By Joe Bendel. Probably no division of the Academy Awards has more byzantine rules than the documentary wing. Their mandated seven day theatrical runs in both New York and Los Angeles can be difficult hurdles for nonfiction filmmakers to clear. However, every selection of the 2010 DocuWeeks will be officially Oscar eligible once they finish their week long runs at the ArcLight and IFC Film Centers. As is seemingly the case with every documentary series, this year’s DocuWeeks is a mixed bag, but two films in particular offer intriguingly intimate glimpses into lives of ordinary individuals living a world away from the arthouse cinema scene.

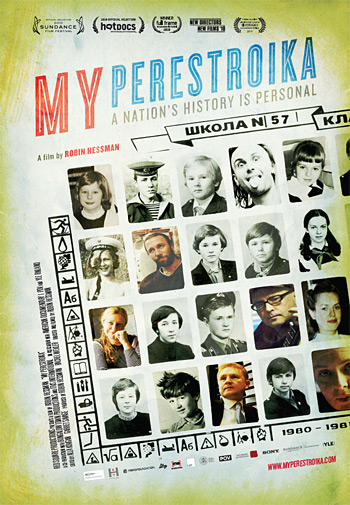

Even though he was badly hung-over, he knew there was a national crisis. Though the bleary-eyed Russian did not know at the time the hard-line Communist coup had deposed Mikhail Gorbachev, he saw that Swan Lake was the only program on television. For some reason, the Soviets always broadcasted the Tchaikovsky ballet during periods of internal turmoil. It is telling details like this that connect the personal to the grandly historical in Robin Hessman’s My Perestroika, which screened earlier this year at New Directors/New Films.

Even though he was badly hung-over, he knew there was a national crisis. Though the bleary-eyed Russian did not know at the time the hard-line Communist coup had deposed Mikhail Gorbachev, he saw that Swan Lake was the only program on television. For some reason, the Soviets always broadcasted the Tchaikovsky ballet during periods of internal turmoil. It is telling details like this that connect the personal to the grandly historical in Robin Hessman’s My Perestroika, which screened earlier this year at New Directors/New Films.

A Russophile in high school, Hessman was working for LENFILM, the Soviet film agency based in what was then Leningrad, at the time of the infamous coup. Through her time working and studying in Russia, Hessman developed a keen appreciation for the stoic nobility of average Russian citizens, which is clearly reflected in Perestroika. Using five former classmates as representative everymen, Hessman subjectively presents the last forty-some years of Russian and Soviet history through their reminiscences and home movies.

Yes, there is a certain nostalgia for their childhood years lived under the yoke of Soviet tyranny. However, they are really wistful for their lost innocence rather than the supposed virtues of the Brezhnev era. As becomes clear in their interviews, as the Perestroika generation came of age, it also became quickly disillusioned.

Still, not all of the film’s lead voices are doing badly. An entrepreneur with a small chain of high-end men’s clothing stores, Andrei has done quite well for himself. He is also the most vocal critic of the current Putin regime. While none of the five have led exceptional lives, Hessman had the good fortune to find participants who had been somewhat in the vicinity of great events. Indeed, the experiences of Perestroika’s subjects defy easy classification, at various times lending credence to wide array of political interpretations (though it is hard to find much in the film to justify any faith in Putin’s puppet government).

—

Tibet is also changing drastically, which is exactly what China wants. For instance, it has become increasingly difficult for Tibetans not fluent in Chinese to conduct business transactions. Such are the challenges facing a young nomadic family in Tibet’s eastern Kham region as presented in Summer Pastures, an intimate new documentary from Lynn True and Nelson Walker (with co-director Tsering Perlo), also currently screening as part of DocuWeeks LA.

In many ways, Locho and Yama are much like any other parents you would find anywhere else on Earth. Their greatest hope is for their daughter to have greater opportunities in her life than have been available for them. However, their daily chores are far removed from those western audiences will be familiar with, including the daily spreading and drying of manure for fuel that starts Yama’s daily routine. It is a hardscrabble life, but it is what they have always known.

Unfortunately, it is not clear whether the nomads’ way of life will be sustainable much longer. Inflation constantly drives up the price of their supplies, while they seem to have less to show for their labors. Adding further uncertainty, Yama suffers from a persistent heart ailment, yet she keeps working like an ox – in contrast to Locho, who often seems like an overgrown kid herding their livestock.

Unfortunately, it is not clear whether the nomads’ way of life will be sustainable much longer. Inflation constantly drives up the price of their supplies, while they seem to have less to show for their labors. Adding further uncertainty, Yama suffers from a persistent heart ailment, yet she keeps working like an ox – in contrast to Locho, who often seems like an overgrown kid herding their livestock.

Even in their remote corner of Tibet, Locho and Yama feel the impact of great macro forces. However, True and Walker focus their sites on their deeply personal family drama, (somewhat timidly avoiding the occupying Chinese elephant in the room). Yet by conveying such a strong sense of the nomadic couple’s personalities and relationship dynamics, Pasture will have most viewers rooting for this family as the film unfolds.

Pasture forgoes filmmaker commentary, instead capturing the nomads’ lives unfiltered, in a style not incompatible with that of Digital Generation Chinese independent filmmakers. Though it requires some patience, it is certainly rewarding to meet Yama and Locho, whose spirit and resiliency the filmmakers capture quite vividly. Both Pasture and Perestroika are difficult films to pigeon hole, but they have more merit than most docs released this year. They are currently screening in Los Angeles, as DocuWeeks continues at the ArcLight.

Posted on August 9th, 2010 at 9:32am.