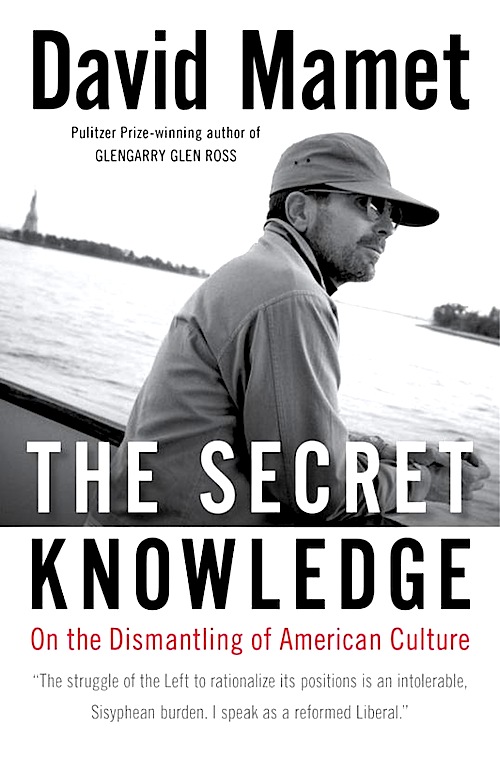

By David Ross. I wrote a while ago about David Mamet’s splashy conversion to conservatism (see here), about which I was naturally excited, Mamet being the highest ranking defector in the modern Cold War between right and left. I eagerly awaited his book, The Secret Knowledge: On the Dismantling of American Culture, hoping for a manifesto that would function as an elegant rapier thrust, or at least a solid groin kick, and hurt all the more coming from a man whom the left cannot write off as a cretin from the land of “low-sloping foreheads” (to borrow a phrase from New York Times columnist David Carr). Mamet has, after all, lent intellectual heft to Broadway and Hollywood for more than three decades.

By David Ross. I wrote a while ago about David Mamet’s splashy conversion to conservatism (see here), about which I was naturally excited, Mamet being the highest ranking defector in the modern Cold War between right and left. I eagerly awaited his book, The Secret Knowledge: On the Dismantling of American Culture, hoping for a manifesto that would function as an elegant rapier thrust, or at least a solid groin kick, and hurt all the more coming from a man whom the left cannot write off as a cretin from the land of “low-sloping foreheads” (to borrow a phrase from New York Times columnist David Carr). Mamet has, after all, lent intellectual heft to Broadway and Hollywood for more than three decades.

It pains me to confess that Mamet’s book is dreadful. It’s not, as one might imagine, that his conservatism turns out to be a smug centrism in the David Brooks mode or an idiosyncratic wire-drawn intellectual construct in the Hitchens mode. On the contrary, he shares the talk-radio mindset of bitter far-right disgust, and he seems sturdily committed to the entire Republican platform, for better and for worse. Conservatives will immediately recognize Mamet as their man.

The problem is twofold: 1) What seems to Mamet revelatory a year or two into his conservative phase is not so revelatory to those of us who’ve spent twenty or thirty years toiling in the conservative vineyards. He’s like a blind fellow who can suddenly see and proceeds to inform everybody that the sky is blue and the grass is green and chesty women look good in tight sweaters. 2) The book is badly argued (where it’s argued at all) and badly written in the basic mechanical sense. Mamet’s prose is gnarled and parenthetical and weirdly affectless (c.f. his nerveless, deadpan directorial style). It’s not as bad as Sean Penn’s prose, which is almost literary anti-matter (see here), but, lord, it ain’t good. Here’s a sample, cherry-picked only slightly:

If a country, a region, a race is in difficulty because of a lack of funds, any new or recurrent failure subsequent to any subvention in aid may be attributed to insufficient aid, and provide the rationale for that funding’s increase. But it may only do so given the acceptance of the nondemonstrable, indeed disprovable theory that government intervention increases wealth. (pg. 36)

This is to say, more or less, that governments like to throw good money after bad. I can only suppose that writing street-smart dramatic dialogue and writing elegant expository prose are entirely different skills, and that Mamet is a writer only in a restricted sense. Continue reading LFM Book Review: David Mamet’s The Secret Knowledge