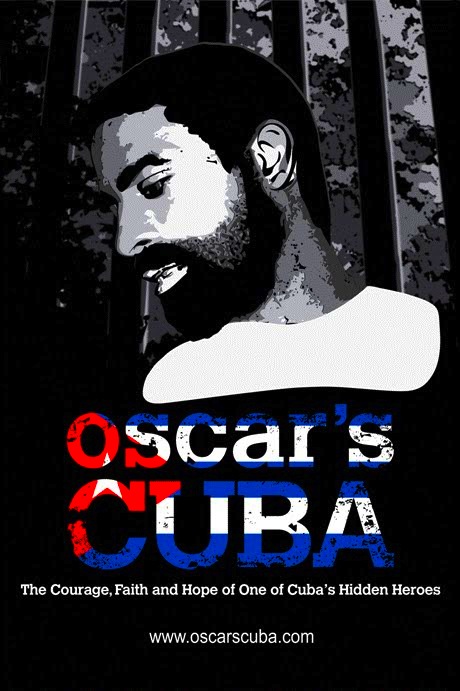

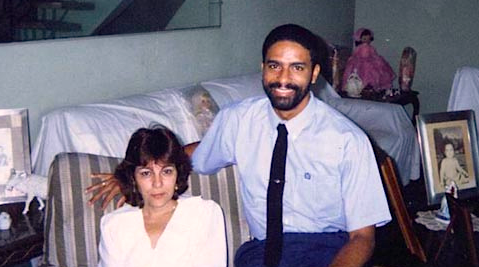

By Joe Bendel. It is not hard to see why the Castro brothers fear Dr. Oscar Elías Biscet. A medical doctor with commanding leading man looks, Dr. Biscet has been a selfless and tireless champion of human rights in Cuba. In short, he is everything they are not, which would make him a formidable political rival if Cuba were a free democracy.

Of course, this is not the case. Imprisoned for years, usually in solitary confinement, Dr. Biscet has become a unifying symbol of hope and non-violent resistance throughout the island gulag, as filmmaker Jordan Allott documents in Oscar’s Cuba, a selection of the 2011 John Paul II Film Festival, which has a special screening this coming Wednesday in Las Vegas at the Clark County Library Theatre.

When allowed her brief bi-monthly visit, Dr. Biscet’s wife Elsa Morejon always brings him toilet paper, because his Communist captors refuse to supply such everyday staples necessary for basic human dignity. This ritual encapsulates the essence of the Cuban police state. However, it has not broken Dr. Biscet’s spirit according to those who have met him in prison. No stranger to Castro’s dungeons, thirty-six days after serving a three year prison sentence, Biscet was swept up again in the notorious 2003 Black Spring round-up of seventy-five Cuban dissidents. To this day, he remains in a dark, confined, unsanitary cell.

When allowed her brief bi-monthly visit, Dr. Biscet’s wife Elsa Morejon always brings him toilet paper, because his Communist captors refuse to supply such everyday staples necessary for basic human dignity. This ritual encapsulates the essence of the Cuban police state. However, it has not broken Dr. Biscet’s spirit according to those who have met him in prison. No stranger to Castro’s dungeons, thirty-six days after serving a three year prison sentence, Biscet was swept up again in the notorious 2003 Black Spring round-up of seventy-five Cuban dissidents. To this day, he remains in a dark, confined, unsanitary cell.

Born shortly after the unsuccessful Bay of Pigs invasion, Biscet has lived his entire life under Castro’s regime. Yet, the dissident doctor has always maintained a profound Christian faith. In fact, much of the pro-life Biscet’s activism began in protest of the Communist government’s policies of forced abortions – and even infanticide – of premature newborns to bolster their internationally vaunted infant mortality statistics. He would become Cuba’s leading advocate of democratic reform and a proponent of non-violence, often referencing the works of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Henry David Thoreau.

Though not able to talk to the man himself (for obvious reasons), Allott interviews many of Biscet’s former prison-mates and fellow human rights activists, without the sanction or supervision of the Cuban regime. We also hear from former Cuban political prisoner and U.S. Ambassador (to the UN Commission on Human Rights) Armando Valladares, a figure well worthy of his own documentary.

While clearly produced to spur grassroots activism, Allott still earns props for his on-the-spot undercover reporting, capturing first-hand the unsavory realities of Cuban life, like Castro’s thuggish flash-mobs sent to intimidate dissidents and their families. Jazz and Afro-Cuban music lovers will also appreciate the original score composed by bandleader-defector Arturo Sandoval, Dizzy Gillespie’s close collaborator and heir as the king of the trumpet’s uppermost registers.

Far too much of Oscar’s Cuba will come as a revelation to general audiences who rely on the absentee media for international news. Highly informative, but also an inspiring portrait of one man’s faith, courage, and dignity in the face of oppression, Oscar’s Cuba was a truly fitting selection for the JP2FF. Recommended along with a prayer for Dr. Biscet and his colleagues, Oscar’s Cuba screens this coming Wednesday (3/2) in Vegas.

Posted on February 25th, 2011 at 4:37pm.