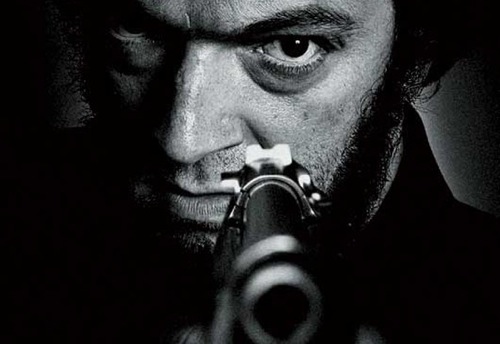

By Joe Bendel. Gangster and self-styled revolutionary Jacques Mesrine never lacked for nerve, but he might have started to believe his own hype. That never turns out well. At least we have good reason to believe he will not go quietly at the conclusion of Mesrine: Public Enemy #1, the second part of Jean-François Richet’s two-film bio-epic, which opens today in select theaters nationwide.

After his notorious detour through Quebec, Mesrine is back in France, plying his chosen trade. A celebrity criminal who assiduously cultivates the media, his capture becomes the top priority of Police Commissaire Broussard. Actually, catching the flamboyant Mesrine seems relatively easy – keeping him behind bars was the tricky part. When he teams up with François Besse, an unassuming but equally slippery fellow inmate, all bets are off.

After his notorious detour through Quebec, Mesrine is back in France, plying his chosen trade. A celebrity criminal who assiduously cultivates the media, his capture becomes the top priority of Police Commissaire Broussard. Actually, catching the flamboyant Mesrine seems relatively easy – keeping him behind bars was the tricky part. When he teams up with François Besse, an unassuming but equally slippery fellow inmate, all bets are off.

Largely eschewing the personal drama of Killer Instinct, Public features two shoot ‘em up escape sequences, a number of mostly disastrous capers, some cold-blooded killing, and the brilliantly edited conclusion. Essentially, Public delivers the pay-off on Instinct’s emotional investment. Yet all the really juicy supporting turns come in the second, action-driven film. As Besse, the perfectly cast Mathieu Amalric (The Diving Bell and the Butterfly) is an intense counterpoint to blustery Mesrine. Likewise, Dardenne Brothers regular Olivier Gourmet brings some heft to Broussard, making him a worthy antagonist for Mesrine. Instinct standout Michel Duchaussoy also makes a brief but touching return appearance as the gangster’s meekly loving father.

Of course, it’s problematic using terms like “hero” or even “anti-hero” with regard to the Mesrine films. While most of his outright misogynistic episodes come in the first installment, he is consistently presented as a problematic figure, albeit one not without charm. Arguably, though, it is his effort to preserve his good press that contributes to his undoing. Vanity—it’s a killer.

While Instinct had the occasional slow patch, Enemy speeds along like an escaped fugitive. It is all held together by Vincent Cassel’s dynamic lead performance and the film’s cool, retro-70’s look. Of course, the Mesrine films are best seen as a whole, but of the duology Enemy is definitely the superior film. It opens today in select theaters nationwide.

Posted on September 3rd, 2010 at 10:21am.