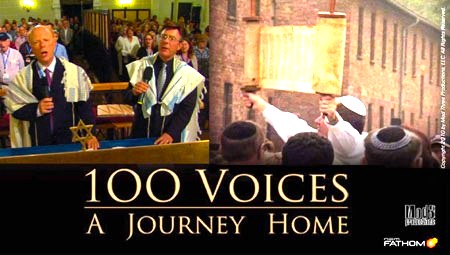

By Joe Bendel. There were more righteous gentiles from Poland than any other country. No strangers to suffering, three million Poles also died under National Socialism, while the Polish resistance forces were the only organized underground with a division specifically dedicated to saving Jewish lives. Yet, the Nazis were grimly successful cleaving apart Polish and Jewish culture, though they had been closely intertwined for centuries. In an effort to mend that breach, a group of 72 cantors made an emotional tour of Poland last June, fortuitously captured in Danny Gold and Matthew Asner’s documentary 100 Voices: A Journey Home, which began a limited engagement in New York and Los Angeles last Wednesday, following a special nationwide one-night event-screening this past Tuesday.

Tuesday’s special screening was presented under the auspices of NCM Fathom, the in-theater event specialists, which is particularly apt considering their specialty simulcasting opera. Indeed, there is a strong affinity between opera and the cantorial music of Voices. In fact, the father of two tour participants probably saved his life during the Holocaust by convincing the Nazis he was an opera singer rather than a cantor. While their music is liturgical, most cantors’ delivery is expressive and dramatic, bearing a strong stylistic resemblance to full-voiced opera singing.

After providing viewers an essential grounding in cantorial music and great cantors past (including the jazz-influenced Moishe Oysher), Voices follows the cantors on their eventful tour, organized by the forceful Cantor Nathan Lam of the Stephen S. Wise Temple in Los Angeles. Adding additional tragic significance, Polish President Lech Kaczyński was in attendance for their tour-opening command performance at Warsaw’s National Opera House mere weeks before his fatal plane-crash. It was a heavy program featuring an original composition penned by Charles Fox (probably best known for “Killing Me Softly”) inspired by Pope John Paul II’s simple prayer left at the Western Wall.

After providing viewers an essential grounding in cantorial music and great cantors past (including the jazz-influenced Moishe Oysher), Voices follows the cantors on their eventful tour, organized by the forceful Cantor Nathan Lam of the Stephen S. Wise Temple in Los Angeles. Adding additional tragic significance, Polish President Lech Kaczyński was in attendance for their tour-opening command performance at Warsaw’s National Opera House mere weeks before his fatal plane-crash. It was a heavy program featuring an original composition penned by Charles Fox (probably best known for “Killing Me Softly”) inspired by Pope John Paul II’s simple prayer left at the Western Wall.

Yet, the next performances were probably even more personally moving for the cantors, including memorial performances at Warsaw’s only surviving synagogue and at the gates of the Auschwitz concentration camp. However, the tour ended on a hopefully note, culminating with an open-air concert at the Krakow Jewish Cultural Festival, organized by the Catholic Janusz Makuch. Embracing the term “Shabbos goy” Makuch has worked to foster an appreciation of Poland’s Jewish heritage since 1988 (an effort greatly aided by the fall of Communism in 1989).

While the music of Voices may not be to all tastes, precisely for its operatic quality, there is no denying its power. Beautifully recorded and presented by directors Gold and Asner with cinematographers Jeff Alred and Anthony Melfi, it should lead to a deeper and wider appreciative of cantorial music, certainly outside Judaism and perhaps within the faith as well.

Indeed, Cantor Lam’s project was notable not just for the size of the tour, but the noble intent. Recently, many religious leaders have acted provocatively, even insensitively, while claiming the mantle of intolerance (yes, I definitely mean the organizers of the World Trade Center mosque here). However, the Voices tour really was undertaken in the spirit of tolerance, seeking to strengthen ties and understanding between faiths and people. A well intentioned film executed with grace and dignity, Voices deserves an audience well past Oscar season. It plays in select theaters in New York and Los Angeles through September 28th.

Posted on September 26th, 2010 at 12:08m.