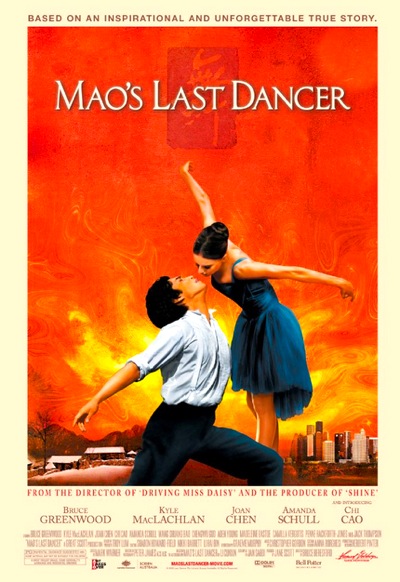

By Joe Bendel. For fifty-plus years, Mainland China’s Communist government has experienced bitter factional rivalries and instituted enormously destructive campaigns for ideological purity. While the pendulum has swung back and forth from relative stability to institutionalized insanity, it has remained an authoritarian state where artistic freedom is simply impossible. That is why twenty year-old ballet dancer Li Cunxin defected to America in the early 1980’s. It was a bold decision that would define Li’s bestselling memoir and Oscar-nominated director Bruce Beresford’s subsequent big-screen adaptation, Mao’s Last Dancer, which opens this Friday (8/20) in select theaters nationwide.

As a young boy, Li was slight but flexible as enough to be accepted at Madame Mao’s ballet academy. Diligently training to build his strength, his natural talent blossomed -even in the didactic productions foisted on the academy by their ideologue patron.

As a young boy, Li was slight but flexible as enough to be accepted at Madame Mao’s ballet academy. Diligently training to build his strength, his natural talent blossomed -even in the didactic productions foisted on the academy by their ideologue patron.

Eventually Li was entrusted to study with the Houston Ballet as part of a cultural exchange program. Primed to expect unspeakable misery, Li slowly discovers America is not as he was led to believe. Acclimating to the new environment, he actually finds he dances better in the land of class enemies because he “feels freer.” He also falls in love with Elizabeth Mackey, an aspiring dancer. Then his life really starts to change.

Li indeed decides to defect, news the Chinese government does not happily receive when he ill-advisedly delivers it in-person. In fact, they forcibly detain him in the Consulate, with the intention of whisking him out of the country against his will. However, Li’s friends refuse to leave quietly (fortunately Texans can be an unruly lot), precipitating an international incident.

Dancer is a truly inspiring crowd-pleaser of a film, but it is not an overly-sanitized or conveniently simplistic reduction of a complex, real life story. In fact, the guilt-wracked Li, fearing dreadful repercussions for his family, frequently quarrels with Mackey, eventually even divorcing her. Yet, as a result, Li emerges as a flesh-and-blood human being. We can also forgive the film for indulging in its manipulative coda, having more or less earned its triumphant freeze frame.

As wildly improbable as it might sound, much of Dancer was shot on-location in China. Reportedly, once shooting was underway, the authorities began demanding changes to the script, but to his credit, Beresford rebuffed them. As a result, there are indeed scenes of Madame Mao (who remains an official non-person in China), played by a truly eerie dead-ringer for the Gang of Four leader. We also watch as Li’s mentor at the academy is purged for perceived ideological offenses, such as teaching the techniques of counter-revolutionary defectors like Nureyev and Baryshnikov. (Granted, the film also seems to imply contemporary China may be loosening up, at least to an extent.)

Perhaps Dancer’s greatest challenge was casting credible dancers for its key leads roles. Again, fortune smiled with the discovery of the considerable acting chops of Chi Cao (currently Principal Dancer with the Birmingham Royal Ballet) and Chengwu Guo (a member of the Australian Ballet) as the adult and teen-aged Li, respectively. Both prove to be charismatic performers, with Chengwu making a surprisingly strong impression, even with his limited screen time. (Hopefully, they will both be allowed to return home, despite their participation in the film.)

Dancer also boasts two Twin Peaks alumns – including Kyle MacLachlan, making the most of a small supporting role as crafty immigration attorney Charles Foster. It is Joan Chen who really delivers the film’s emotional punch though, as Li’s spirited mother Niang. Even thoroughly glammed down for the role, she still remains a radiant beauty.

Dancer is a well-rounded, fully satisfying bio-picture. The product of Australian filmmakers, it refreshingly refrains from kneejerk political cheap shots, even implying then Vice President Bush played an important role securing Li’s freedom. It also vividly captures Li’s passion for dance, which is the fundamental cause of nearly every event that unfolds in the film. Emotionally engaging and politically astute, Dancer opens this Friday (8/20) in select theaters nationwide.

Posted on August 18th, 2010 at 11:58am.