[Editor’s Note: This post appears today at The Huffington Post and at AOL-Moviefone.]

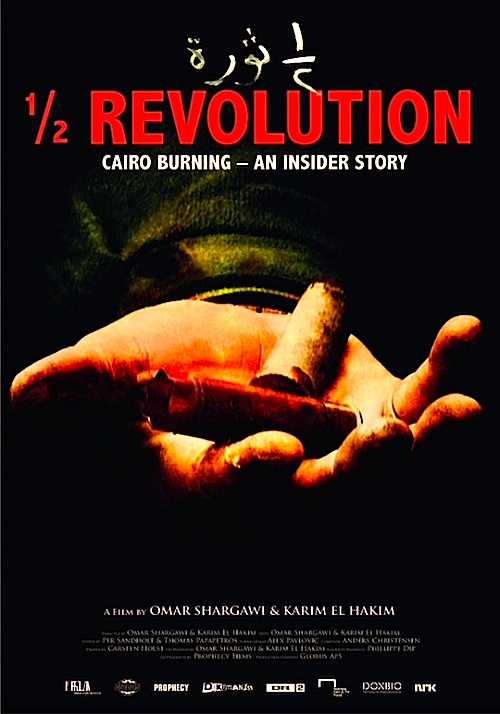

By Govindini Murty. As the Egyptian military government prepares to put nineteen American employees of pro-democracy NGOs on trial, and thousands of Egyptians continue to demonstrate over the stalling of democratic reforms, the new documentary 1/2 Revolution offers a striking look back at the Egyptian revolution of one year ago.

Premiering recently at the 2012 Sundance Film Festival, 1/2 Revolution depicts the revolution through the eyes of a group of Egyptian activists directly involved in it. Using cell phone cameras and hand-held camcorders, the filmmaker-activists capture dramatic footage of clashes between average Egyptians calling for freedom and the repressive government forces attempting to stop them.

As co-director Karim El Hakim said after the film’s recent Sundance screening, “You can’t get any more cinema verité than this.”

Danish-Palestinian director Omar Shargawi and Egyptian-American director Karim El Hakim live with their families just a few blocks from Tahrir Square in Cairo. When hundreds of thousands of Egyptians take to the streets on January 25th, 2011 to demand the ouster of dictator Hosni Mubarak, Omar and Karim head down from their apartments to record the events. Viewers are immediately thrown into the visceral experience of the revolution. Crowds of protesters run through the streets shouting “Egypt! Egypt! “Join us! Join us!” “Freedom! Freedom!” When gangs of government-paid thugs and police start beating and shooting the protesters, the protesters shout “No violence! No violence!” This call to non-violence is one of the early strong points of the documentary. To emphasize the theme, Shargawi points out a crowd of demonstrators who surround a group of police yet refrain from assaulting them.

Danish-Palestinian director Omar Shargawi and Egyptian-American director Karim El Hakim live with their families just a few blocks from Tahrir Square in Cairo. When hundreds of thousands of Egyptians take to the streets on January 25th, 2011 to demand the ouster of dictator Hosni Mubarak, Omar and Karim head down from their apartments to record the events. Viewers are immediately thrown into the visceral experience of the revolution. Crowds of protesters run through the streets shouting “Egypt! Egypt! “Join us! Join us!” “Freedom! Freedom!” When gangs of government-paid thugs and police start beating and shooting the protesters, the protesters shout “No violence! No violence!” This call to non-violence is one of the early strong points of the documentary. To emphasize the theme, Shargawi points out a crowd of demonstrators who surround a group of police yet refrain from assaulting them.

Over time, though, these commendable calls to non-violence are drowned out by the tide of chaos and bloodshed that overtakes the demonstrations when the government attacks. Police fire into the roiling crowds of protesters with live ammunition, loud booms announce the launching of tear gas canisters through the air, and demonstrators and counter-demonstrators fight back and forth with truncheons, rocks, and knives. Demanding to see their passports, secret police harass Karim and Omar as they attempt to film the events, and Omar pulls a scarf around his face to disguise his identity.

Later, Karim is gassed in the face and stumbles home partially blinded, while Omar is severally beaten in a dark alley, barely emerging alive. Government snipers start shooting people through the windows of their apartments in the blocks around Tahrir Square – making viewers fear for the safety of the filmmakers in their own homes, particularly as one of them has a baby who keeps wandering close to the windows. Late in the film, government thugs even take over the street below the apartment building and start harassing the residents, which is what finally forces the filmmakers to question staying in the country.

In capturing the tumult of the Cairo protests, 1/2 Revolution depicts more violence than most Hollywood action movies – but tragically, the mayhem here is all too real.

The seemingly intractable rage captured in the film – both from democratic protesters righteously angry over the suppression of their human rights, and from entrenched government elites determined to hold on to power at any cost – highlights the central challenge facing the Egyptian people today. How will they overcome this bitterness and anger – these scars from decades of violence, repression, and authoritarian rule – in order to build a peaceful democracy?

In his seminal 1947 study of German film, From Caligari to Hitler, Siegfried Kracauer pointed out that the details of life captured in a film often reveal a country’s unconscious predilections. The details captured in 1/2 Revolution are ominous: activists repeatedly declare their willingness to die and become martyrs, the camera dwells on shattered heads and limbs, bodies on stretchers being rushed away, a man lifting up his shirt to show a bullet wound in his back, a pool of blood on the pavement with the word ‘Egypt’ traced in Arabic. Even more ominous are the anti-American and anti-Jewish symbols scrawled onto anti-Mubarak protest signs. One particularly ugly sign depicts Mubarak as the devil with pointy ears and a Star of David stamped on his forehead.

Sadly, the filmmakers and their friends engage in implicitly anti-Israeli rhetoric themselves. Co-director Omar Shargawi, whose father is Palestinian, says with pride of the demonstrations, “It was like being part of the intifada or something.” One of his friends, a woman also of Palestinian origin, expresses fears that “the Israeli army is massing at the border” and worries that the U.S. might invade. Given that Israel’s population of only 7.8 million is vastly outnumbered by Egypt’s population of 81 million, and given that the American government was generally supportive of the Egyptian revolution, these kind of fears come across as over the top. But this is the dark side of the revolution: the urge to look for blame in outside bogey-men – in this case, America and Israel – rather than look internally to ask why so many Arab states have failed to achieve lasting democracy. Continue reading LFM’s Govindini Murty at The Huffington Post and AOL-Moviefone: As Egypt Fights for Democracy, New Documentary 1/2 Revolution Goes to the Front Lines