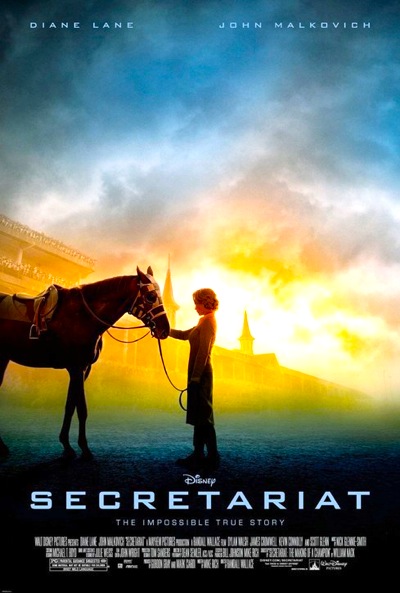

By Jason Apuzzo. When I was in high school, some of my football buddies and I would trek over to Hollywood Park here in Los Angeles on weekends to watch horse races. My friends went to gamble; I never bet a dime. I went for the spectacle, and most of all for the supernal beauty and intensity of the horses themselves. There was something so pure and lovely about them; at the same time, look into the eyes of any racehorse and you will see a kind of wild, daemonic energy that you don’t always see in other animals – something both divine and furious that propels them down the track. And although I haven’t really followed horse racing or horses in a long time, I was reminded of all that watching Randall Wallace’s superb new film, Secretariat – one of the better live-action films I’ve seen from Disney in years.

By Jason Apuzzo. When I was in high school, some of my football buddies and I would trek over to Hollywood Park here in Los Angeles on weekends to watch horse races. My friends went to gamble; I never bet a dime. I went for the spectacle, and most of all for the supernal beauty and intensity of the horses themselves. There was something so pure and lovely about them; at the same time, look into the eyes of any racehorse and you will see a kind of wild, daemonic energy that you don’t always see in other animals – something both divine and furious that propels them down the track. And although I haven’t really followed horse racing or horses in a long time, I was reminded of all that watching Randall Wallace’s superb new film, Secretariat – one of the better live-action films I’ve seen from Disney in years.

Truth be told, Secretariat really isn’t so much about the legendary race horse that electrified the sports world in 1973. Wallace and screenwriter Mike Rich realized, smartly, that the phenomenal thoroughbred (nicknamed ‘Big Red’) who still owns the track records at two of the three Triple Crown races – the Kentucky Derby, and the Belmont Stakes – is too legendary, too awesome a figure to center the story around. Almost forty years after the horse’s greatest triumphs, rooting for Secretariat is a bit like rooting for a hurricane – you already know the outcome. And so Wallace and Rich smartly shifted the story of Secretariat to where it quite clearly needed to be: with the horse’s fiesty, headstrong owner Penny Chenery, played in this film with style and intensity by Diane Lane. Secretariat is essentially Penny Chenery’s story – and, as we learn in ways both subtle and overt, her story is really America’s.

As Secretariat opens, we’re introduced to housewife Penny Chenery and her pleasant, unassuming family in what appears to be a middle-class, WASPish burg of Colorado. A sudden tragedy in the family sends her to Virginia, where she’s forced to take over the family horse ranch. Chenery does a little research, and discovers that the lineage of one of the foals in her care may portend something special – although the horse racing professionals around her, as well as her family, all doubt it. At a coin toss between Chenery and legendary racing owner Ogden Phipps over Secretariat’s fate, Phipps wins the coin toss – and picks another horse for himself, leaving young Secretariat to a suddenly very happy Chenery. And history, as they say, was made.

Chenery puts Secretariat in the hands of French-Canadian trainer Lucien Laurin, played here with warmth and (predictably) eccentric humor by John Malkovich. It’s nice to see Malkovich play something other than a freak, frankly – I wasn’t sure he could still do it. His performance brings a dash of life and sophistication to the proceedings. We follow Laurin and Chenery as they train the horse and prep it for its first big race at the Aqueduct Racetrack in New York. I don’t want to give anything away here, but let’s just say that Secretariat’s first big race doesn’t exactly go as planned; both Laurin and Chenery realize that they’ve been following the wrong strategy – they’ve been too cautious – with their curiously slow-starting, almost lazy horse.

Secretariat, you see, is a bit of a show-off, who likes to start his races slow – at a casual pace – typically beginning each race at the back of the pack … only to come charging in late and finish strong. This, we learn, is part of the dual miracle that Secretariat represented: not only did the horse shatter records, but he typically ran like he was asleep for the first half of any race. And, indeed, even when he finished races in record time he was typically still accelerating at the finish. Another way of putting it is that the horse Secretariat was a bit of a gambler, much like his owner – and difficult to train.

Secretariat’s ability to live up to his full potential becomes a huge issue for Penny Chenery because when her long-ill father (played by Scott Glenn) finally passes away, the estate taxes on his ranch amount to $7 million – and Chenery is suddenly in the awful position of having to either sell her beloved Secretariat, or gamble everything her family owns on the horse. In essence, the horse has to win The Triple Crown – or at a minimum The Kentucky Derby – or her family could be ruined.

The easy decision for Penny Chenery at this point would have been to sell the horse. It’s not the choice she makes, however. And let’s pause for a moment and dwell on this point.

As some of you may be aware, Secretariat has improbably become a ‘controversial’ film in recent days – largely due to the fact that Salon’s Andrew O’Hehir (hostile over the fact that Randall Wallace has been promoting Secretariat to Christian audiences) went off his meds recently and called the film (among other things) “a work of creepy, half-hilarious master-race propaganda almost worthy of Leni Riefenstahl … a quasi-inspirational fantasia of American whiteness and power.”

O’Hehir’s toxic and abusive ramblings aside, it doesn’t surprise me that progressive critics of his ilk would react badly to Secretariat, as the film’s real purpose – it’s ‘agenda,’ as we say nowadays – seems to be the valorizing of a certain kind of stubborn, resourceful, tight-lipped Yankee/WASP woman (the type of woman Katherine Hepburn and Joan Crawford and Bette Davis built their careers on) that appears to have faded away in our current age of ‘resentment,’ as Harold Bloom likes to call it. If Secretariat is anything, it’s a love letter to that particular kind of woman from America’s past – and, hopefully, America’s future.

Our ‘resentful,’ politicized era – the era of Lady Gaga and Lisbeth Salander – no longer seems interested in women like Penny Chenery, i.e. classy, stiff-upper-lip-type dames in smart business suits with perfectly coiffed hair who get their way through moxie and determination. For various reasons we’ve told ourselves that we don’t need these kind of women anymore, especially on-screen, because we’ve ‘advanced’ into a Brave New World where women get their way through some combination of: a) harpie-like political agitation; b) screwing men blind, after they’re already pumped full of Viagra; c) narcissistic fugue-states, fueled by Facebook and reality TV, or; d) unloading a full machine gun clip at people they don’t like (Angelina Jolie/Milla Jovovitch/Kate Beckinsale, etc.).

It never seems to occur to people like O’Hehir – and there are a lot of them, particularly in the entertainment industry – that none of these represent valid options for most women, even if they’re sometimes fun to watch on-screen. Secretariat’s Penny Chenery is that old-school type of woman who dominated Hollywood cinema in the 1940s – and American life in the 1950s – who gets her way in life because she’s got steel in her spine, and is willing to take enormous risks even when the pusillanimous men around her (and there are a lot of them in this film) tell her not to.

So back to the film. As the stakes get higher for Chenery, people start to fall away. One of her daughters – the very blonde and very perky AJ Michalka – grows distant and starts to dabble in left-wing activism (admittedly, some of the scenes with Michalka are obviously played for laughs). More serious is that Chenery’s brother – and even her husband – abandon her at one point, consigning her to take all the financial risks associated with backing the horse. Ouch. [Why Chenery lets these stiff jerks so easily back into her life later on is never adequately explained, unfortunately – and this represents one of the weaker aspects of the film.] Everybody outside of the horse’s training staff starts to think she’s crazy – and in reality, of course, she is crazy. Most people would not wager their family’s future on a horse winning The Triple Crown. But as we all know, miracles do sometimes happen …

This is the point in the film where we hunker down at the track and really start to see the horses race – because these beautiful and fiery creatures really are miracles. And here the film truly comes to life . The two most significant races shown in the film – The Kentucky Derby, and The Belmont Stakes – play out with almost unbearable suspense, due to Secretariat’s cheeky unwillingness to start a race strong. So at the outset of the Kentucky Derby, Secretariat starts slow again – and Penny’s life dangles before her eyes and ours, and the trainer despairs and threatens to walk out – until … this glorious, powerful, and weirdly arrogant animal called Secretariat takes over and leaves the rest of the field in the dust, smashing Churchill Downs’ track record.

And of course, that’s only the first of Secretariat’s three great races that we see. I won’t spoil the other two for your, but The Belmont is really a whopper …

If I have a quibble with Secretariat, it would be about the racing sequences, however – which are suspenseful and well-paced, but which somehow lack the speed and the grandeur these events have in person. Something this film was crying out for was a large format like IMAX – in the old days, Cinerama would’ve been perfect – because there is something truly awe-inspiring about watching these fantastic animals, with their furious eyes and driving muscles, race wildly around the racetrack. Instead, what Randall Wallace does periodically is to intercut footage shot on consumer-level, high-def camcorders from the jockey’s perspective – and while this brings a certain frenetic intensity to the races, it somehow pulls the movie away from the mythic grandeur it deserves. I mean, this is Secretariat we’re supposed to be watching here – not your kid’s pet pony on YouTube. [By the way, in his retirement Secretariat would sire some 600 foals. No wonder he always looks like he’s smiling.]

That aside, the drama between Chenery and her family gradually subsides in the third act of the film – there are no really dramatic resolutions – in the wake of the awesome spectacle that Secretariat and his victories represented. What we’re left with is the notion that Penny Chenery’s stubborn faith in her horse was validated, far beyond what she or anyone else might have imagined. Basically, she was wildly impractical – crazy – but her persistence paid off. How perfectly American. Only four years before Secretariat’s triumphs, that same kind of craziness and dogged persistence had put American astronauts on the Moon.

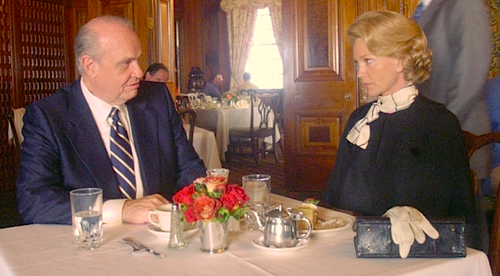

Diane Lane is sensitive, intelligent and strong as Penny Chenery. This is clearly her film, and she’ll likely get an Oscar nomination – although I admit that the film buff in me wonders what Bette Davis would’ve done with this same role. Wow. In any case, it was also great to see Fred Thompson appear briefly as owner ‘Bull’ Hancock. There should be a law requiring all films even tangentially dealing with the American South to feature Fred Thompson, and he should always have a name like ‘Bull’ or ‘Colonel’ or ‘Dutch’ or something like that. It’s good stuff.

I’m a little down on the film’s music, but veteran Aussie cinematographer Dean Semler (The Road Warrior) did a nice job on the film given Wallace’s visual strategy for it – and kudos to the production design team for recreating the early 1970s without lapsing into too much cliché. The costuming also is spot on, and Diane Lane’s suits and hair are almost stars of the film in their own right.

Beyond all that, I’d like to thank Wallace and Mike Rich for having the courage, and gentle good humor, to depict 60’s left-wing/hippie activism for what it so often (if not always) was – a rebellious regression on the part of young kids looking for their parents’ attention.

I doubt very much that Secretariat will become any sort of ‘hot-button’-type film, drawing controversy. The film is much too sentimental and warm-hearted for that, and Disney should expect the film to have a long lifespan as one of the better, ‘inspirational’ sports films. I also tend to think that the ‘Christian subtext’ of the film has been a bit overplayed in the media; beyond a few quotations of scripture, and a few hymns on the soundtrack, there isn’t really very much religious content in the film, at all – and no prosthelytizing of any kind.

Really what the film is about is one plucky, indomitable woman who took a big gamble – and about her stud of a horse, who ironically liked to gamble the same way. Everything paid off big for them both.

Posted on October 8th, 2010 at 8:11pm.