[Editor’s Note: the post below appears today on the front page of The Huffington Post and AOL-Moviefone.]

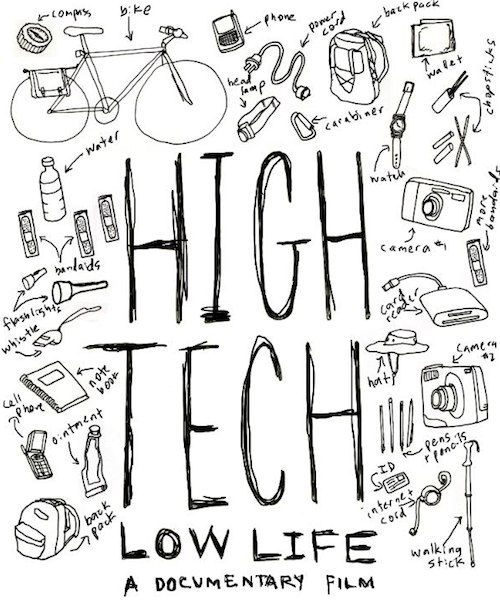

By Govindini Murty. Even as Chinese dissidents like Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo and artist Ai Weiwei suffer physical imprisonment, hundreds of millions of their fellow Chinese citizens are suffering a form of mental imprisonment thanks to their nation’s system of internet censorship. For example, the Chinese government recently blocked on-line searches for words relating to the 23rd anniversary of the June 4th, 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, censoring the terms “Tiananmen square,” “June 4th,” the number twenty-three, the words “never forget,” and even images of candles. The award-winning documentary High Tech, Low Life, currently screening at film festivals in the U.S., UK, and Australia, profiles two dissident Chinese bloggers who are working to challenge this Orwellian system.

Directed by Stephen Maing, High Tech, Low Life was in part funded by a Kickstarter campaign publicized on The Huffington Post and was an official selection of the 2012 Tribeca Film Festival. High Tech, Low Life documents the work of 57-year old blogger Zhang Shihe (known as “Tiger Temple”) and 27-year old Zhou Shuguang (known as “Zola”), two of China’s best-known “citizen reporters.” Even as the Chinese government uses internet technology to stifle dissent, these brave bloggers find creative ways to circumvent “The Great Firewall of China” and publish the truth about human rights abuses to the world. Along the way, Tiger and Zola suffer official harassment, familial disapproval, eviction, and arrest.

Blogger Zola describes in the film the vast apparatus of internet censorship that exists in China:

“There are 440 million netizens in China, 40,000 internal police monitor them, and 500,000 websites are blocked in China.” [Despite this,] “if an incident happens anywhere, netizens and citizen journalists will flock to the scene from all over the country. The censors might stop some of us, but they can’t stop all of us.”

Tiger Temple expands on the morally corrosive effect of the government’s censorship: “We’ve all been brainwashed. We’ve been listening to lies for too many years.” Although material prosperity may have improved in China, Tiger argues that life today is as bad as it was under Mao’s dictatorship. As Tiger puts it, the Chinese people are “complacent because they feel powerless.”

Tiger Temple and Zola could not be more different in style. The older, more experienced Tiger is a writer and former publisher living in Beijing who becomes closely involved in his subjects’ lives, bringing them food, money, and legal help. Tiger’s father was a high official in the Communist Party, but the family was persecuted by Mao during the Cultural Revolution in the ’60s. Tiger recalls how he and his family were beaten, evicted from their home, and exiled to the countryside. It was then, as a 13-year old, that Tiger says he started “roaming the country.”

Tiger Temple and Zola could not be more different in style. The older, more experienced Tiger is a writer and former publisher living in Beijing who becomes closely involved in his subjects’ lives, bringing them food, money, and legal help. Tiger’s father was a high official in the Communist Party, but the family was persecuted by Mao during the Cultural Revolution in the ’60s. Tiger recalls how he and his family were beaten, evicted from their home, and exiled to the countryside. It was then, as a 13-year old, that Tiger says he started “roaming the country.”

Tiger’s entry into blogging was almost accidental. Returning home one day from viewing an exhibition of Monet paintings in Beijing, he saw a woman being stabbed to death on the street by a man as bystanders watched. Horrified but unable to prevent the murder, Tiger grabbed his camera and documented its aftermath instead. He notes that when the police showed up, they were angrier at him for taking the photos than at the murderer himself, because such scenes would normally be censored from the press. Tiger went on to publish the photos online and caused a sensation, becoming known as China’s first “citizen journalist.” Tiger adds that he calls himself a “citizen” and not a “citizen journalist” because that way the government can’t ban him.

Years later, Tiger makes lengthy journeys on bike through the countryside to report on the lives of the rural poor who have suffered in the rush to urbanization. He is even on occasion tailed by agents of the government. In one trip documented in the film, Tiger bicycles 4000 miles to Er Loa, a village devastated by the illegal flooding of toxic waste by the local government. The floods of waste have caused the farmers’ homes to collapse and have made farming impossible. Villagers tell Tiger that local officials have warned them that if they complain too much they will be arrested. Not only does Tiger take photos and video of the environmental devastation, he also brings the villagers flour and noodles to feed them and tells them he has forwarded their information to a university in Beijing where law students are working to file a legal complaint with the authorities. Tiger interests an NGO in their case, and the farmers are ultimately brought to Beijing to speak at the Civil Society Watch’s Environmental Protection Conference.

Continue reading LFM’s Govindini Murty at The Huffington Post and AOL-Moviefone: “We’ve All Been Brainwashed”: China’s Dissident Bloggers Speak Out in High Tech, Low Life