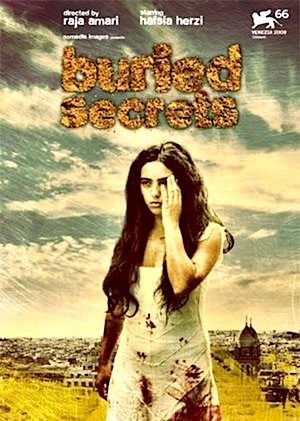

By Joe Bendel. Consider this as Upstairs, Downstairs in its darkest manifestation. In a secluded Tunisian mansion, Aïcha is squatting in the basement servants’ quarters with her domineering mother and world-weary older sister. It is not much of a life, but at least it is quiet, until the original owner’s grandson arrives with his lover. The inadvertent intrusion of differing values and lifestyles profoundly disrupts their dysfunctional family unit in Raja Amari’s Buried Secrets (trailer here), the gala selection of this year’s African Diaspora International Film Festival.

Largely uneducated but devout, Aïcha’s family barely earns a subsistence living through embroidery work. At least their cloistered existence allows Radia and her mother to keep Aïcha under control. They clearly consider her somewhat off, but it is initially unclear whether she really is a tad slow or has simply never had any outside social interaction. When Ali and his girlfriend Selma arrive, she is magnetically attracted to their fashionable clothes and open affection. Needless to say, her mother considers the “interlopers” indecent, but since they have no right to be there, the three women can only surreptitiously cower in the cellar. Inevitably, Selma discovers their presence in the crumbling manse, prompting the older women to take a rash course of action.

Ironically, the downstairs goings-on are considerably more scandalous than anything happening upstairs in Buried. Though viewers might guess at some of Aïcha’s family secrets, their revelation takes the women to some pretty shocking places. Amari clearly suggests the mother’s ultra-traditional Islamic upbringing has a stunting effect on Aïcha’s sexual maturity, but this is not a reassuring tale of female empowerment. What starts as a class-conscious social issue film morphs into a dark fairy tale, before finally settling into a psychodrama. Yet, somehow Amari maintains a consistent mood while keeping the audience off-balance.

Ironically, the downstairs goings-on are considerably more scandalous than anything happening upstairs in Buried. Though viewers might guess at some of Aïcha’s family secrets, their revelation takes the women to some pretty shocking places. Amari clearly suggests the mother’s ultra-traditional Islamic upbringing has a stunting effect on Aïcha’s sexual maturity, but this is not a reassuring tale of female empowerment. What starts as a class-conscious social issue film morphs into a dark fairy tale, before finally settling into a psychodrama. Yet, somehow Amari maintains a consistent mood while keeping the audience off-balance.

The grand old home is wonderfully cinematic (sort of like a Tunisian Grey Gardens), anchoring the film in a specific, strange and isolated place. However, it is Hafsia Herzi’s remarkable performance as Aïcha that makes it all come together. Simultaneously vulnerable and unnerving, it is impossible to take your eyes off her. Arguably though, Rim El Benna’s work is even braver, portraying Selma as a sympathetic, emotionally complex modern woman. Her more revealing scenes also likely generated the predictable disapprobation from Tunisia’s intolerant religious quarters.

Intriguing in many respects, Buried creates an eerie vibe of life in a state of twilight-limbo, implying rather than showing the great repercussions of its accidental clash of cultures. Fittingly, it is another challenging cinematic statement handled by Fortissimo Films, the focus of a recent retrospective at MoMA. Definitely recommended, it screened as part of the ADIFF gala with a regular festival screening to follow next week (12/11).

Posted on December 5th, 2011 at 2:44pm.