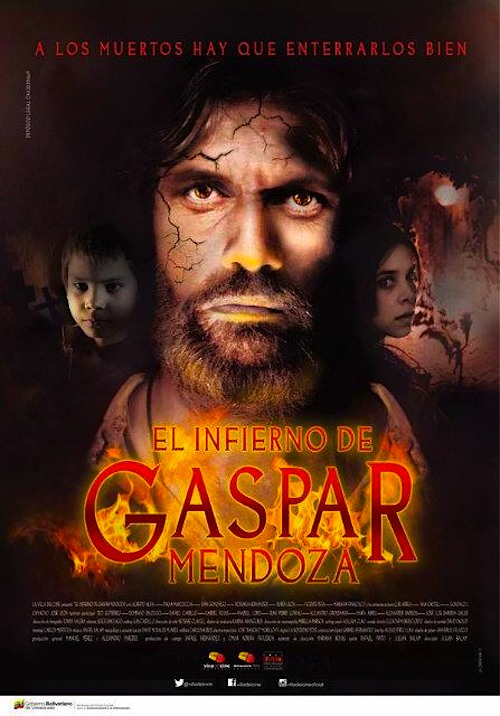

By Joe Bendel. Captain Gaspar Mendoza was on the winning side of the revolution. He saw plenty of war, but his conscience does not trouble him, at least not very much. However, he seems highly dependent on a talismanic charm. It does not seem to work so well judging from his daughter’s ill health and the severe draught plaguing the land. Yet, that is nothing compared to the distress headed his way in Julián Balam’s Gaspar Mendoza’s Hell, which screens as part of the upcoming Venezuelan Film Festival in New York.

By Joe Bendel. Captain Gaspar Mendoza was on the winning side of the revolution. He saw plenty of war, but his conscience does not trouble him, at least not very much. However, he seems highly dependent on a talismanic charm. It does not seem to work so well judging from his daughter’s ill health and the severe draught plaguing the land. Yet, that is nothing compared to the distress headed his way in Julián Balam’s Gaspar Mendoza’s Hell, which screens as part of the upcoming Venezuelan Film Festival in New York.

The Captain’s daughter, María Eugenia, has not had a sound night’s sleep in months. Fearing for her sanity, her mother insists on her long-deferred baptism, to which Mendoza reluctantly agrees. Rather ominously, the ceremony is interrupted by the discovery of a young thief. He is a surly looking waif, but María Eugenia takes a shine to him anyway. Mendoza’s old lieutenant wants to deal with him in the age old manner, but the Captain humors his daughter. Supposedly, the boy will be put to work, but he acts like he has the run of the place.

He will indeed be a destabilizing influence on the estate, particularly with María Eugenia. She starts acting out and asking awkward questions about the past, including the exploits of the Keyser Söze figure, whose grave mysteriously appeared in the parish cemetery—or so the legend goes.

If you are not crazy about kids you will actively dislike “El Niño,” played with a defiant lack of subtlety by the young thesp. He is just a little Hellion, even if you can guess his grisly backstory. No question about it, Mendoza’s right-hand man had the right idea. Frankly, it is hard to accept María Eugenia’s affection for him, even if we make allowances for supernatural forces working upon her.

On the other hand, Alberto Alifa’s Mendoza is a grandly tragic figure. He projects the right military bearing, even when his world is collapsing around him. Balam and the design team also crank up the gothic atmosphere, centering the drama with a very dark, humid sense of place. Even before the kid starts making trouble, we get seriously bad vibes, as if the sterile soil and María Eugenia’s feverish dreams are a sign of Biblical judgement.

Cinematographer Tony Valera’s work is suitably creepy and evocative. It is a well-constructed period drama, María Fernada Martinez’s script holds few surprises. Still, for Nineteenth Century supernatural morality play shot on a shoestring budget, it looks surprisingly credible. Curious genre fans will find Alifa’s work and the general eeriness are worth checking out when Gaspar Mendoza’s Hell screens this Friday (9/25) at the Village East, as part of the Venezuelan Film Festival in New York.

LFM GRADE: B-

Posted on September 23rd, 2015 at 11:33pm.