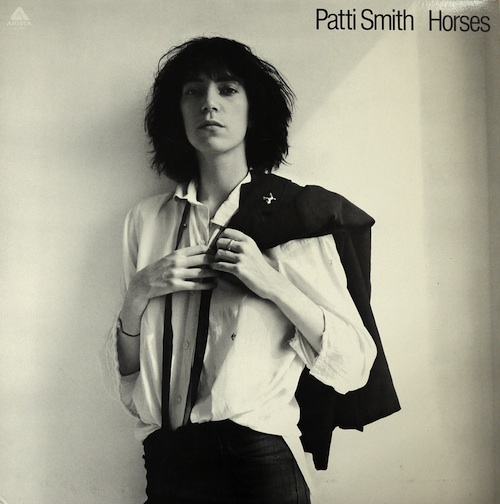

By David Ross. Let’s admit it. We all have a weak spot for certain women from the wrong side of the political tracks. Maybe you have little fantasies about discussing Bresson with Susan Sontag while soaping her back in the tub. Maybe you imagine sharing the Sunday paper with Joan Didion. My own weakness – lifelong – is for Patti Smith. I had a girlfriend who gamely stood in line to have Patti sign a CD copy of Horses for me. When she finally got to the front of the queue, she told Patti, “My boyfriend is in love with you.” Patti said, “Doesn’t he notice these grey hairs?” My girlfriend said, “I don’t think he cares.” Well spoken on my behalf.

William Blake offers – perhaps ‘records’ is the more appropriate verb – this exchange with the prophet Isaiah in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell:

Then I asked: “Does a firm persuasion that a thing is so, make it so?”

He replied, “All poets believe that it does, and in ages of imagination the firm persuasion removed mountains; but many are not capable of a firm persuasion of anything.” (V, 27-32).

What’s so alluring in the supra-physical sense is Patti’s capacity for this “firm persuasion.” She’s not mugging (like Bono) or merely howling (like Kurt Cobain): her music is a disciplined act of conviction in her own poetic and prophetic calling. One can look awfully silly as a self-styled poet or prophet (Jim Morrison certainly did) but Patti never waivers and never allows the spell to break; we’re convinced in the end because she’s utterly convinced from the start. Arguably, Patti was the last legitimate keeper of the romantic flame itself, that desperate belief in art that began in the late nineteenth century and guttered utterly in our own time.

A bony, boyish waif from Woodbury Gardens, NJ, Smith cut her teeth at the Chelsea Hotel and St. Mark’s Church during the late 1960s and early 1970s, achieving minor underground celebrity as an actress, playwright, rock journalist, artist, and poet. Her chief inspirations were predictable but nonetheless powerful: Rimbaud, Genet, Burroughs, Ginsberg, Dylan, Hendrix, the Rolling Stones. In 1971, she began to recite her poetry to guitarist Lenny Kaye’s accompaniment. By 1976, she had improbably become the most acclaimed female rock star since Janis Joplin and Grace Slick had emerged ten years earlier.

Smith’s first album, Horses (1975), weds cascades of Beat-and Symbolist-inflected poetry to the lean, driving sound of proto-punk garage rock. The album remains a signature argument for the artistry of rock’n’roll and is to my mind one of the ten supreme albums of the rock era. Rolling Stone ranks Horses 44th on its list of the 500 greatest albums of all time, just behind Dark Side of the Moon. This becomes a backhanded compliment when you consider certain albums that rank higher: the Eagles’ Hotel California (#37), Carol King’s Tapestry (#36), David Bowie’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (#35), U2’s The Joshua Tree (#26), Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours (#25), and Michael Jackson’s Thriller (#20). Preferring Tapestry to Horses is like preferring Jennifer Aniston to Veronica Lake – an aesthetic misjudgment that raises questions about one’s entire world view.

Smith’s first album, Horses (1975), weds cascades of Beat-and Symbolist-inflected poetry to the lean, driving sound of proto-punk garage rock. The album remains a signature argument for the artistry of rock’n’roll and is to my mind one of the ten supreme albums of the rock era. Rolling Stone ranks Horses 44th on its list of the 500 greatest albums of all time, just behind Dark Side of the Moon. This becomes a backhanded compliment when you consider certain albums that rank higher: the Eagles’ Hotel California (#37), Carol King’s Tapestry (#36), David Bowie’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (#35), U2’s The Joshua Tree (#26), Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours (#25), and Michael Jackson’s Thriller (#20). Preferring Tapestry to Horses is like preferring Jennifer Aniston to Veronica Lake – an aesthetic misjudgment that raises questions about one’s entire world view.

Judge for yourself: here is the epic studio version of “Birdland,” Smith’s fantastic synthesis of Arthur C. Clarke, Shelley’s Queen Mab, and the Book of Revelations. Ponder also these scruffy, raging, nearly epileptic live versions of “Horses” and “Gloria.” Continue reading Patti Smith

Even with his foibles and arguable failings totted up, DFW was the redeemer of his literary generation. He saved it from the humiliation of being the first generation in American history to lay nothing – not the least nosegay – on the graves of Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman. He saved it from the gaping wound of a great naught.

Even with his foibles and arguable failings totted up, DFW was the redeemer of his literary generation. He saved it from the humiliation of being the first generation in American history to lay nothing – not the least nosegay – on the graves of Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman. He saved it from the gaping wound of a great naught.