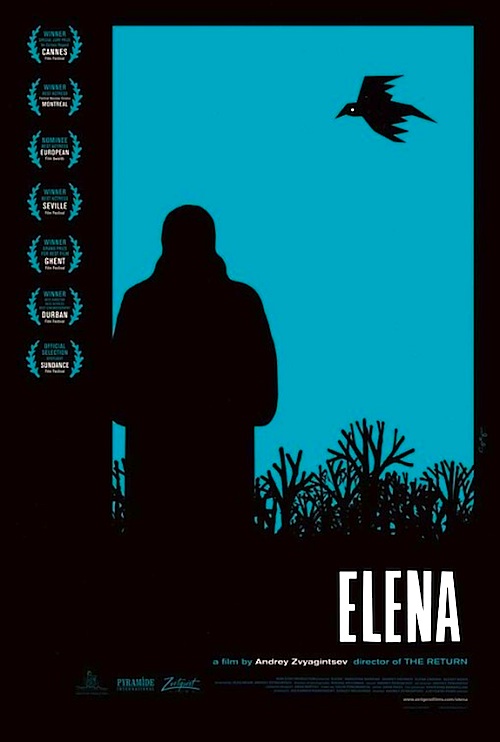

By Joe Bendel. Elena could have been an old world Russian babushka. She even still wears the traditional head scarves. Yet, she has married into the world of oligarchic privilege. It is a pleasant if loveless marriage, but fundamental disagreements with her wealthy husband will take a dark turn in Andrey Zvyagintsev’s Elena, which begins a special two week engagement at New York’s Film Forum this Wednesday.

The working class Elena met the sophisticated Vladimir while working as a nurse during his convalescence two years ago. They have little in common except their dismal records as parents. His grown daughter Katerina is an entitled party girl emblematic of New Russia’s excesses. Elena’s slobby, unemployed son Sergey is only fit for queuing in lines and getting drunk. That might have been perfectly fine during the Soviet era, but it does not cut the mustard any more. While Vladimir readily underwrites Katerina’s high-flying lifestyle, he begrudges any support Elena offers her deadbeat family.

If anything, Elena’s thuggish grandson Sasha is even less accomplished than his father. In order to forestall his military service, Sergey will have to bribe Sasha’s way into college, but Vladimir is not having any of it. After collapsing in the gym, issues of inheritance come to the fore, provoking Elena to action for the sake of her proletariat family.

If anything, Elena’s thuggish grandson Sasha is even less accomplished than his father. In order to forestall his military service, Sergey will have to bribe Sasha’s way into college, but Vladimir is not having any of it. After collapsing in the gym, issues of inheritance come to the fore, provoking Elena to action for the sake of her proletariat family.

Such “action” is a relative term in Zvyagintsev’s deliberately paced film. He is much more interested contrasting the dramatic class distinctions of contemporary Russian than engaging in Double Indemnity style suspense. Frankly, viewers need to pay attention throughout Elena, because it is easy to miss the crossing of the Rubicon.

In contrast, it is impossible to not notice the differences between the two Russias. One is a world of glass and steel luxury (perfectly underscored by sparing excerpts from Philip Glass’s 1995 Symphony No. 3), whereas the other is a grubby suburb of Brutalistic socialist era architecture dominated by noxious looking nuclear containment domes. There is also a pronounced psychological difference, as well. Vladimir harshly dismisses Sergey as a lazy drunken slacker, but he is not exactly wrong.

Indeed, a mother’s love may oftentimes be blind (it might have been clever to have opened Elena over the weekend, but it is hard to imagine any son taking mom to see it) and Elena is arguably indulgent to a fault. However, it is her relationship with Vladimir that is most intriguing. Nadezhda Markina palpably conveys a complicated lifetime of struggle as the title protagonist, while developing some ambiguous yet very real chemistry with actor-director Andrey Smirnov’s Vladimir. The precise nature of their union remains hard to pigeonhole, with several scenes supporting disparate interpretations.

Elena certainly shines a spotlight on the inequalities of Putin’s Russian – still a playground for compliant oligarchs. Yet, as a film it is really a showcase for Markina’s remarkable, unadorned performance. Though the tempo is undeniably leisurely, there is a real point to it all, as it heads towards a very specific destination. Recommended for viewers with adult attention spans, Elena opens this Wednesday (5/16) at Film Forum.

LFM GRADE: B

Posted on May 15th, 2012 at 3:57pm.