[Note:This article contains SPOILERS. I love Leave Her to Heaven, but I was spoiled for one of its biggest scenes. Ideally you should watch it first, then come back and we’ll peel the face off the Technicolor mask.]

By Jennifer Baldwin. Is there a better movie about romantic obsession than Leave Her to Heaven? Is there another movie as disturbing and unflinching in its portrayal of a woman obsessed as this film, this nightmare vision in Technicolor? To see the film only once is to remember it forever. It’s no wonder, then, that I’ve been obsessed with Leave Her to Heaven for over a decade. It’s a movie not only about obsession, but one that invites obsession on the part of the audience. We are invited to obsess over the colors, the beauty, the horribly evil acts committed by Gene Tierney’s Elle Berent. That Ellen is a deadly enigma only makes it more fascinating to obsess over her.

I blame Martin Scorsese. One night, many years ago, I stumbled onto his documentary A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through American Movies playing on TCM. Three movie clips from the documentary stayed with me long past that night, haunting me, nagging at my mind: clips from Cat People, Scarlet Street, and Leave Her to Heaven. As time went by, it became a kind of quest to track these movies down. First came Cat People and I was spooked by the shadows and the dreaded suggestion of horror. Next came Scarlett Street and I was shocked by the brutal violence and even more brutal cynicism.

When I finally saw Leave Her to Heaven it was almost too overwhelming to describe. The colors, the murders, the pounding tympani, Gene Tierney’s eyes – all the lurid perversity of it burned forever into my brain. I loved it. It was the most delirious melodrama I had ever seen. It still is. It’s woman’s melodrama with a black soul. It pulls the mask back on the notion of romantic, all-consuming love and gives us the horror underneath. And yet, it is achingly beautiful to look at, the beauty and the horror intertwined so that it becomes more than just the story of a monstrous, murderous woman – it becomes a tragedy. Fitting that the title should be a line from Hamlet.

Leave Her to Heaven is essentially two things: Leon Shamroy’s color cinematography and Gene Tierney’s lead performance. Bringing these two essentials together, of course, is the underrated director, John M. Stahl. It is Stahl, in an act of alchemical wizardry, who is able to fuse Tierney’s subtle, disturbing performance with Shamroy’s wild, unrestrained use of Technicolor (all with a handy assist from the set design, art department, and costuming).

Stahl’s film is popular art at its best, a finely balanced creation that melds melodramatic, expressionist visuals with naturalistic, subdued, almost mannequin-like acting styles, so that the effect is a kind of hallucinatory hyper-reality that nevertheless remains remote and mysterious. We never quite know what to make of Ellen’s character.

Why does Ellen act the way she does? Why is her love so ruinously obsessive? Is she evil? Is she merely insane? Is it possible to feel sympathy for her even as she scares the hell out of us? What about her love? Was her love completely rotten and selfish to the core or was there some small piece of it that was true and human and only later became twisted?

Gene Tierney doesn’t get enough credit either as an actress or as a movie star. As far as Leave Her to Heaven is concerned, she is the whole movie. The film loses something – some spark, some energy – when her character dies and Tierney has left the screen. Only Vincent Price’s theatrical courtroom shouting saves the last quarter of the film from collapsing into anticlimax.

And lest anyone doubt Tierney’s performance or her star quality, answer this: what was 20th Century Fox’s highest grossing movie of the 1940s? Leave Her to Heaven. You don’t deliver the studio’s highest grossing picture of the decade if you’re not a star. And who was nominated for a Best Actress Oscar in 1945? Gene Tierney. It’s a shame that she is not more well known today.

Leon Shamroy’s cinematography won the Oscar that year, deservedly so. But it really should have been a double win for Shamroy and Tierney at the Academy Awards of 1945, because Shamroy’s cinematography is merely an extension of Tierney’s performance and vice versa. No one can fault the Academy for giving Joan Crawford an Oscar for Mildred Pierce, but I think in a perfect world it would have been Tierney.

I’m fascinated by the decision to shoot the film in color. Most color films in the mid 1940s were musicals or big budget Westerns. A melodrama like Leave Her to Heaven would ordinarily be a black and white affair. Except Leave Her to Heaven was based on a bestselling novel by Ben Ames Williams – a novel that was wildly popular with audiences, resulting in one of the most highly anticipated film adaptations of the day. It was the kind of prestige picture – and potential moneymaker – that could justify the extra cost to shoot in Technicolor.

What Stahl and Shamroy did with that color is nothing short of breathtaking – not just in the look of the color, but in the way color was used. I’m hard-pressed to think of another movie that depends so much on the use of color to affect mood, theme, and character. It’s been said that the color cinematography in Leave Her to Heaven is so powerful that it’s almost a character in its own right. I think a better way to put it is that the color cinematography isn’t a separate character so much as an extension of one character, the central character of the story: Gene Tierney’s Ellen Berent.

Gene Tierney was one of Hollywood’s greatest beauties, but one thing I’ve heard is that the camera didn’t quite capture how beautiful she was. Part of this had to do with the fact that she made a lot of black and white films and those films weren’t able to display one of her greatest features: her blue-green eyes.

No such problem in Leave Her to Heaven. In fact, the color scheme of the film – dominated by blues, greens, reds, and pinks (along with an eerie amber glow that hovers over most of the film) – is primarily dictated by Tierney’s appearance. Her blue-green eyes and striking red lipstick are used as a template to color almost every frame of the picture. Everywhere there is blue, green, and red. Just as Ellen promises Richard (Cornel Wilde) that she’ll never let him go, so too do Ellen’s “colors” never let the film go– they dominate to such a degree that her presence is felt in almost every frame, even when she’s not there. Continue reading Classic Movie Obsession: Leave Her to Heaven

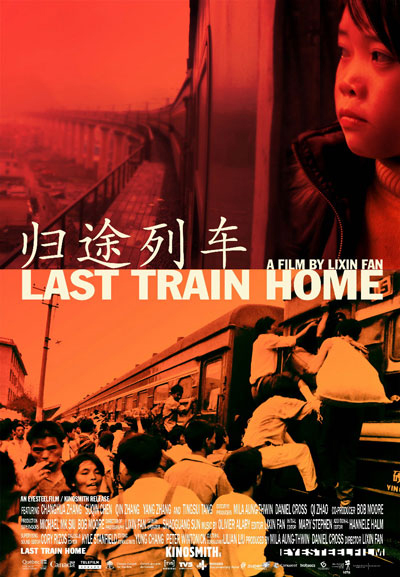

Zhang Changhua and Chen Suqin are second class citizens, veritable illegal aliens within their own countries. Under the government’s restrictive residency laws, they have few formal rights and no access to social services outside their home district. Yet, they have had little choice but to seek work in China’s teeming urban centers. As a result, they have rarely seen the pre-teen daughter and young son they left to be raised by their grandmother.

Zhang Changhua and Chen Suqin are second class citizens, veritable illegal aliens within their own countries. Under the government’s restrictive residency laws, they have few formal rights and no access to social services outside their home district. Yet, they have had little choice but to seek work in China’s teeming urban centers. As a result, they have rarely seen the pre-teen daughter and young son they left to be raised by their grandmother.