By Joe Bendel. To be fair, the evangelical film industry here in America is still in its infancy, but it would behoove Christian filmmakers to look to Finland for inspiration. Submitted last year as the Scandinavian country’s official foreign language Oscar contender, themes of Christian faith and redemption are front and center in Klaus Hӓrö’s Letters to Father Jacob, which opened this Friday in New York. [See the trailer here.]

As Letters begins, one might think it’s a film noir. About to be released on a pardon she never requested, the hardboiled Leila Sten does not want anyone’s help. Yet as the dramatically lit prison official explains, a compassionate retired priest has offered her a job helping with his correspondence. Blind but profoundly devout, Father Jacob receives letters asking for his prayers from spiritually ailing people around the country. At least, he does until Leila arrives.

Naturally, his simple piety and do-gooder mentality initially irk the callous Leila, even though the depth of his faith and commitment are unimpeachable. The film builds towards a redemptive crescendo of reconciliation, but director Hӓrö never engages in cheap theatrics along the way. Instead, Leila’s gradual change of heart culminates in a relatively quiet, but truly honest pay-off.

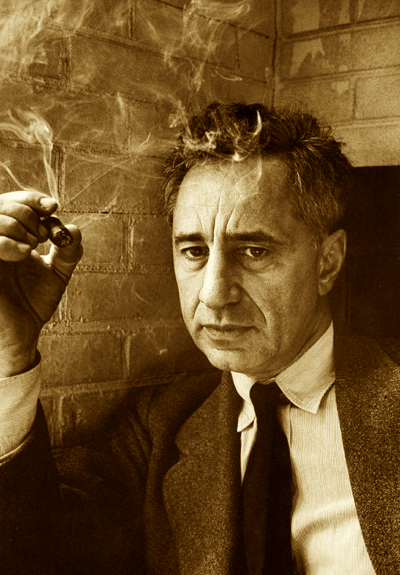

As the title Father, Heikki Nousiainen truly transcends the shopworn kindly old country priest stereotypes with a performance of genuine pathos and humanity. Though it is a less showy role, Kaarina Hazard is quite accomplished as the surly Sten, deftly delivering the film’s emotional knockout punch. Indeed, they both have the look of real flesh-and-blood people who have seen a lot of life’s pain and struggles.

Like recent evangelical films, Letters is a deeply religious work – yet as cinema, it is fundamentally character driven. It is also not afraid to look into the darkness and doubts lingering in its characters’ souls. Hӓrö helms with a sensitive touch throughout, exhibiting tremendous sympathy for the polar opposite protagonists. A handsome production, Tuomo Hutri’s warm cinematography strikingly captures the verdant surrounding environment while Kaisa Mӓkinen’s sets look dank yet appropriately sheltering.

Deceptively simple, Letters is a subtly powerful film. Elegantly crafted and legitimately moving, it is definitely recommended to all art-house cinema patrons not already too cynical to appreciate its sincerity. It is now playing in New York at the Cinema Village, and will expand to Los Angeles this week.

Posted on October 11th, 2010 at 11:45am.