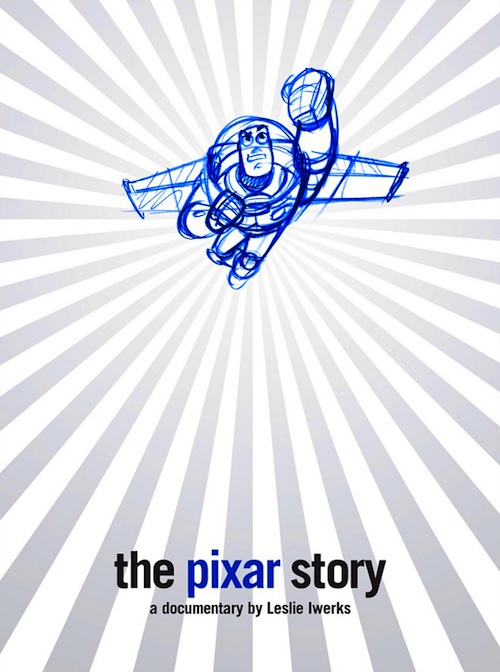

By David Ross. We all have a vague idea of the ‘Pixar story’: John Lasseter, Steve Jobs, technological innovations of some kind, fractious dealings with a decadent Disney, eventual world-wide success measured in billions of dollars and universal critical adulation. The 2008 documentary of the same name fills in the historical detail and provides human color.

By David Ross. We all have a vague idea of the ‘Pixar story’: John Lasseter, Steve Jobs, technological innovations of some kind, fractious dealings with a decadent Disney, eventual world-wide success measured in billions of dollars and universal critical adulation. The 2008 documentary of the same name fills in the historical detail and provides human color.

If the documentary itself is merely workmanlike, the story it narrates belongs amid the July 4th bunting of the American pageant. It’s a chapter in the tale of Graham Bell, Edison, the Wright Brothers, Disney, and Apollo 11, an episode in the cheerful reinvention of the world on the basis of something deep and generous in the American spirit. There’s very little for which contemporary Americans will not have to apologize to whatever god or superior alien race is watching, but Pixar speaks well of us. It mitigates just a little the malls and video games and rap music, everything we might, following Allen Ginsberg, call “Moloch.”

The Pixar Story is informative cultural history, but its implicit lessons have wider and more important application. For better and for worse, corporations now infiltrate every crevice of our culture, and it has become crucially important to weigh how corporatism and cultural meaning can be reconciled. Pixar represents a rare digital-age example of a corporation that’s deepened rather than debased the culture. The lessons are not particularly abstruse, but difficult to drive home and implement, viz.:

1) Corporations must construe themselves as communities rather than machines. Communities consist of autonomous and interactive people; machines consist of inanimate parts that exist in a paradoxical state of mutual dependency and complete isolation. Pixar resists the temptation to rationalize, regulate, and formalize presumably because those at the top – Lasseter et al. – are so free of the usual egomaniacal impulse to control and subsume. The result is an organization that’s supple, organic, and decentralized, as loose and yet unified as an eighteenth-century village. I imagine that Chuck Jones’ Warner Brothers team was much the same. Continue reading The Pixar Story & The Lessons of Pixar’s Success