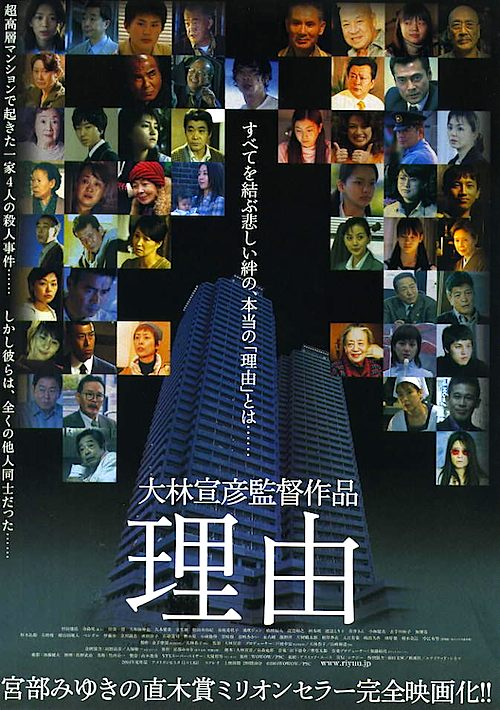

By Joe Bendel. It was a multiple murder New Yorkers can well understand. It directly involved the struggle to buy and keep possession of an under-valued luxury condo. However, darker, more passionate motives also contributed to the deaths of four unrelated people in unit 2025. Eventually, an intrepid writer will mostly reveal the truth in Nobuhiko Obayashi richly complex mystery Reason (a.k.a. The Motive), which screens during the Japan Society’s Obayashi retrospective.

By Joe Bendel. It was a multiple murder New Yorkers can well understand. It directly involved the struggle to buy and keep possession of an under-valued luxury condo. However, darker, more passionate motives also contributed to the deaths of four unrelated people in unit 2025. Eventually, an intrepid writer will mostly reveal the truth in Nobuhiko Obayashi richly complex mystery Reason (a.k.a. The Motive), which screens during the Japan Society’s Obayashi retrospective.

As the super explains during his many interviews, the unit in question always had high turnover. On the night in question, they assumed the rather unsociable Koito family were the victims, but they had secretly moved out. Suspicion therefore focused on Naozumi Ishida, who had purchased the condo through a repossession auction. We know from the in medias res opening, the weary Ishida will eventually turn himself into the authorities. At his request, Nobuko Katakura, the daughter of the innkeepers reluctantly hosting the fugitive will bring the disbelieving local copper.

Throughout her investigation, the journalist will piece together a deliciously complicated story, enveloping the Koitos, the Ishidas, several sets of neighbors, and even the Katakuras. Of course, there are four dead bodies to explain: one who fell from the balcony of number 2025 and three others found brutally murdered within. Yet, aside from the crime scene, there is no obvious link between the apparent strangers. This is all quite disturbing to the residents of the two-tower complex, but despite his own family’s growing notoriety, young Shinji Koito is inexplicably drawn back to his former home.

Reason is a wonderful rich and methodical film that takes its time to build a remarkably full picture of residents and the people in their orbits. Although rarely seen, Yuri Nakae selflessly holds the film together as the journalist, much like William Alland in Citizen Kane, except she actually gets the answers she is looking for. Reason probably has thirty or forty meaty roles, each of which is memorably executed. Terashima Saki is terrific as the empathic Nobuko Katakura and Ayumi Ito is desperately haunting as Ayako Takarai, a mysterious teenaged mother who eventually crosses paths with Ishida and company. However, Ittoku Kishibe really provides the film its reflective soul as the building super, who is constantly re-interviewed to give us more context.

Obayashi and Shirȏ Ishimori’s adaptation of Miyuki Miyabe’s novel gives us enough answers to satisfy according to mystery genre standards, but leaves enough messy loose ends to remind us truth is problematic in an era of uncertainty. The story also takes a cautiously metaphysical twist in its closing sequences, wholly in keeping with Obayashi’s oeuvre. In many ways Reason is a dark film, but it is just a joy to watch him construct layer on top of layer. It is also a good value for you ticket dollar, considers it runs a full one hundred and sixty minutes. Cineastes and mystery fans of all stripes who will be in New York this weekend should make every effort necessary to see Reason when it screens this Sunday (12/6) as part of the Obayashi retrospective at the Japan Society.

LFM GRADE: A+

Posted on December 4th, 2015 at 10:52am.