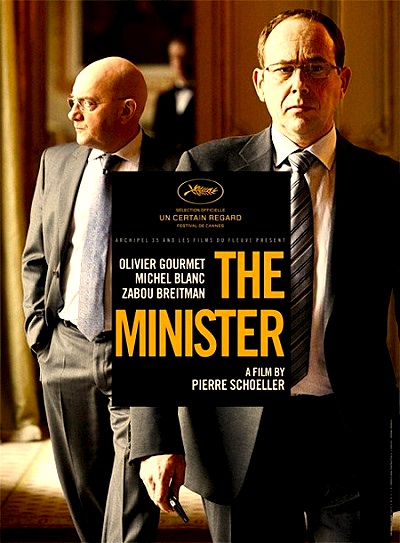

By Joe Bendel. Imagine Jonathan Lynn’s Yes, Minister played deadly seriously, in French. Such is the morality tale director-screenwriter Pierre Schöller has to tell. Bertrand Saint-Jean is a dull technocrat, but he does not lack ambition. He has built up his portfolio through the help of his loyal secretary, a respected veteran of the civil service. However, a series of political crises will shine a harsh light on his flawed character in Schöller’s The Minister (trailer here), which screens during the 2012 New Directors/New Films, jointly presented by the Film Society of Lincoln Center and MoMA.

By Joe Bendel. Imagine Jonathan Lynn’s Yes, Minister played deadly seriously, in French. Such is the morality tale director-screenwriter Pierre Schöller has to tell. Bertrand Saint-Jean is a dull technocrat, but he does not lack ambition. He has built up his portfolio through the help of his loyal secretary, a respected veteran of the civil service. However, a series of political crises will shine a harsh light on his flawed character in Schöller’s The Minister (trailer here), which screens during the 2012 New Directors/New Films, jointly presented by the Film Society of Lincoln Center and MoMA.

The transport minister is woken from a wildly Freudian dream with grim news. A charter bus was involved in a severe traffic accident, killing many school children returning from a class trip. Saint-Jean heads to the crash site to lead the investigation and keep the media at bay. It will be his finest hour in the film, as a politician and a human being.

Subsequently, Saint-Jean’s public standing gets a nice little bump, but it is short-lived. Soon thereafter, he is a pulled into a controversy involving the privatization of train stations. Like his secretary Gilles, he is adamantly opposed, but the finance minister is in favor. In fact, it seems to be required by the EU, but Saint-Jean would prefer to kick the can down the road for his successor to deal with. Yet, it seems he will be forced to make some difficult choices, for the sake of his political career.

It is hard to think of a more cynical depiction of “the art of compromise” than Schöller’s Minister. As a former idealist, Saint-Jean’s self-contempt is palpable. Viewers watch some rather brazen pandering, including the temporary hiring of a long-term unemployed blue collar working as a ministerial driver, purely for PR purposes. Yet, despite the central role played by the privatization plan, Schöller’s screenplay sidesteps the issues of its normative and qualitative economic merits quite nimbly. Instead, it is treated simply as the MacGuffin to test Saint-Jean’s principles and loyalties. However, the Minister’s long, drunkenly patronizing visit to his new driver’s home rings distractingly false.

For the most part though, Dardenne Brothers regular Oliver Gourmet raises blandness to levels of epic tragedy as Saint-Jean. Yet there is something downright Clintonesque about his insecure need for approval. It is a shrewdly restrained but neurotic performance. Conversely, Michel Blanc makes mousiness dignified as the old school bureaucrat, ever loyal to his boss, as the embodiment of the system he has always served.

For those who really want to follow the specific issue at hand, the film’s treatment does not always make sense. Regardless, Schöller wields it effectively to cleave divisions in Saint-Jean’s staff and party. What emerges is a sort of modern Faust, as Saint-Jean makes the same awful bargain over and over again. Rare among political films, The Minister forthrightly depicts the psychological baggage of politicians in a way that can be appreciated by audiences across a wide ideological spectrum. Recommended for intelligent, slight jaded patrons, it screens this Friday (3/23) at MoMA and Sunday (3/25) at the Walter Reade Theater.

Posted on March 19th, 2012 at 2:28pm.