By Jason Apuzzo. “Well, the time has come to ask, is ‘dehumanization’ such a bad thing? Because good or bad, that’s what’s so. The whole world is becoming humanoid, creatures that look human but aren’t. The whole world, not just us. We’re just the most advanced country, so we’re getting there first. The whole world’s people are becoming mass-produced, programmed, numbered, insensate things useful only to produce and consume other mass-produced things, all of them unnecessary and useless as we are …” – Howard Beale, from Paddy Chayefsky’s Network (1976).

“What strikes me is the fact that in our society, art has become something which is only related to objects, and not to individuals, or to life.” – Michel Foucault.

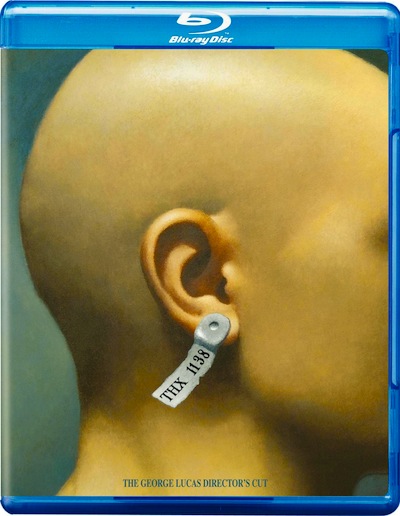

I thought I would take a little time out today from the usual run of events here at Libertas to review a favorite film of mine that for various reasons I’ve been thinking a lot about lately: George Lucas’ THX: 1138 from 1971. There is an excellent, new Blu-ray edition of the film available out there for you collectors right now, and I recommend it highly.

THX: 1138 is probably best known as the film that started – and almost ended – George Lucas’ directing career. The film was based on a student short Lucas did at the USC Cinema School called “Electronic Labyrinth THX 1138:4EB” (the “EB” standing for “Earth Born”; THX-1138 was actually Lucas’ phone number at the time). That student short, incidentally, happens to be included in the Blu-ray edition, and is definitely worth watching. Around USC Cinema circles the short is something of a legend – in large part because it does everything a short is supposed to do: tell a powerful story quickly, visually, by ‘cutting to the chase’ as fast as possible. In fact, the original “Electronic Labyrinth THX 1138:4EB” is nothing but a chase, involving a lone future-worker’s escape from a totalitarian society.

The story of how “Electronic Labyrinth THX 1138:4EB” got translated into a feature is a long and complex one; suffice it to say the crucial players were Francis Coppola and his newly formed American Zoetrope Studios, plus the cabal of USC Cinema friends Lucas dragged up to the Bay Area with him (most notably Walter Murch), plus a few key executives at Warner Brothers like John Calley – who would later stab Lucas and Coppola in the back once the film was completed. And actually the fascinating, behind-the-scenes story of THX: 1138‘s creation is essentially the story of American Zoetrope itself – the fledgling dream of Francis Coppola to found a Bay Area filmmaking colony of independent artists, set up in opposition to the factory-mentality of Hollywood. Appropriately, the Blu-ray features a great documentary on the founding of American Zoetrope, and the role THX: 1138 played in that company’s rise and fall … and rise again.

So what, then, is THX: 1138 about? The film focuses on a worker in a futuristic, dystopian, police-state underworld who begins to have a crisis of conscience about his meaningless life and the oppressive, stultifying world he lives in. He rebels – awkwardly at first (he stops taking his tranquilizers, makes illicit love to his roommate, etc.) – and then finally decides to escape.

And that’s really it – the entire film in a nutshell.

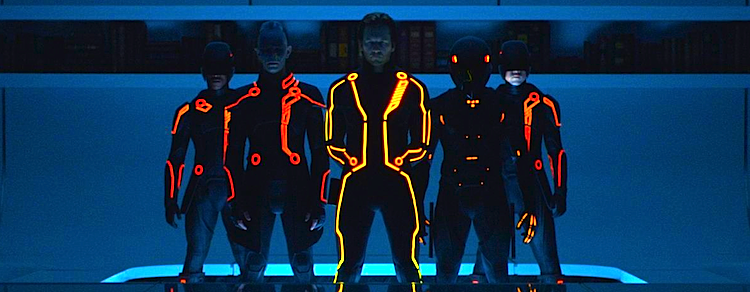

What makes THX: 1138 worthwhile and interesting as a film is the striking world Lucas creates out of what was a very modest budget at the time – exactly $777,777, to be precise (executive producer Coppola was superstitious about numbers). The key to the film’s arresting, futuristic ‘look’ – a look that now seems prescient – is what might be described as a Japanese minimalism, combined with a similarly Japanese emphasis on bold, static compositions and a simple color palette.

Lucas initially wanted to film THX: 1138 in Japan, for two reasons. First, Japan seemed at the time to be the most futuristic of countries with respect to its integration of technology into the normal flow of living. (It still seems to be that today.) Secondly, Lucas and Walter Murch (who edited and co-wrote the film) were into Japanese movies at the time – particularly those of Kurosawa and Ozu. They were fascinated by the ‘alien,’ non-Western quality of Japanese rituals – and the degree to which Japanese filmmakers made no effort to explain these rituals for non-Japanese audiences. This ‘alien’ quality was exactly what Lucas and Murch were looking for in order to depict a futuristic society in which individual identity was put in jeopardy.

One is tempted to think here of Marshall McLuhan, who around the time of THX was proposing that the whole world was becoming “orientalized,” and that in the future none of us would be able to retain his or her cultural identity – “not even the Orientals.”

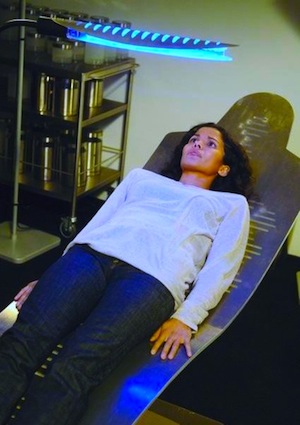

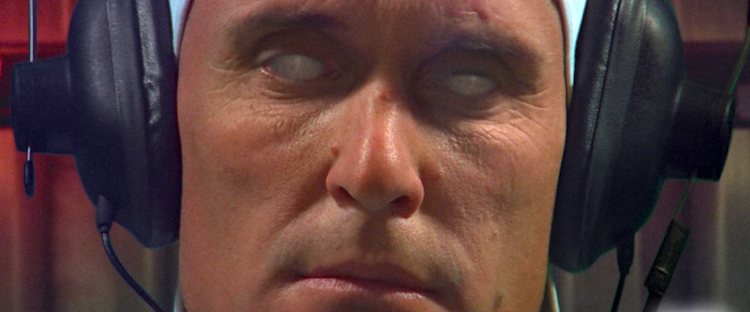

We begin the film with THX (played with subdued intensity by Robert Duvall) at work on an assembly line, helping to put together what basically look like droids. He’s having a tough time of it, though, not able to maintain his concentration or focus. Is he having psychological problems? We don’t yet know. In THX’s world, all emotions are suppressed through the compulsory use of drugs – drugs that resemble “soma” from Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World.

An early crisis comes in the film when THX’s female roommate ‘LUH 3417’ (Maggie McOmie) stops taking her drugs, and secretly substitutes a placebo for THX’s normal tranquilizer. As THX’s sedative wears off, he finds himself experiencing emotions, doubts, even sexual desire. Chief among these emotions is anxiety, and his work at this point definitely begins to be affected.

Nothing he tries helps. THX goes home, for example, to watch TV – actually holograms. TV in the future, however, has basically been reduced to three different sorts of programming: 1) mindless, sadistic violence; 2) porn; 3) glib, meaningless ‘talk shows.’ Sound familiar?

Nothing he tries helps. THX goes home, for example, to watch TV – actually holograms. TV in the future, however, has basically been reduced to three different sorts of programming: 1) mindless, sadistic violence; 2) porn; 3) glib, meaningless ‘talk shows.’ Sound familiar?

Everything in THX’s world, incidentally, is impersonal and automated. For example, looking for solace, poor THX visits a kind of high-tech confessional booth which features a generic religious icon (known as “Ohm”) who mutters impersonal, pre-recorded platitudes. “My time is your time … blessings of the State, blessings of the Masses … work hard, and be happy.” THX vomits in one of the confessionals, so disgusted is he by what he hears. He goes home to masturbate (off-screen) – although he’s only able to do so with help of an automated machine. In Lucas’ future, all forms of private experience have been automated, regulated, rendered ‘technological.’

THX is eventually incarcerated for his ‘bad behavior,’ and dragged off to a white limbo prison – where he encounters a group of maladjusted freaks similar to the crowd Jack Nicholson encounters in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. My favorite in this group is Donald Pleasence playing ‘SEN 5241’ – a cliché-spouting, bureaucratic functionary. Pleasence’s dialogue in this portion of the film is really delicious, filled with ridiculous platitudes and non-sequiturs. It’s actually some of the funniest stuff Lucas has ever written.

The ‘prison’ in this portion of the film has a Waiting for Godot/existentialist quality to it, in so far as there are no walls of any kind. In fact, THX’s big decision to ‘escape’ the prison consists merely in Duvall’s deciding to walk away into the unseen distance. That’s it. Lucas’ point here could not be clearer: most of the walls we experience in life are illusory, and self-created. Sometimes all we need do is walk away from what’s holding us back.

And, interestingly, most of the prisoners in THX’s white limbo prison are afraid to escape – even though nothing is physically holding them back. Eventually THX and SEN make their way out into limbo on their own, where they encounter ‘SRT’ (Don Pedro Colley), who is actually a hologram who’s managed to escape the underground world’s computer network. SRT reminds one here of the Tin Man from Wizard of Oz, or of C-3PO from Lucas’ later Star Wars. Even robots apparently need a little freedom, too.

THX eventually discovers LUH’s tragic fate, which has a little bit of a ‘Lot’s wife’ feel to it, and then an extended escape sequence begins through the city’s vast underground road network. THX is chased here by android police on motorcycles, and to this day I’ve never understood how Lucas got guys to drive that fast on motorcycles with faceplates on. Weird.

The robot police pursue THX up toward the surface, but – and this is one of the film’s more arch, ironic touches – the budget expenditure allotted to capture THX becomes too great, so the computers tell the robot cops to stand down! Beautiful. Those future dystopias are always running out of money, aren’t they?

We finish the film with an incredible shot that is best appreciated on Blu-ray. After spending the entire film underground, in artificial lighting, THX emerges onto the surface of the Earth in front of an enormous, orange, blazing sun – photographed with what must have been a 1000mm lens. It’s a striking scene that is repeated in 1977’s Star Wars, when Luke Skywalker gazes out on the twin setting suns of Tatooine, contemplating a future of adventure and freedom he doesn’t believe he’ll ever have. In THX’s case, he certainly does achieve his freedom – although the exact nature of that freedom, and of his future, remains unclear.

We finish the film with an incredible shot that is best appreciated on Blu-ray. After spending the entire film underground, in artificial lighting, THX emerges onto the surface of the Earth in front of an enormous, orange, blazing sun – photographed with what must have been a 1000mm lens. It’s a striking scene that is repeated in 1977’s Star Wars, when Luke Skywalker gazes out on the twin setting suns of Tatooine, contemplating a future of adventure and freedom he doesn’t believe he’ll ever have. In THX’s case, he certainly does achieve his freedom – although the exact nature of that freedom, and of his future, remains unclear.

Thus ends THX: 1138. And now comes the $64 million question: on the whole, is the world of THX relevant to the world of today?

I think the answer must be: yes.

Are we currently living in a world in which the government is intruding into too many aspects of our daily lives – and using advanced technologies to pry into our privacy … even beneath our clothing? Of course we are. And why do we allow this? Because we’ve been brainwashed into believing that it’s necessary, and that a benevolent state apparatus has our best interests in mind.

I’m reminded here, among so many other things, of what is currently going on at our nation’s airports. All of us are now being scanned, X-rayed and disrobed at our airports if we commit the crime of wanting to fly. Book a flight to New York, for example, and you’re likely to find yourself stripped in public – or having your naked form recorded onto a government hard drive. (“Don’t worry – we’ll make sure it gets erased!”) And so a commercial flight can now turn into an exercise in exhibitionism, an opportunity to get scoped-out and humiliated by a government official – all for the crime of traveling.

But that’s not all. New devices are now being marketed that conduct psychometric exams of airline passengers, who are required to answer a battery of questions (to a computer) to determine whether they fit a pre-defined psychological ‘profile’ of someone wanting to blow-up an airplane. Our own Homeland Defense officials are apparently very interested in this technology. And why wouldn’t they be? (After all, perhaps they could even determine if someone might attend a Tea Party rally.)

As citizens and as customers, why do we put up with this? We do so because we’ve been brainwashed, made docile (and literally, in many cases, sedated with drugs), and ultimately because we want to put up with it. Because we’ve been sold the politically correct bill-of-goods that all ‘humanoids’ – whether they be Gramma Betsy from Kenosha, or 18-year old Ahmed from Lahore – are just as likely to blow up a plane as anyone else. Why? Because bureaucratically we’re all the same – just numbers in a system. And if you happen stand up and protest this madness, if you complain about ‘the system’ and its obvious inadequacies and dangers – you can expect to be accused of being a bad person. You’re not with the program! You’re ‘off your meds,’ ‘hateful,’ ‘paranoid’ and a danger to public safety.

This is the world we live in, and this is the world of THX. Indeed it’s altogether amazing – and unnerving – how almost everything about Lucas’ film seems appropriate today.

A few final words about the Blu-ray itself: the image on this film is fantastic; also, Walter Murch did some of the most striking sound design work of his career on this film, and there are superb documentaries (”Master Sessions”) on the Blu-ray that cover that subject for the cinephiles out there.

One quibble I have with the film is its portrayal of sex in the future: namely, there is none. Lucas decided to go the Orwell/1984 route and predict a ’sexless’ future in which children are created primarily in test tubes. Needless to say, I don’t think a sexless future is on our horizon – at least here in the West. Sex is omnipresent and omnipotent today, so Lucas probably would’ve been shrewder to go with Aldous Huxley and Brave New World, or with Yevgeny Zamyatin and We, and predict an orgiastic/promiscuous future in which monogamy is forbidden and children are collectively raised ‘by a village.’ (Lucas otherwise seems to have borrowed the shaved heads and number-names from Zamyatin, or perhaps from Ayn Rand’s Anthem?) This orgiastic/group-sex/collective consciousness future seems much closer to where we’re headed, and the subject of sexual relations is the only area where THX: 1138 seems off-kilter.

THX: 1138 is a great experimental film, however, with a lively and sardonic sense of humor about our world. Underneath that humor, of course, is an authentic social critique of our society – as we march happily toward a future of conformism, sedation, docility and political correctness.

Work hard, and be happy.

Posted on January 17th, 2011 at 1:28pm.