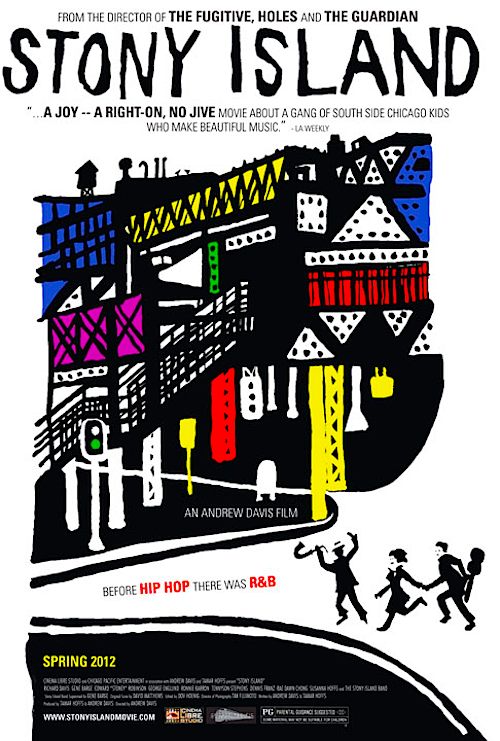

By Joe Bendel. Some things never change. In the late 1970’s, Chicago was home to musicians who played the blues and crooked politicians who gave them, just as it is now. For his feature directorial debut, future Fugitive helmer Andrew Davis captured the vibe of his hometown in the hip musical drama Stony Island (a.k.a. My Main Man from Stony Island). Despite the talent involved in the production, it has been nearly unseen for decades, known mostly to diehard record collectors familiar with the smoking hot soundtrack LP. Happily, this will soon change. Stony Island screens this Wednesday and Thursday at Chicago’s Gene Siskel Film Center, in advance of it April 24th DVD release from Cinema Libre.

Guileless guitarist Richie Bloom has come to Chicago with a dream. He wants to start a band, so he does with the help of his vocalist Stony Island neighbor Edward “Stoney” Robinson and Percy Price, a beloved tenor sax veteran of the Chicago music scene. Slowly, they piece together a grooving big-funk band, but just as it all starts to click, Price, their spiritual leader, tragically dies. With their first big gig on the horizon, the Stony Island Band must pull together to find a way to give the destitute Price a proper send-off.

Comprised largely of tunes arranged and composed by David Matthews (the CTI Records house arranger), the Stony Island soundtrack should have been more sought after by vinyl hounds. Though ostensibly R&B, the Stony Island Band often plays more in a greasy soul jazz bag, which is very cool. A lot of great musicians’ musicians appear in the film, such as Chess Records mainstay Gene Barge, making a strong impression as Price. Those heard but not seen include studio warriors like alto saxophonist David Sanborn (during his groovy CTI, pre-smooth days), guitarist Hiram Bullock, and bassist Mark Egan.

Comprised largely of tunes arranged and composed by David Matthews (the CTI Records house arranger), the Stony Island soundtrack should have been more sought after by vinyl hounds. Though ostensibly R&B, the Stony Island Band often plays more in a greasy soul jazz bag, which is very cool. A lot of great musicians’ musicians appear in the film, such as Chess Records mainstay Gene Barge, making a strong impression as Price. Those heard but not seen include studio warriors like alto saxophonist David Sanborn (during his groovy CTI, pre-smooth days), guitarist Hiram Bullock, and bassist Mark Egan.

Some of Island’s musician-actors are a bit awkward on-screen, but they always mean well. In contrast Barge gives a fantastically soulful and assured performance as Price, the Obi-Wan Kenobi of funk. Likewise, Ronnie Barron, a onetime sideman to just about everyone from New Orleans, brings the film a fresh jolt of energy as keyboard player Ronnie Roosevelt. His NOLA arrangement of “Just a Closer Walk with Thee” is also one of the film’s highlights.

Viewers should keep an eye out for jazz vocalist Oscar Brown, Jr. in a nonmusical role as the corrupt Alderman Waller. Ironically, a young Rae Dong Chong has a mostly musical rather than dramatic part, appearing as Janetta, a back-up vocalist. Likewise, Susanna Hoffs, the future Bangle and daughter of co-writer-co-producer Tamar Hoffs, never sings a note as Bloom’s girlfriend Lucie.

Even more than his crime dramas like Code of Silence, Davis vividly conveys to viewers of Island a sense of Chicago, soaking up its distinctive sights and sounds. He even uses Daley Sr’s real life funeral as a surreal backdrop. Considering the future big name stars appearing here early in their careers (Dennis Franz as a sleazy hustler? You bet) and the highly regarded (if not exactly world famous) musical talent heard throughout, it seems downright bizarre the film was not reissued far earlier. Cheers to Cinema Libre for getting it.

Granted, the let’s-get-a-band-together story is a bit predictable, but its earnest enthusiasm is endearing. Sentimental in the right way, Island feels like the last gasp of big city innocence. Featuring a swinging, funk-drenched soundtrack and a wonderfully humane supporting turn from Barge, Island is a criminally neglected movie musical gem. Highly recommended for blues-funk-R&B-soul jazz fans, Davis will personally present both screenings at the Siskel Center this Wednesday (4/4) and Thursday (4/5), with the mother and daughter Hoffses set to attend both nights and the great Barge also scheduled to appear at the first screening. For those outside Chicago, it releases nationwide on DVD and screens at Los Angeles’ American Cinematheque on April 24th.

Posted on April 3rd, 2012 at 2:25pm.