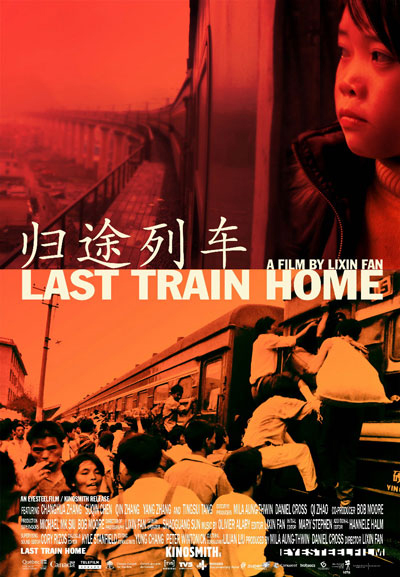

By Joe Bendel. Whether you consider it an unintentional disconnect stemming from China’s rapid industrialization or outright hypocrisy, the chasm between official rhetoric and reality is wide and stark in the Communist People’s Republic of China. It might be go-go times in the big coastal commercial centers, but the rural areas are desperately poor. An estimated 130 million migrant workers leave for those cities, working long hours for exploitative wages. They only make one annual return home for the traditional New Year holiday. Considered the world’s largest migration of people, documentarian Lixin Fan examines the taxing ritual through the eyes of one struggling Chinese family in Last Train Home, which opened Friday in select theaters nationwide.

Zhang Changhua and Chen Suqin are second class citizens, veritable illegal aliens within their own countries. Under the government’s restrictive residency laws, they have few formal rights and no access to social services outside their home district. Yet, they have had little choice but to seek work in China’s teeming urban centers. As a result, they have rarely seen the pre-teen daughter and young son they left to be raised by their grandmother.

Zhang Changhua and Chen Suqin are second class citizens, veritable illegal aliens within their own countries. Under the government’s restrictive residency laws, they have few formal rights and no access to social services outside their home district. Yet, they have had little choice but to seek work in China’s teeming urban centers. As a result, they have rarely seen the pre-teen daughter and young son they left to be raised by their grandmother.

Mother-daughter relationships can be difficult even under easier circumstances, but the three years Chen and her daughter Zhang Qin have been separated are taking a toll. Yet Chen cannot entirely blame her for feeling abandoned, even while lamenting that she has not been a good mother. Unfortunately, the resentful daughter spitefully drops out of school, becoming a migrant worker herself. It is a bitter turn of events for her parents, who now must face the possibility that many of their sacrifices will have been for naught. They also know only too well the rough education she is in for, especially when navigating the yearly mass exodus.

Sharing an obvious stylistic affinity with the Digital Generation of independent Chinese filmmakers, Chinese-Canadian director Lixin Fan is not afraid of holding long, quiet shots. However, he captured some uncomfortably intimate family drama, while conscientiously refraining from adding outside commentary. Clearly, the filmmaker built up a large reservoir of trust with his subjects. In return, he lets them speak for themselves in their own words, unfiltered and unhurried.

Train is a very personal film, but it is hard to miss the underlying point that approximately 130 million more migrant Chinese workers currently endure similar conditions. Ironically, China’s peasants used to be the PRC’s politically privileged class, but now the laws are rigged against them.

Should digital auteur Jia Zhangke ever remake John Hughes’ Planes, Trains, and Automobiles, it would probably look a lot like this. An unvarnished exercise in cinema vérité that takes on tragic dimensions, Train is a pointed corrective to the uncritical media coverage the Chinese government carefully cultivates. It is all the more difficult to shake, since it is not at all clear everything will ultimately work out alright for the Zhang family. Indeed, such is the nature of life. Uncompromising but deeply humanistic, Train opened last week in select theaters nationwide.

Posted on September 2nd, 2010 at 9:53am.