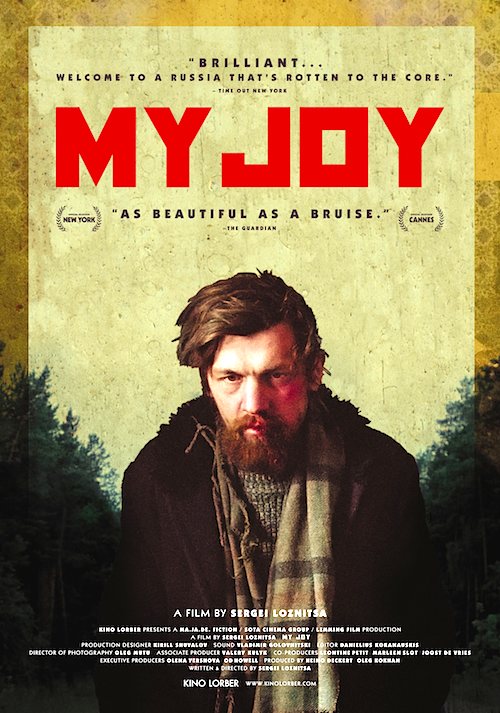

By Joe Bendel. Like any place, Russia has its share of urban legends, but Russia’s seem to carry the oppressive weight of the country’s tragic history. At least, such seems to be the case with the stories that inspired documentarian Sergei Loznitsa’s narrative feature debut, My Joy (trailer here), which opened yesterday in New York.

By Joe Bendel. Like any place, Russia has its share of urban legends, but Russia’s seem to carry the oppressive weight of the country’s tragic history. At least, such seems to be the case with the stories that inspired documentarian Sergei Loznitsa’s narrative feature debut, My Joy (trailer here), which opened yesterday in New York.

Having spent considerable time on the road, truck driver Georgy is no babe in the woods. He is hardly shocked by the venal cops who hassle him or the teenaged (if that) prostitute hustling business when a major accident closes the highway. Still, he tries to help her, but like contemporary Russia, she will have none of it. However, his trip goes seriously awry when he tries to take a detour around the backed-up traffic.

Though not overtly supernatural, the fateful back road takes the driver into a very malevolent place, somewhat in the spirit of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Like a horror film written by Beckett, Georgy is sucked into an absurdist village, where predatory behavior is the norm. Time becomes indeterminate in this twilight world, with the tragic past echoing strongly in the corrupt present day.

This is particularly true of an old hitchhiker’s story, easily the film’s strongest mini-arc. According to the mysterious stranger, he had been a heroic Lieutenant during WWII, but when a crooked local Commander robbed and humiliated him, his response permanently relegated the man to the nameless margins of Russian society. One of many discursive interludes, the Lieutenant’s flashback is rather bold because it directly challenges the great patriotic mythos built around the Soviet war years, as do the mutterings of a quite possibly mad veteran, apparently boasting of a Katyn Forest style massacre, heard later in the film.

Loznitsa presents a vision of a country sick in psyche, where those who have served it best are victimized the worst. He does not exactly tell this story in a straight line, bouncing off characters and subplots like a pinball. Frankly, Joy can be a little tricky to follow, but the heavy parts are hard to miss. Continue reading Absurdist Visions of Russia: LFM Reviews My Joy