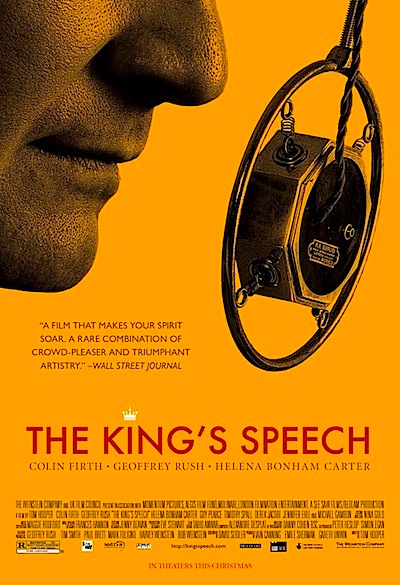

By Govindini Murty. The King’s Speech is that surprising thing – a film that glorifies the British monarchy while at the same time espousing American-style democratic principles. A warm-hearted, sumptuously-mounted film directed by Tom Hooper, The King’s Speech is the sort of feel-good drama that is likely to please Academy voters on Oscar night tonight and earn it a number of top prizes. In particular Colin Firth, who gives a fine, career-defining performance as King George VI, looks likely to take home the Best Actor honor.

By Govindini Murty. The King’s Speech is that surprising thing – a film that glorifies the British monarchy while at the same time espousing American-style democratic principles. A warm-hearted, sumptuously-mounted film directed by Tom Hooper, The King’s Speech is the sort of feel-good drama that is likely to please Academy voters on Oscar night tonight and earn it a number of top prizes. In particular Colin Firth, who gives a fine, career-defining performance as King George VI, looks likely to take home the Best Actor honor.

The King’s Speech tells the story of King George VI of Great Britain (the father of the current Queen Elizabeth II) and his struggles to overcome a speech impediment in the years leading up to his ascension as King. What gives this struggle its greater relevance is that George VI is part of a generation of royals in the 1920’s and ’30s who must learn to communicate in the new mass media of radio and film at the very time that dangerous totalitarian demagogues were using those mediums to threaten Western civilization. (The film highlights the double-edged implications of these new mass media when it describes, for example, the wireless radio as “a Pandora’s box.”) Oddly enough, it will be constitutional monarchs like George VI who, lacking any real political power, will instead function as the symbolic representatives of the people (an echo of the Hobbesian idea that the king is created by the covenant of the people), to articulate to them their nation’s support for freedom and democracy against tyrants like Stalin and Hitler who were working to wipe those freedoms out. As George VI says in the film as he readies to speak at the outbreak of war in 1939: “The nation believes that when I speak, I speak for them.”

The King’s Speech opens in 1925 with Prince Albert, the Duke of York (the future George VI), preparing to give a speech at the close of the British Empire Exhibition games. The Duke struggles tortuously through his speech, barely able to get even one sentence out. His wife Elizabeth, the Duchess of York (played with warmth and wit by one of my favorite actresses, Helena Bonham-Carter) looks on with pained love and dismay. As the story unfolds, Elizabeth brings speech doctors to Albert, but none of them work out and the Duke gives up the effort out of frustration. Compounding the problem, Albert’s father, the aging King George V (played by Michael Gambon), is dismissive of Albert’s struggle to speak and has repeatedly thrown him into public situations where he is forced to give speeches before large crowds. Albert’s older brother, Edward, the Prince of Wales (played by the nervy, angular Guy Pearce), is verbally articulate, but is a playboy who would rather romance married women than attend to his duties as the future king. Edward routinely mocks Albert’s speech impediment, only making his brother’s torment worse.

Out of desperation, Elizabeth goes to an unorthodox speech therapist, Lionel Logue, played with intelligence and impishness by Geoffrey Rush. Logue is a far cry from the genteel, expensive doctors the Duke and Duchess have been used to. His office is in a ramshackle old building in an unfashionable part of London, and he lacks even a doctor’s degree. However, Logue has the warmth and humanity – and the unorthodox teaching methods – to break through Albert’s icy shell of pride, pain, and frustration. Elizabeth persuades Albert to see Logue, and in a series of encounters – including their first one in which Logue democratically insists to Albert that they call each other by their first names, and that in his consulting room “we’re equals” – Logue works on Albert step by step to speak more clearly.

Logue may lack a serious medical pedigree (something that later leads to meddling officials trying to remove him from the King’s service), but he’s learned his skills as a speech therapist by helping shell-shocked World War I veterans – and he has the sensitivity to realize that the Duke’s problems are ultimately not physical, but emotional in nature, originating in the strictures placed on Albert early in his childhood by a cruel nurse and distant, uncomprehending parents. Thankfully, The King’s Speech is free of the usual cliched “training montage” that ends with a triumphal breakthrough for the protagonist. Rather, the Albert’s progress is shown to be slow and tortuous, requiring years of continual effort and few easy answers. This wouldn’t seem to matter so much, because Albert is after all the second son of the King, but his father King George V’s death in 1936 and his elder brother Edward’s sudden abdication as King in December of that year (in order to marry the American divorcee Wallis Simpson) suddenly thrusts Albert into the spotlight as the next monarch of Great Britain.

This is where The King’s Speech started to engage my interest in any serious manner. Truth be told, The King’s Speech is engaging and competent up to that point, but I’m used to well-made British period films – the British excel at them – and this one had somewhat dampened my enthusiasm early on by playing a number of scenes for easy laughs. As a potential Best Picture Oscar winner, I was hoping for more from the film than sit-com level jokes and a series of unnecessary scenes in which Albert is persuaded by Logue to swear with four letter words in order to “free himself” emotionally – scenes that historians have charged have no basis in fact and that are merely the latest example of our ’60s-inspired culture’s equation of the overthrow of civil norms with the acquisition of antinomian virtue.

However, as the clouds of war gather on the European continent and Albert prepares to become King George VI, the film draws into sharper focus the King’s need to speak clearly by contrasting it to the alarming rise of Hitler in Europe. This theme had been set up earlier in the film when the elder King George V lectured his son about the importance of speaking well over the new mass medium of radio because of the rise of Bolshevism in Russia and Fascism on the continent. As George V says to Albert: “Who’s going to stand between us, the jackboots, and the proletarian abyss?” If the King can’t articulate his role to the public, and serve the public by explaining to the world the need for their nation’s defense, he may soon find himself gone the way of his cousins the Russian czar and Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany – and worse yet, see his nation taken over by totalitarian tyranny.

There is one scene that communicates this idea especially well. Albert has just been crowned George VI in Westminster Abbey in May of 1937 and is watching the newsreels after the ceremony with his family. As the film switches to a newsreel of Hitler giving a speech in Germany, the projectionist moves to turn it off, but the king insists that it be kept on so he can watch it. He and the royal family watch in dismay as Hitler harangues a massive crowd in fluent, inflammatory rhetoric that is met with enthusiastic cheers. The newsreel ends, and the young Princess Elizabeth asks the king what Hitler was saying. The king replies: “I don’t know, but he seems to be saying it rather well.”

The implication is clear: Hitler, the evil tyrant who will soon plunge the world into war, is verbally adept and is able to use modern methods of mass communication – microphones to address huge rallies, radio and film reels to broadcast his words to the world – to persuade the German public to follow him down a nihilistic path of death and destruction. The only people who can challenge him will be the democratically-elected leaders of the world – and such symbolic figures as the royal families of Europe – who, although they hold no real power, must be able to speak persuasively to the public in order to remind them of their own humanistic traditions and inspire the public to defend freedom and life.

The King’s Speech dramatizes the need to take verbal adeptness seriously, to cultivate intelligent, well-spoken, principled leaders who can use modern means of communication to articulate crucial humanistic principles and fight back against the rise of totalitarianism and nihilism around the world. The end of the film states that thanks to his wartime speeches, George VI became to the British people “a symbol of national resistance.” In an era when American films feature heroes with supernatural powers who behave like kings and place themselves above the rest of humanity, how ironic that the Europeans – in this case the British – should make a film about a king who behaves like a human being and believes in liberty. Despite its occasional obvious moments, The King’s Speech is a fine, humanistic film that movingly supports the democratic principles that we here at Libertas hold dear.

[Editor’s Note: thus far The King’s Speech has won the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay (David Seidler).]

[UPDATE: Over the course of the evening, The King’s Speech won Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director (Tom Hooper), Best Actor (Colin Firth) and Best Original Screenplay (David Seidler)].

Posted on February 27th, 2011 at 6:37pm.