By Patricia Ducey. Giacomo Puccini’s Wild West opera, La Fanciulla del West (“Golden Girl of the West”), is the latest offering from The Met: Live in HD series (Encore: Wednesday, January 26, 2011, 6:30 PST).

Commissioned 100 years ago by the Metropolitan Opera, Fanciulla is Puccini’s homage to the conventions and themes of the American Western—and to America itself. Puccini gave his patrons exactly what they were looking for, and after 19 standing curtain calls on opening night, the Met knew they had a durable hit in their first commission.

This year, the Met celebrates Fanciulla’s centenary with a boisterous, lyrical restaging featuring American soprano Deborah Voigt and Italian tenor Marcello Giordani and a delightful ensemble chorus of gunslingers, miners and banditos—a wonderful addition to a movie season that includes other shining examples of Americana like True Grit and the lesser Country Strong.

The music is Puccini-gorgeous, from one of his most beloved arias, “Ch’ella mi creda” (see here) sung by Dick Johnson as he begs his executioners to spare Minnie the knowledge of his perfidy, to the orchestral passages that reportedly inspired Andrew Lloyd-Weber’s Music of the Night.

Fanciulla’s story centers on frontierswoman Minnie, a saloon owner and Bible study teacher to a gold mining camp’s barely civilized miners. These are rough men: they drink their whiskey straight and shoot first, ask questions later. The only trace of sentiment emerges when they share stories of the dear mothers and big old dogs they left behind. Minnie and her “boys” are courageous loners, striking out for the fabled Sierra gold mines, for personal freedom and for adventure. Minnie with her book-learning and Bible lessons is the slim thread that ties them to civilization, and they are all in love in one fashion or the other with her. She helps them write home and tempers their anger in their many arguments and brawls. In one scene, when they catch one of their own cheating at poker, she instructs them, Bible in hand, “Every sinner can be redeemed.” Later, we suspect she will have to walk that talk herself.

In Minnie we have a new kind of Puccini heroine: a self-made woman, owner of a thriving business, cheerful in adversity and fiercely independent. Her pistol is her best friend, she recounts to an overly amorous miner, and she breaks up more than one unruly mob with a few well-aimed gunshot blasts. Puccini looks more to Annie Oakley than Mimi for this Minnie. She would rather live alone than be trapped in a loveless marriage with any of the several men in camp who endlessly woo her–as soon as she asserts that independence, though, in walks the handsome stranger. Of course she falls totally in love, but her love leads her to triumph here rather than to a pitiable death, as in most of Puccini’s other operas. In the final act, she singlehandedly holds back the lynch mob and at the same time inspires her man to renounce his banditry and dedicate his life to goodness and love.

In Fanciulla, Puccini weds the traditions of operatic tragedy with American optimism. Like the deservedly praised True Grit, Fanciulla exults in themes of Americana as well as in the Judeo-Christian heritage that anchors them. From True Grit’s Bible allusions–read without irony–to the rollicking barroom brawl in Fanciulla, both honor the eternal truths expressed by the Western genre and thus revive its classical expression. Puccini recognizes that the Western is the essential American morality play, and that goodness eventually will triumph in this land caught between wildness and civilization. That’s the real American Dream and the sense of possibility that drew so many of Puccini’s countrymen to our shores.

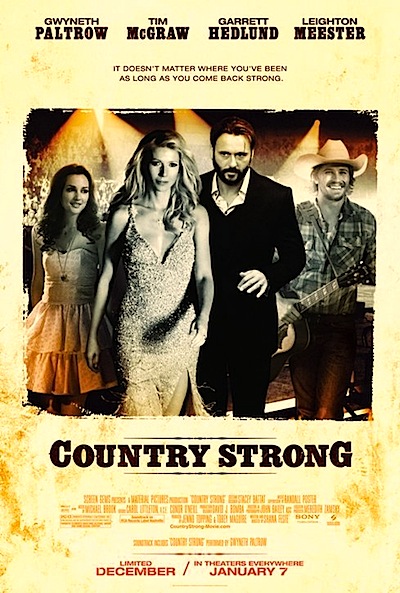

Writer/Director Shana Feste, on the other hand, is all mixed up about her Americana in Country Strong. She misses entirely the reason country music is so popular: there is no self-hating in Nashville. The movie starts out as a melodrama about Kelly Canter (Gwyneth Paltrow), a fading country singer sprung a little too early from rehab by her emotionally distant husband James (Tim McGraw) because … well, we’re never told why. He insists she needs to start touring before the docs release her. Do they need the money? Is he trying to gaslight Kelly because he loves a younger singer? We hope to find out, yet McGraw’s character and motivation remain a mystery.

Kelly wants rehab orderly Beau (who also conveniently happens to be a singer) to open for her on the tour, but James chooses newcomer Chiles Stanton (Leighton Meester) instead. Kelly is jealous of the younger woman and imagines her flirting with James—or maybe she is flirting with him?—yet Kelly herself has been bedding Beau since rehab. Who’s zoomin’ who? Eventually all four of them are on tour together, in the crucible of Kelly’s comeback. They hook up, break up, fight and make up, with lots of streaked mascara but little discernable rationale. With all possible plot points on the table, the histrionics and plot twists remain vaguely mystifying. No much is at stake here: not principles, life and death, nor even love. In hipster movies, love hurts.

Kelly wants rehab orderly Beau (who also conveniently happens to be a singer) to open for her on the tour, but James chooses newcomer Chiles Stanton (Leighton Meester) instead. Kelly is jealous of the younger woman and imagines her flirting with James—or maybe she is flirting with him?—yet Kelly herself has been bedding Beau since rehab. Who’s zoomin’ who? Eventually all four of them are on tour together, in the crucible of Kelly’s comeback. They hook up, break up, fight and make up, with lots of streaked mascara but little discernable rationale. With all possible plot points on the table, the histrionics and plot twists remain vaguely mystifying. No much is at stake here: not principles, life and death, nor even love. In hipster movies, love hurts.

The actors do a heroic job, and a few of the tunes, even though we never hear one in its entirety, are iPod worthy. Paltrow proves again what a rich, emotionally layered actor she is, and Meester, of Gossip Girl fame, wrests depth and nuance from a most shallow stereotype. Garrett Hedlund from Tron could have a singing career. Tim McGraw, one of the most radiantly masculine stars on screen, though, is seriously misused or underused. McGraw’s James is written as cold and distant, but this behavior is never explained. Maybe a prequel will explain his pinched rejection of the whole lot of them?

Country Strong is a serviceable enough musical melodrama, but it’s hard to tell what the point is. This is either a script-by-committee mashup, or Feste is another screenwriter gripped by existential confusion towards her subject. She cannot decide if Country Strong is a classic melodrama or hipster hit-piece. On the one hand, the script panders to the bien pensant with jabs at what she envisions as flyover country: Christians are hypocrites, patriots are jingoists, pro-lifers are haters, crossover country is insipid and beauty queens are stupid, etc. Then why is Kelly’s triumphant comeback song an insipid pop song itself, presented without irony? On the other hand, sometimes Country Strong seems to be playing it straight, as with the actors’ performances, and that does work. Her method seems to be to throw tropes and clichés on the wall, however contradictory, and see what sticks.

Puccini’s Minnie and the Coen brothers’ Mattie Ross would be perplexed at so much wild emotion in service of such small stakes. Minnie probably would chuck Kelly out of her saloon at the first whine, and Hattie would sniff and ride off, head held high, to right another wrong. They knew that their journey was the American journey, into the wilderness and into the human heart, and that “strong” is more than just a word in a song.

In related news, the inevitable: the Royal Opera House’s Carmen is soon to be released in 3D (see here). I’m down with that.

Posted on January 10th, 2011 at 3:56pm.