By Patricia Ducey. Darren Aronofsky’s new film, Black Swan, is not The Red Shoes, the original ballet and madness movie that spawned many imitators – and it’s not a thriller (as it’s billed), either. It’s pretty clear early on that our heroine’s worst enemy is her own shaky self. Ballet movies like The Red Shoes and its progeny explore the Romantic ethos of the artistic life; to live, and perhaps even to die for art, is the highest calling of humanity – if we are to believe them.

By Patricia Ducey. Darren Aronofsky’s new film, Black Swan, is not The Red Shoes, the original ballet and madness movie that spawned many imitators – and it’s not a thriller (as it’s billed), either. It’s pretty clear early on that our heroine’s worst enemy is her own shaky self. Ballet movies like The Red Shoes and its progeny explore the Romantic ethos of the artistic life; to live, and perhaps even to die for art, is the highest calling of humanity – if we are to believe them.

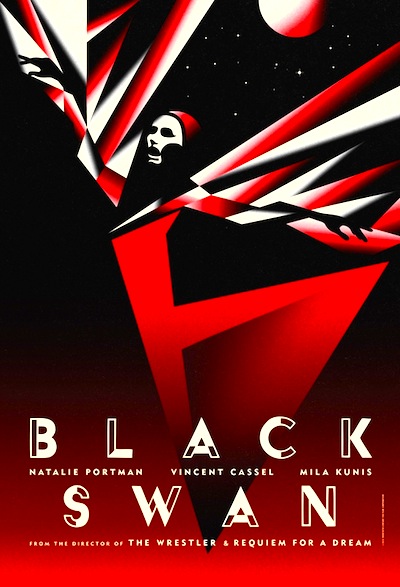

But Black Swan tosses dance aside. We never do understand why ballet is so important to our heroine Nina (Natalie Portman) or even to autocratic artistic director Thomas (Vincent Cassel). The dancing (even if I had not recently seen the electrifying Mao’s Last Dancer), is sadly pedestrian, even after Natalie Portman’s yearlong marathon of training. Aronofsky’s camera instead focuses mainly on the physical toll to the dancers’ bodies as they joylessly go through their paces. His characters never express dance as any sort of intellectual or spiritual vocation. They do not seek transcendence – they want to be stars! And our doomed ballerina Nina apparently suffers from the worst case of such careerism and perfectionism. We wonder for two hours whether she will make it to stardom, or whether her neuroses will destroy her main chance. This is not so much an opera as an after-school special – albeit R-rated -about self-esteem.

As in his previous films The Wrestler or Requiem for a Dream, Aronofsky eschews coherence or depth in his stories and instead uses narrative merely as a frame, as insubstantial as gossamer, on which to hang his feverish and sometimes arresting images. Tellingly, most of the images in Black Swan are not of the ballet itself but of sex (sex with a sadistic boss, in a dirty toilet, between lesbian rivals) and gore (flesh peeled off fingers, feet broken by dancing, guts ripped open by mirror shards).

With such explicit focus from the director on sex and death, what’s left for the actors to imply by nuance or expression? Not much. The arc-less script is not interested in nuance or emotional truth, and this hampers the performances of our two leads. Nina begins the movie as a tightly wound child and ends there, too – she is not destroyed by the dualities of the Black Swan/White Swan at all. She might just as well have been a lawyer or a housewife; the ballet is only a backdrop to foreground her neuroses.

Vincent Cassel does his best as the autocratic sexual-predator director (of course) who has no feeling or opinion on dance at all, and his character stays here as well. Thomas recites his leaden, James Cameron-style dialogue with as much brio as he can: “I don’t think you have it in you!” he bellows over and over to Nina. Yet he chooses her for the starring role anyway, because she shows “spirit.” The evening before, he clumsily and arrogantly attempts to kiss her and she bites his lip in a panic, drawing blood.

What is an actor to do with such nonsense?

The swan chorus, meanwhile, is a bunch of Mean Girls who sound like foul-mouthed high schoolers rather than skilled, focused artists. So Mila Kunis as Nina’s chief rival doesn’t take all this dance stuff so seriously, ya know? She can go out on the town, down some shots, a little blow, and show up fresh faced the next morning at rehearsal. Yet Thomas continually compares her nonchalance and resultant superior acting/dancing to Nina’s. Why doesn’t he then choose her then for the Swan? At least she’s interesting.

In Aronofsky’s Brutalist school of moviemaking, disgust is all: he despises his weak, needy characters. Why bother with love stories (Requiem) or families (Wrestler) or transcendent art, he seems to ask, since we’ll all be worms’ meat soon enough! In Black Swan he delivers another dollop of the old ultra-violence with close-ups of bleeding skin, broken limbs and even more broken mirrors – but this is more Petit then Grand Guignol: the gore in Black Swan exists for its own sake, completely uncoupled from dramatic context. With each gruesome image, he delivers pain and stimulation and little else; when the story slows down and Nina inspects her self-mutilation scars, you shut your eyes. In The Wrestler, at least, Mickey Rourke’s broken body served the narrative about his broken dreams.

Perhaps Aronofsky, the inveterate bombast, cannot identify with the constraint and tradition and nuance of the ballet aesthetic. To him, striving for the unattainable in love or art is masochism. What’s left for him, then, is merely a simplistic psychologizing of the Swan myth: the good Nina can’t handle her bad Nina. It remains a mystery, though, how this timorous child/woman could ever have risen to the top ranks of any company when her personality continually stunts her performances.

And so we wait for Nina’s inevitable disintegration – because we no longer expect happy endings from movies, and we’re not surprised when that inevitable disintegration comes. We simply passively wait for it – but this isn’t enough to sustain a long movie.

Aronofsky almost redeems himself in the end – too late, though, to save the film. Nina finally snaps and ‘becomes’ the Black Swan. She dances with all the vigor and sexual energy Thomas has been calling for. The camera follows her as she finally surrenders to her role and leaps out onto the stage, where she appears to molt her human identity and change into an actual living swan. She greets the increasing transformation of her body with joy and she dances, for once, with abandon, and she triumphs. As the camera silhouettes her final bow against the stage lights, the unity of image and psychology and story is simply breathtaking. What a movie this might have been, if Aronofsky had been half as rigorous for the preceding two hours.

There is hope, then, that this ambitious, reckless filmmaker will one day rise – like Nina – to live up to his own artistic potential.

[Footnote: My Christmas present from Hollywood was seeing the trailer for The Tree of Life, Terence Malick’s new film, which promises that in 2011 we will be treated to a film by an artist in full command of his many gifts, one who actually understands and respects the complexity of the human soul.]

Posted on December 13th, 2010 at 2:17pm.

I had my doubts about this movie from the start. They just do not have anyone who can play these roles anymore, and as you pointed out, they don’t really care about the art-form anyway. You said it – this is no “Red Shoes” or “Mao’s Last Dancer” (which I absolutely loved by the way).