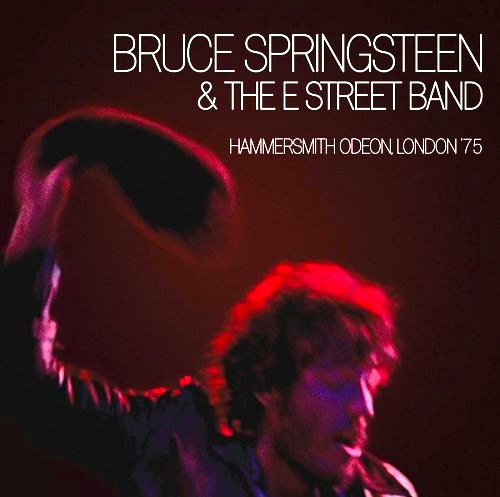

By David Ross. Rock has become such a ludicrous synergy of boobs without brains and b-schoolers without balls that it’s hard to remember why one ever cared. Springsteen’s Hammersmith Odeon London ’75, a sweating, writhing, heaving tent revival of an album, will remind one. When the album appeared in 2006, I knew instantly that my ears feasted on one of the supreme live albums: not a marginal addition to the giant Springsteen oeuvre, but a core masterpiece materialized out of nowhere to rival the likes of Coltrane’s Live at the Village Vanguard (1961), James Brown’s Live at the Apollo (1963), the Allman Brothers’ At Fillmore East (1971), and Bob Marley’s Live (1975). When I discovered that the concert had been released on DVD – that full footage existed – I felt as if the earth had split open and coughed up something like a 39th Shakespeare play or a 10th Beethoven symphony. Indeed, the DVD revealed what may be the greatest concert ever captured on film (a musical judgment; the film itself is pedestrian). I found myself entertaining the fantastic notion that the 1975 incarnation of the E Street Band is the greatest band ever – not remotely the best assemblage of individual musicians, but the best band, absolutely cohesive, committed, and co-equal, with a jazzy adventurism that it would eventually purge in favor of the irritating thump of Born in the U.S.A. The Odeon concert represents Springsteen at his very height, as much a deity of the American spirit as Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman.

By David Ross. Rock has become such a ludicrous synergy of boobs without brains and b-schoolers without balls that it’s hard to remember why one ever cared. Springsteen’s Hammersmith Odeon London ’75, a sweating, writhing, heaving tent revival of an album, will remind one. When the album appeared in 2006, I knew instantly that my ears feasted on one of the supreme live albums: not a marginal addition to the giant Springsteen oeuvre, but a core masterpiece materialized out of nowhere to rival the likes of Coltrane’s Live at the Village Vanguard (1961), James Brown’s Live at the Apollo (1963), the Allman Brothers’ At Fillmore East (1971), and Bob Marley’s Live (1975). When I discovered that the concert had been released on DVD – that full footage existed – I felt as if the earth had split open and coughed up something like a 39th Shakespeare play or a 10th Beethoven symphony. Indeed, the DVD revealed what may be the greatest concert ever captured on film (a musical judgment; the film itself is pedestrian). I found myself entertaining the fantastic notion that the 1975 incarnation of the E Street Band is the greatest band ever – not remotely the best assemblage of individual musicians, but the best band, absolutely cohesive, committed, and co-equal, with a jazzy adventurism that it would eventually purge in favor of the irritating thump of Born in the U.S.A. The Odeon concert represents Springsteen at his very height, as much a deity of the American spirit as Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman.

The record company, Rosie, gave me a big advance! This line, from “Rosalita,” of course, explodes not merely with the sense of release from tribulation but with the affirmation of the inevitability of release. It embodies what President Obama fails to understand when he says “I believe in American exceptionalism, just as the Greeks believe in Greek exceptionalism,” etc. There is such a thing as American exceptionalism: it is rooted in an amalgam of joy (sometimes tragic joy), energy, freedom, and providential faith. Socialism fails in American not least because everybody expects their own big advance to arrive at any moment, and the damnedest thing is that it does tend to arrive, not always in the form of a fat check from New York, but in the form of a realized dream: a kid in college, a small business that turns a corner and starts to pay the bills. Though he has lately become a celebrity leftist, Springsteen understands this entirely; indeed, he understands America far better than the president does. He understands as well, in a song like “Racing in the Streets,” which may be his most moving and profoundly perceiving, that while dreams do not always become glittering realities, our glory nonetheless is to have dreamt, and to have passed through the fading of the dream into a deeper reconciliation and grace.

The record company, Rosie, gave me a big advance! This line, from “Rosalita,” of course, explodes not merely with the sense of release from tribulation but with the affirmation of the inevitability of release. It embodies what President Obama fails to understand when he says “I believe in American exceptionalism, just as the Greeks believe in Greek exceptionalism,” etc. There is such a thing as American exceptionalism: it is rooted in an amalgam of joy (sometimes tragic joy), energy, freedom, and providential faith. Socialism fails in American not least because everybody expects their own big advance to arrive at any moment, and the damnedest thing is that it does tend to arrive, not always in the form of a fat check from New York, but in the form of a realized dream: a kid in college, a small business that turns a corner and starts to pay the bills. Though he has lately become a celebrity leftist, Springsteen understands this entirely; indeed, he understands America far better than the president does. He understands as well, in a song like “Racing in the Streets,” which may be his most moving and profoundly perceiving, that while dreams do not always become glittering realities, our glory nonetheless is to have dreamt, and to have passed through the fading of the dream into a deeper reconciliation and grace.

YouTube used to be awash in footage, but the abovementioned B-Schoolers have had it all purged. Sony might have let this one slip in the simple interest of disseminating something wonderful and assisting the efflorescence of the national spirit, but, of course, no. In any case, for the price of half an oil change you can buy the DVD.

Additional preferred rock and rock-related concert films, with dates of performance:

- Miriam Makeba, Live at Berns Salonger, Stockholm, Sweden, 1966

- The Complete Monterrey Pop Festival (1967)

- Jimi Hendrix, Live at Monterrey (1967)

- Stax/Volt Revue: Live in Norway 1967

- Elvis Presley, Elvis: ’68 Comeback Special (1968)

- Jimi Hendrix, Live at Woodstock (1969)

- The Rolling Stones, Gimme Shelter (1969)

- Woodstock: 3 Days of Peace & Music (1969) – deplorable generation, unmatched concert

- Joe Cocker, Mad Dogs and Englishmen (1970)

- The Beatles, Let it Be (1970)

- The Who, Isle of Wight Festival 1970 (1970)

- Led Zeppelin, Live at the Royal Albert Hall, 1970 (see the compilation titled Led Zeppelin)

- Neil Young, Live at Massey Hall (1971)

- The Band, The Last Waltz (1976)

- Patti Smith, Live in Stockholm (1976) – not exemplary, but I’ll take it.

- Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Sting, et al., The Secret Policeman’s Other Ball (1981)

- Stevie Ray Vaughan, Live at the El Mocambo (1983)

Sorry, but Stop Making Sense doesn’t interest me in the least; irony is to be transcended, not indulged. The raison d’etre of rock is conviction, with all its potential for foolishness and pretension.

On YouTube:

- Hendrix at Monterrey

- Joe Cocker, Mad Dogs lunacy

- The Last Waltz

- Patti Smith in Stockholm

- The Secret Policeman’s Other Ball

- Stevie Ray at the El Mocambo (here and here)

Posted on November 21st, 2010 at 12:06pm.