one must make certain concessions (Miyazaki for example) in order to avoid civil unrest and student evaluations drenched in one’s own blood (see here).

Not long ago, I described Into Great Silence (2005), a documentary about life in a Carthusian monastery in the mountains of France, as “one of the more difficult and beautiful films ever made, and perhaps film’s most sincere and respectful attempt to portray the life of religious devotion.” It occurs to me that Ordet (1955), even more so, knows how to bend its Medieval knees (to borrow a phrase from Yeats).

I would have liked to teach the Tykwer-directed, Kieslowski-penned Heaven (2002) in conjunction with A Serious Man (2009). The films are fascinatingly obverse. The former concerns a seemingly compromised woman who experiences a mysterious and miraculous beatitude; the latter, a seemingly righteous man who suffers endless punishment.

My syllabus is still germinal. I would, of course, appreciate any advice. One thing to keep in mind is that the course is already busting a seam. Adding necessarily entails subtracting.

The Palace of Art

- The Mystery of Picasso (1956, Henri-Georges Clouzot)

- 8 1/2 (1963, Federico Fellini)

- Russian Ark (2002, Aleksandr Sokurov)

- Hero (2003, Zhang Yimou)

Masculin/Feminin

- A Woman is a Woman (1961, Jean Luc Godard)

- Woman of the Dunes (1964, Hiroshi Teshigahara)

- My Night at Maud’s (1969, Eric Rohmer)

- Annie Hall (1977, Woody Allen)

God in the Dock

- Ordet (1955, Carl Theodor Dreyer)

- Aguirre: The Wrath of God (1972, Werner Herzog)

- Fanny and Alexander (1983, Ingmar Bergman)

- A Serious Man (2009, Coen Brothers)

The Smell of Napalm in the Morning

- The Grand Illusion (1937, Jean Renoir)

- The Battle of Algiers (1965, Gillo Pontecorvo)

- Shame (1968, Ingmar Bergman)

- Apocalypse Now (1979, Francis Ford Coppola)

Earth Abides

- Derzu Uzala (1975, Akira Kurosawa)

- Stalker (1979, Andrei Tarkovsky)

- My Neighbor Totoro (1988, Hayao Miyazaki)

- Maboroshi No Hikari (1995, Hirokazu Koreeda)

Utopias and Dystopias

- Smiles of a Summer Evening (1955, Ingmar Bergman)

- Raise the Red Lantern (1991, Zhang Yimou)

- Koyaanisqatsi (1982, Godfrey Reggio)

- The Lives of Others (2007, Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck)

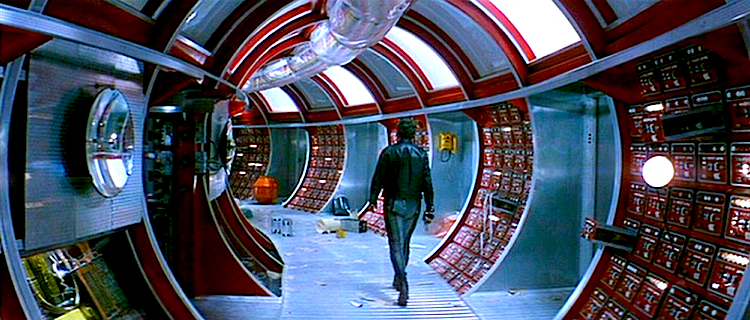

Brave New World

- 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968, Stanley Kubrick)

- Solaris (1972, Andrei Tarkovsky)

- Cache (2005, Michael Haneke)

- Encounters at the End of the World (Werner Herzog, 2007)

Other films I seriously – yearningly in some cases – considered, but in the end could find no place for:

- La Ronde (1950, Max Ophuls)

- Diary of a Country Priest (1950, Robert Bresson)

- Secrets of Women (1952, Ingmar Bergman)

- The Earrings of Madam de … (1953, Max Ophuls)

- Cleo from 5 to 7 (1961, Agnes Varda)

- Woman of the Dunes (Hiroshi Teshigahara, 1964)

- A Clockwork Orange (1971, Stanley Kubrick)

- The Sorrow and the Pity (1972, Marcel Ophuls)

- Yellow Earth (Chen Kaige, 1984)

- Wings of Desire (1988, Wim Wenders)

- Lessons in Darkness (1992, Werner Herzog)

- After Life (1999, Hirokazu Koreeda)

- Heaven (2002, Tom Tykwer)

- Grizzly Man (2005, Werner Herzog)

- 24 City (2008, Zhang Ke Jia)

Posted on September 14th, 2010 at 11:22am.