[Dr. Li-ling Hsiao, a longtime friend of Libertas, is Associate Professor and Assistant Chair of the Department of Asian Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This article appears in the 2010 issue of the Southeast Review of Asian Studies.]

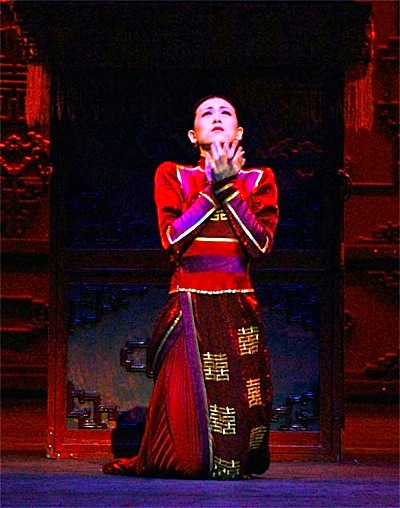

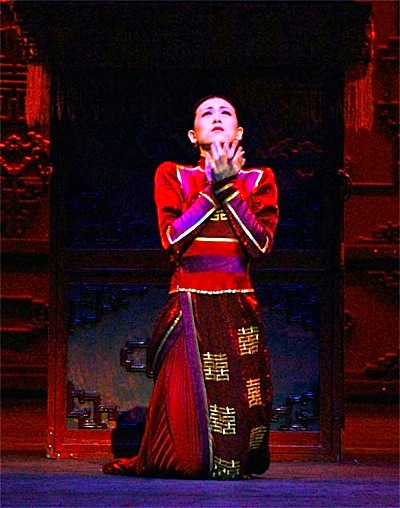

By Dr. Li-ling Hsiao. On a dimly lit stage, an old man lifts a cane and lights the red lanterns. Accompanied by the spare sound of ringing bells, the lanterns gradually rise like an ascending curtain and reveal a stage space for the dance of red lanterns performed by a corps de ballet dressed in blue. A female voice, singing in the style of the Peking opera, gradually becomes audible. This prelude opens Dahong denglong gaogao gua or, as it is better known in the West, Raise the Red Lantern. The performance combines elements of ballet, modern dance, and Peking opera. The conflation of East and West governs every creative aspect of the ballet, which explains why it has been acclaimed equally in China and throughout the world.

The ballet is the brainchild of Zhang Yimou (b. 1951), who made his name in the West as the director of the renowned Chinese film Raise the Red Lantern (1991). Zhang won the best director award at the Venice International Film Festival in 1991, and the film received an Academy Award nomination as best foreign film in 1992. Subsequent films like Shanghai Triad (1995), Hero (2002), House of Flying Daggers (2004), and Curse of the Golden Flower (2005) sealed Zhang’s reputation as a giant of world cinema, while his direction of the extravagant opening ceremony of the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing made him an international celebrity. Given his penchant for stunning visual pattern, Zhang’s interest in the highly stylized media of opera and ballet is hardly surprising. The ballet – his first – premiered in Beijing in 2001 and has since played in Europe and America. A revised version of the ballet, featuring the National Ballet of China, with music by Chen Qigang and choreography by Wang Xinpeng and Wang Yuanyuan, appeared on video in 2005, encouraging an assessment of what Zhang has both achieved and failed to achieve.

The ballet is the brainchild of Zhang Yimou (b. 1951), who made his name in the West as the director of the renowned Chinese film Raise the Red Lantern (1991). Zhang won the best director award at the Venice International Film Festival in 1991, and the film received an Academy Award nomination as best foreign film in 1992. Subsequent films like Shanghai Triad (1995), Hero (2002), House of Flying Daggers (2004), and Curse of the Golden Flower (2005) sealed Zhang’s reputation as a giant of world cinema, while his direction of the extravagant opening ceremony of the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing made him an international celebrity. Given his penchant for stunning visual pattern, Zhang’s interest in the highly stylized media of opera and ballet is hardly surprising. The ballet – his first – premiered in Beijing in 2001 and has since played in Europe and America. A revised version of the ballet, featuring the National Ballet of China, with music by Chen Qigang and choreography by Wang Xinpeng and Wang Yuanyuan, appeared on video in 2005, encouraging an assessment of what Zhang has both achieved and failed to achieve.

The story of the Red Lantern originates in a novella titled Wife and Concubines by Su Tong (b. 1963) published in 1990. Su Tong’s novella tells the story of a nineteen-year-old college student, Songlian, who marries into a rich household and becomes the fourth concubine of the much older master. The novella centers on the vicious competition and relentless jealousy governing the household world of the wives, concubines and maids, and on the friendship that develops between Songlian and the elder son of the master, Feipu, which verges on transgression. As these two plot lines progress, Songlian increasingly withdraws into solitude and self-confinement, while the abandoned well in which several concubines have died looms threateningly outside her room. Her attempt to distance herself from the intrigues of the household, however, does not prevent her from striking back after being slandered, resulting in the death of her maid and the loss of her master’s favor. After witnessing the adulterous third wife’s death by drowning in the well, Songlian loses her mind and becomes an invalid inmate of the household.

Zhang Yimou’s film brings a stunning visual aestheticism to Su’s story, while engaging in a significant plot revision. In the novella, Songlian attempts to remain above the petty intrigues of the household, but in the film she quickly succumbs to something devious and dark in her own nature and becomes as fully Machiavellian as the other women. The film thus assumes a moral and dramatic weight missing from the novella: Zhang’s Songlian is no mere innocent victim of circumstance, but a complex moral agent whose downfall is largely her own doing. In both novella and film, Songlian is the unintentional victimizer of the maid, but in the film she is the effective murderer of the third wife, whose infidelity she reports to the treacherous second wife, knowing, in some recess of her mind, that her tale is the death warrant of a competitor. Significantly, the novella envisions Songlian crazed by circumstance, while the film envisions her crazed by guilt. Zhang thus reconceives the story as a parable of the self caught in the fate it has created, and the film becomes a Shakespearean tragedy played out in a Chinese social context. The ingénue of the novella is no more; she has been replaced by the tragic heroine.

Zhang also accentuates the story’s symbolic elements, bringing a new complexity and intensity to the story. Most significantly, the film elevates the lantern, which the novella mentions only peripherally as a crucial leitmotif. In Zhang’s film, the lantern hangs in the courtyard of the lady with whom the master intends to spend the night. Fantasizing about being a wife or concubine, the maid, Yaner, raises her own red lantern, which provides Songlian with an excuse to mete out harsh punishment and unleash her own frustrations. She forces Yaner to kneel in the courtyard until the maid dies in the snow. Thus, the red lantern, an auspicious symbol, becomes a symbol of illicit desire and ambition as well as a morally ambiguous marker of the master’s favor. Zhang also makes an important symbol of the small hammers used to massage the feet of the wives and concubines. The massage, like the lantern, is a symbol of privilege, and the clicking sound of the hammer echoes throughout both the household and film, indicating the constant competition for favor. The sound of the hammer likewise has erotic connotations, suggesting the physical ministrations enjoyed by some but denied to others. Zhang brilliantly utilizes the symbolic elements to underscore the silent drama that plays out within the household; the symbolism allows Zhang to explore the intricacies of his domestic drama without impinging on the silence and the isolation that is its subtext. Finally, Zhang shifts symbolic emphasis from the well (a crucial motif of the novella) to a small stone room on the roof of the compound. Both symbolize the tragic fate of unfaithful women, but the room, situated above, suggests a totalitarian world of observation and control, and represents the panoptic eye of the master and his minions. Zhang achieves this effect by frequently adopting a rooftop perspective on the action below, taking in the stone room in what seems an incidental fashion. Visually, Zhang implants the room as a subconscious consideration and thereby prepares for its powerful revelation as a place of execution when the third wife is carried there, as if in funeral procession, at the end of the film. Zhang thus makes clever use of his actual location, the Qiao Compound in Pingyang, Shanxi Province, and turns an accidental feature of the structure – perhaps a harmless storage shed or recreational pavilion – into a haunting symbol of power and the dread of power.

Zhang also accentuates the story’s symbolic elements, bringing a new complexity and intensity to the story. Most significantly, the film elevates the lantern, which the novella mentions only peripherally as a crucial leitmotif. In Zhang’s film, the lantern hangs in the courtyard of the lady with whom the master intends to spend the night. Fantasizing about being a wife or concubine, the maid, Yaner, raises her own red lantern, which provides Songlian with an excuse to mete out harsh punishment and unleash her own frustrations. She forces Yaner to kneel in the courtyard until the maid dies in the snow. Thus, the red lantern, an auspicious symbol, becomes a symbol of illicit desire and ambition as well as a morally ambiguous marker of the master’s favor. Zhang also makes an important symbol of the small hammers used to massage the feet of the wives and concubines. The massage, like the lantern, is a symbol of privilege, and the clicking sound of the hammer echoes throughout both the household and film, indicating the constant competition for favor. The sound of the hammer likewise has erotic connotations, suggesting the physical ministrations enjoyed by some but denied to others. Zhang brilliantly utilizes the symbolic elements to underscore the silent drama that plays out within the household; the symbolism allows Zhang to explore the intricacies of his domestic drama without impinging on the silence and the isolation that is its subtext. Finally, Zhang shifts symbolic emphasis from the well (a crucial motif of the novella) to a small stone room on the roof of the compound. Both symbolize the tragic fate of unfaithful women, but the room, situated above, suggests a totalitarian world of observation and control, and represents the panoptic eye of the master and his minions. Zhang achieves this effect by frequently adopting a rooftop perspective on the action below, taking in the stone room in what seems an incidental fashion. Visually, Zhang implants the room as a subconscious consideration and thereby prepares for its powerful revelation as a place of execution when the third wife is carried there, as if in funeral procession, at the end of the film. Zhang thus makes clever use of his actual location, the Qiao Compound in Pingyang, Shanxi Province, and turns an accidental feature of the structure – perhaps a harmless storage shed or recreational pavilion – into a haunting symbol of power and the dread of power.

Continue reading Dancing the Red Lantern: Zhang Yimou’s Fusion of Western Ballet and Peking Opera