WORLD OF TOMORROW : Teaser trailer from don hertzfeldt on Vimeo.

By Joe Bendel. One thing animation always does better than live action is showing the world from a radically different perspective. Some of the films selected for Ron Diamond’s annual curated animation showcase take viewers into space and eons into the future. Others give us fresh terrestrial vantage points. Although necessarily uneven, the highs of this year’s program are particularly lofty because it includes one of the few short films that has racked up more reviews and accolades than most features, Don Hertzfeldt’s thought-provoking World of Tomorrow. Space and time travelers lead the way in the 17th Annual Animation Show of Shows, which screens this Thursday in Los Angeles.

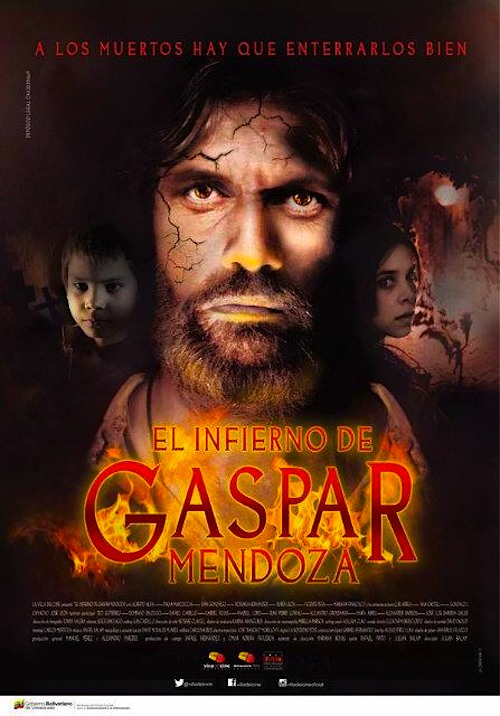

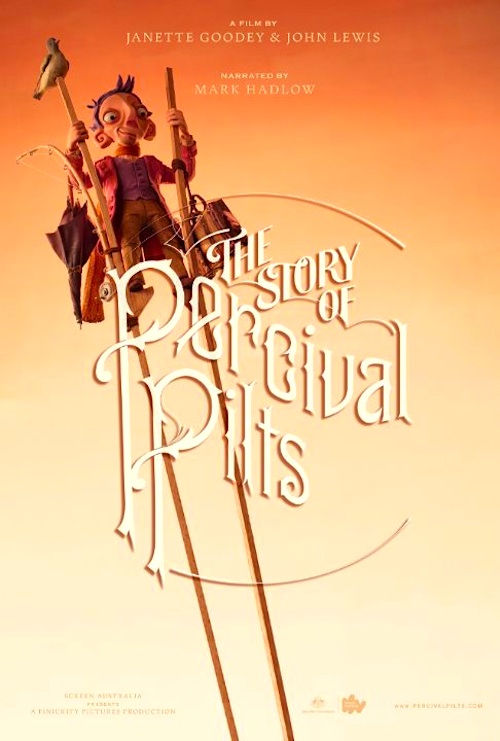

Wisely, the really big show starts with one of the best selections, but rather than an exercise in future speculation, Janette Goodey & John Lewis’s The Story of Percival Pits is a wonderfully old fashioned fable. Employing unusually elegant stop-motion animation, it tells the tall tale of a boy who decides to live his life entirely on stilts. As he matures into a man, he recommits himself to the stilt life, building them ever higher to the point he can no longer partake of human society. It is sort of a sad story, but also somewhat Promethean, narrated with appropriate sensitivity by Mark Hadlow.

Wisely, the really big show starts with one of the best selections, but rather than an exercise in future speculation, Janette Goodey & John Lewis’s The Story of Percival Pits is a wonderfully old fashioned fable. Employing unusually elegant stop-motion animation, it tells the tall tale of a boy who decides to live his life entirely on stilts. As he matures into a man, he recommits himself to the stilt life, building them ever higher to the point he can no longer partake of human society. It is sort of a sad story, but also somewhat Promethean, narrated with appropriate sensitivity by Mark Hadlow.

In comparison, Tant de Forets, Geoffrey Godet & Burcu Sankur’s rendering of Jacques Prévert’s deforestation verse feels like mere filler. Likewise, Conor Whelan’s Snowfall is also decidedly small in scope, introspectively examining a gay man’s emotional response when he is “rejected” by a straight man with whom he thought he was clicking. That would be fine subject, indeed one that is rarely addressed, but the computer animated characters are not very expressive.

However, it is followed by Lynn Tomlinson’s Ballad of Holland Island House, one the most aesthetically adventurous films in the Show of Shows. Using oil-based clay, it follows the rising waters encroaching on an abandoned Chesapeake island house, while accompanied by a haunting sea chanty. Stylistically, Amanda Palmer & Avi Ofer’s Behind the Trees is also somewhat abstract, but it is basically just a short punchline of a film constructed around the slightly nutty things Palmer’s husband says when he is half-asleep that so charm her.

With Konstantin Bronzit’s We Can’t Live Without Cosmos, we finally reach what could be considered the centerpiece of the Show of Shows. It is an increasingly surreal ode to friendship and meditation on loss, focusing on two cosmonauts training for the next big launch. Our POV characters are the class of their class, but it is a one-man rocket. That leaves the second place finisher to watch in horror as the alternate, when tragedy strikes the mission. Cosmos has a retro-Soviet Star City look, yet some of his imagery is still surprisingly haunting. Ultimately, the mysterious trumps all the cold antiseptic hardware. Believe it or not, it would fit well thematically programmed with Kubrick’s 2001: a Space Odyssey.

Although not as high concept, Isabel Favez’s Messages Dans L’Air proves old animation staples like cats looking to scarf down an unsuspecting fishbowl inhabitant still work when executed with wit and style. It is refreshingly old school, even if the pastels are modern. It is also quite funny.

Iranian sibling filmmakers Babak & Behnoud Nekooei seem to invite allegorical interpretation for Stripy, which celebrates the nonconformist impulses of a worker drone tasked with painting straight barcode lines in a box factory. Even though they not so surprisingly avoid any mention of politics in their biographical vignette, any form of dissent in Iranian cinema is a worthy development. It is also visually striking and upbeat, like an unambiguously optimistic Brazil, accompanied by Brahms’ Hungarian Dance No. 5.

Unfortunately, Ascension just doesn’t work, but Melissa Johnson & Robertino Zambrano’s Love in the Time of March Madness, an autobiographical account of life as a very tall, former basketball playing woman has a lot of heart. Shrewdly, Hertzfeldt’s World of Tomorrow concludes the Show of Shows, because it is a tough act to follow, earning mention alongside the likes of H.G. Wells and Olaf Stapledon. Check out a full review here.

There are more than enough substantial and satisfying films to carry this year’s Show of Shows, especially if you have not yet seen World of Tomorrow at Sundance or via vimeo VOD. We Can’t Live Without Cosmos is a worthy companion film in terms of ambition and intelligence. The Story of Percival Pots and Stripy also have some heft to them and they look terrific. Animation fans really need to catch up with all four, so the 17th Annual Animated Show of Shows is convenient opportunity to do so. It screens this Thursday (9/24) at the Arclight in Los Angeles and October 5th at the Spectrum 8 in Albany, with more cities announced here.

Posted on September 23rd, 2015 at 11:34pm.