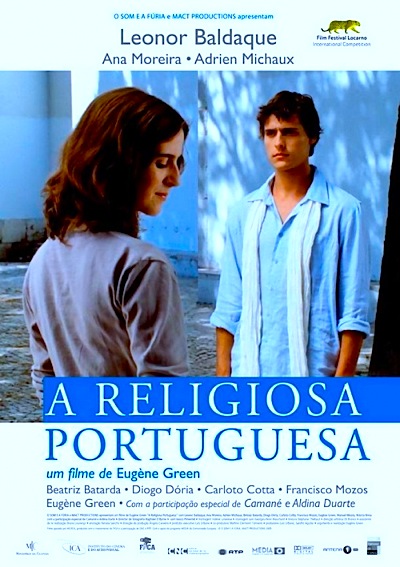

By Joe Bendel. For his latest film, Eugène Green did not set out to adapt The Letters of a Portuguese Nun, the scandalous epistolary romance now attributed to the Comte de Guilleragues, but he plays a director shooting such a project. Yet, even that film-within-a-film is highly unorthodox in Green’s oddly spiritual The Portuguese Nun (trailer here), which opens this Friday at the Anthology Film Archives in New York.

Julie de Hauranne is a Portuguese-French actress fluent in her mother’s language, but making her first trip to Lisbon for Denis Verde’s avant-garde re-working of The Portuguese Nun. There will be no dialogue and few scenes of her together with her co-star. Instead, they are filming the visuals that will accompany their pre-recorded voice-overs. Those rather easy set-calls allow her plenty of time to explore the city. In doing so, she makes a fleeting, but perhaps deep connection to D. Henrique Cunha, a would-be aristocrat disgraced by his family’s connections to the Salazar and Caetano regimes. She also meets Vasco, a veritable street urchin and becomes fascinated with a real Portuguese nun, Sister Joana, who prays nightly at the candlelit Nossa Senhora do Monte Chapel, a place where the spirit could move even an avowed atheist.

If nothing else, Nun will convince viewers Lisbon is a spectacularly beautiful city. The word “picturesque” just does not cut it—not even by half. Its architectural splendor is perfectly matched by a soundtrack of exquisitely sensitive fados. These things are particularly noticeable since Green seems determined to keep the audience at arm’s length from the on-screen drama.

Rarely do Nun’s verbal cadences ever approach anything realistically conversational. Instead, there is a distinctly recitative quality to the dialogue, which Green emphasizes all the more by regularly directing his cast to deliver their lines straight into the camera in self-conscious close-ups. Though de Hauranne is frequently in motion roaming through the city, the film often feels static, like a series of frozen tableaux. Despite the sparkling sheen of Raphaël O’Byrne’s cinematography, Nun has the rigid formality of medieval paintings. Appropriately, it also takes questions of religious faith just as seriously.

Rarely do Nun’s verbal cadences ever approach anything realistically conversational. Instead, there is a distinctly recitative quality to the dialogue, which Green emphasizes all the more by regularly directing his cast to deliver their lines straight into the camera in self-conscious close-ups. Though de Hauranne is frequently in motion roaming through the city, the film often feels static, like a series of frozen tableaux. Despite the sparkling sheen of Raphaël O’Byrne’s cinematography, Nun has the rigid formality of medieval paintings. Appropriately, it also takes questions of religious faith just as seriously.

Though one suspects the “North American born,” French-naturalized Green leans somewhat to the left, there are absolutely no cheap shots taken at Catholicism in Nun. Instead, meeting Sister Joana is a transformational experience for de Hauranne. In an exchange one could never find in a Hollywood film, the saintly Nun explicitly connects faith and love with words that are powerful, because they are spoken with humility. Likewise, instead of being a snarky Bill Maher, the worldly actress’s questions elicit heartfelt responses, because they are meant in good faith, so to speak.

Frankly, Nun is a strange film to get a handle on. At times, Leonor Baldaque is so deliberately inexpressive as De Hauranne, she could be mistaken for a bad CGI effect. Though essentially playing himself, Green is nearly just as stiff when appearing as Verde. Conversely, Diogo Dória’s turn as the haunted Cunha is deeply compelling and fundamentally humane, while Ana Moreira radiates piety as Sister Joana.

In terms of method and tone, Nun almost approaches experimental filmmaking, yet it has a romantic soul and a respect for the transcendent faith of Sister Joana that borders on genuine reverence. It also shows unexpected flashes of sardonic wit. Clearly, Nun is intended for an exclusive, self-selecting audience, yet it has moments of arresting beauty well beyond the sights and sounds of Lisbon. It would surely baffle multiplex audiences several times over, but the elusive Nun is highly recommended to the stylistically adventurous. It opens this Friday (10/22) in New York at the Anthology Film Archives.

Posted on October 21st, 2010 at 9:55am.