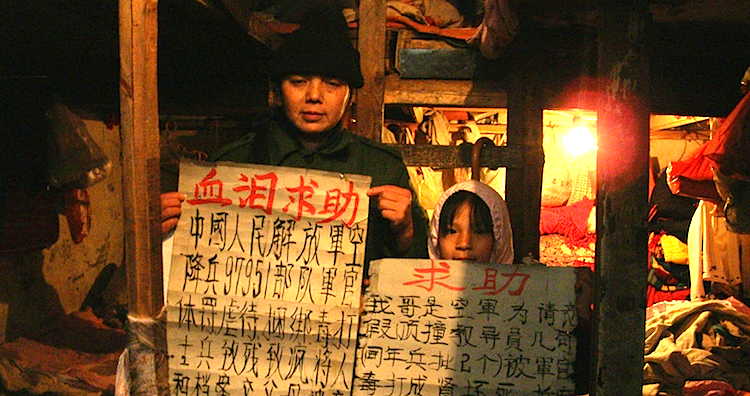

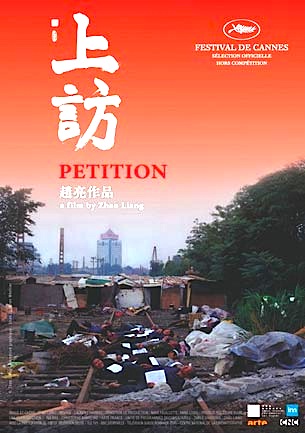

By Joe Bendel. Imagine the Keystone Cops with a severe mean streak. That is pretty much what you get from the Chinese military police stationed in a hardscrabble village on the North Korean border. Watching a full day of these officers on the job is not a pretty picture, but it is often quite absurd. Such is the nature of Chinese criminal justice subversively documented by Zhao Liang in Crime and Punishment (trailer above), which screens at the Anthology Film Archives in conjunction with the long-awaited theatrical release of Zhao’s devastating Petition.

Distributed by dGenerate Films, the specialists in independent Chinese cinema, Punishment watches fly-on-the-wall style as the recruits of the People’s Armed Police (PAP) gruffly patrol the isolated border town in hopes of a more permanent and prestigious assignment at the end of their two year tours. Essentially temps, the young men do not seem to be concerned with forging any rapport with the locals. Beatings are pretty much par for the course, as the soldiers quickly demonstrate during their first case of the day.

A severely hard-of-hearing man is hauled in on suspicion of stealing a cell-phone, with the obvious irony therein completely lost on the PAP. When their interrogation flounders, they first resort to public humiliation, eventually falling back on a good old-fashioned beating. “Turn off the cameras” they instruct Zhao. We will be hearing those words several times more before the film ends.

A severely hard-of-hearing man is hauled in on suspicion of stealing a cell-phone, with the obvious irony therein completely lost on the PAP. When their interrogation flounders, they first resort to public humiliation, eventually falling back on a good old-fashioned beating. “Turn off the cameras” they instruct Zhao. We will be hearing those words several times more before the film ends.

Although they do not physically assault the subject of their next investigation, their behavior towards a dirt poor farmer collecting scrap metal without a dozen government permits filed in triplicate is arguably crueler. Watching them badger and berate the clueless old man feels like one of the longest, most uncomfortable sequences ever captured on film.

As the day progresses, it looks like the coppers might be doing some legitimate police work when they launch a manhunt for a suspected killer. However, the only prey we see them bag is a desperate farmer poaching firewood to sell for New Year’s gifts for his children. Even the arresting officers have misgivings after seeing the suspect’s truly mean living conditions. Unfortunately, they had already administered the requite beat-down by this point.

Although Zhao basically cuts the camera when he is told, he still leaves no question as to the nature of what happens shortly thereafter. Like most Digital Generation filmmakers, Zhao eschews artificial conventions like voice-over narration and talking head interview segments. Aside from a few Dragnet like title cards explaining what happened to suspects after their questioning/thrashing, Zhao simply captures the scene in his lens, letting each character speak for himself through his behavior.

While Punishment does not have the same emotional heft as Petition, it is still a rather shocking expose of the Chinese criminal justice system. Yet, for all the abuse and intimidation meted out by the PAP, their actual results are less than impressive. After three investigations and much thuggery, they have less than one thousand Yuan in fines to show for their efforts. Daring in its own right, the unvarnished Punishment is definitely worth seeing when it screens at Anthology Film Archives Saturday (1/15) and Sunday (1/16) in conjunction with Zhao’s staggering Petition.

Posted on January 14th, 2011 at 6:48pm.