By David Ross. “Independent film” is defined by its circumvention of the Hollywood production mechanism, but this is incidental. The issue is not process but content. Independent film is an indigenous American genre just like the science-fiction film, the noir film, and the Western. Its chief attribute is loquacity. Talk is cheap – literally – and independent movies have made a virtue of necessity by rediscovering what Hollywood can afford to forget: that dialogue is the basis of drama. Less cardinal but still defining attributes include gritty naturalism (almost always urban), cultural and moral skepticism, a penchant for irony and deadpan, identification with pitiable outsiders and addled anti-heroes, impatience with traditional sequential narrative, appreciation for the retro, and a certain seated or merely ambulatory anti-kinesis (not a few films, like Slackers and Before Sunrise, narrate a literal walk). Independent film disdains the happy ending and could not care less about sex or sexiness or conventional good looks (hence Steve Buscemi). The operative politics tend to be amorphously anti-establishmentarian, but too skeptical to be actively liberal. I could make an excellent argument for the conservatism of films like Annie Hall (1997), Metropolitan (1990), Barcelona (1994), and A Serious Man (2009).

The films of the “Easy Rider, Raging Bull” era – films like John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (1969), Peter Bogdanovich’s Last Picture Show (1971), Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1973) and Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974), Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974), and Sydney Lumet’s Dog Day Afternoon – heralded the independent film movement, but were not strictly seminal. They yearned to be epic, mythic, and culturally central, with John Ford, Howard Hawks, and John Huston in mind. Independent cinema would later snort at these manly pretensions, settling for a peripheral and ironic self-awareness, like the satirical wallflower at the high school dance.

The films of the “Easy Rider, Raging Bull” era – films like John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (1969), Peter Bogdanovich’s Last Picture Show (1971), Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1973) and Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974), Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974), and Sydney Lumet’s Dog Day Afternoon – heralded the independent film movement, but were not strictly seminal. They yearned to be epic, mythic, and culturally central, with John Ford, Howard Hawks, and John Huston in mind. Independent cinema would later snort at these manly pretensions, settling for a peripheral and ironic self-awareness, like the satirical wallflower at the high school dance.

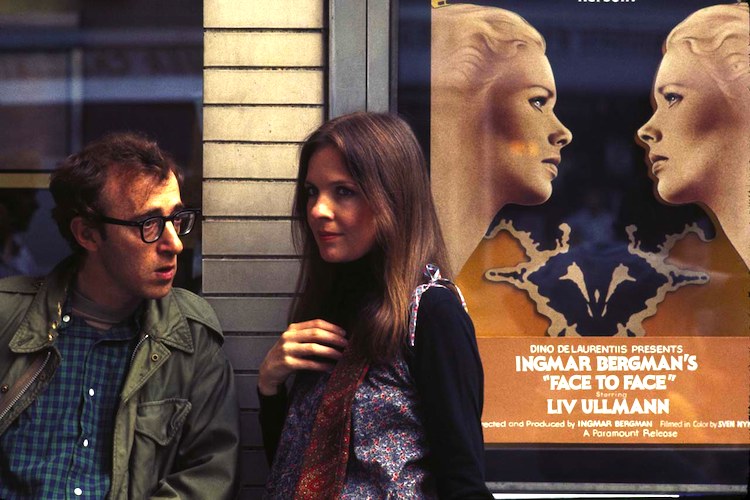

The first true – and possibly best – independent film was Annie Hall. Inspired by European conversationalists like Ingmar Bergman and Eric Rohmer, Woody Allen created an aggressively small and verbal film in an era of equally aggressive hypertrophy and hyperactivity. Perhaps even more to the point, Annie Hall was a quietly scathing critique of the post-sixties liberal and pop-cultural order, setting the tone for a whole generation of filmmakers united by the instinct that “something is wrong,” though skeptical of their own capacity for overt social statement in the style of seventies masterpieces like A Clockwork Orange (1971) and Network (1976). Gabby symposia like Louis Malle’s My Dinner with Andre (1981) and Barry Levinson’s Diner (1982) further crystallized the verbal and essentially seated nature of the genre.

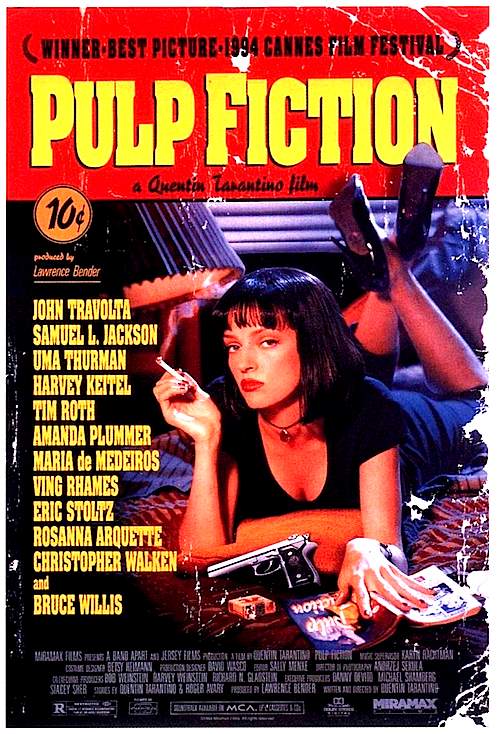

To my mind, the masterpieces of the genre are Annie Hall, Pulp Fiction (1994), The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), and nearly the entire slate of Coen brothers films, headed perhaps by Fargo (1996) and A Serious Man (2009). Independent films, however, are not really geared to be “masterpieces”; the “independent masterpiece” is almost an oxymoron. More characteristic are unassuming but insinuating films like Whit Stillman’s Metropolitan (1990), Buscemi’s Trees Lounge (1996), and Lisa Cholodenko’s High Art (1996). Trees Lounge is the 1927 Yankees of independent film; the cast includes Seymour Cassel, Lawrence Gilliard Jr. (later D’Angelo Barkdsale of The Wire), Michael Imperioli (later of The Sopranos), Samuel L. Jackson, Carol Kane, Debbie Mazar (later of Entourage), Chloe Sevigny, and of course Buscemi himself, the greatest independent actor of them all, the hangdog Humphrey Bogart of the genre. High Art‘s intersection of lesbianism, heroin, and photography is not for everybody, but few films are so well acted, tautly directed, and ruthlessly ironic; in a just world, Ally Sheedy and Patricia Clarkson would have shared an Oscar. The best independent comedies, films like Bruce Robinson’s Withnail and I (1987), David O. Russell’s Flirting with Disaster (1996), and Greg Mottola’s Superbad (2007), make utter mincemeat of Hollywood, whose well-paid, dull-witted writing committees have entirely lost the knack for producing laughs (“I know! Let’s pay Jim Carrey $20 million to make silly faces!”).

Without independent film, the television golden age of the Oughts would have been unthinkable. Curb Your Enthusiasm is the pure spawn of the independent film tradition, an almost perfect amalgamation of Annie Hall (nebbish Jewish guy on the cultural warpath) and Richard Linklater’s Slacker (serial encounters resulting in conversational chaos). The Simpsons, The Sopranos, Entourage, and Party Down are equally inconceivable.

Let me conclude by proposing a Hall of Fame of the independent film:

Annie Hall (1977, Woody Allen)

Manhattan (1979, Woody Allen)

Stardust Memories (1980, Woody Allen)

My Dinner with Andre (1981, Louis Malle)

Diner (1982, Barry Levinson)

Stranger than Paradise (1984, Jim Jarmush)

Broadway Danny Rose (1984, Woody Allen)

Blue Velvet (1986, David Lynch)

Hannah and Her Sisters (1986, Woody Allen)

Tin Men (1987, Barry Levinson)

Raising Arizona (1987, Coen brothers)

Barfly (1987, Barbet Schroeder)

Withnail and I (1987, Bruce Robinson)

Housekeeping (1987, Bill Forsyth)

The Navigator (1988, Vincent Ward)

Do the Right Thing (1989, Spike Lee)

Drugstore Cowboy (1989, Gus Van Sant)

Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989, Woody Allen)

Mystery Train (1989, Jim Jarmush)

Metropolitan (1990, Whit Stillman)

Barton Fink (1991, Joel Cohen)

Slacker (1991, Richard Linklater)

Reservoir Dogs (1992, Quentin Tarantino)

Night on Earth (1992, Jim Jarmush)

The Player (1992, Robert Altman)

Glengarry Glen Ross (1992, James Foley)

Husbands and Wives (1992, Woody Allen)

Dazed and Confused (1993, Richard Linklater)

Pulp Fiction (1994, Quentin Tarantino)

Short Cuts (1994, Robert Altman)

Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle (1994, Alan Parker)

Barcelona (1994, Whit Stillman)

Bullets over Broadway (1994, Woody Allen)

Crooklyn (1994, Spike Lee)

Clerks (1994, Kevin Smith)

Before Sunrise (1995, Richard Linklatter)

Spanking the Monkey (1995, David O. Russell)

Safe (1995, Todd Haynes)

Kids (1995, Larry Clark)

Thirteen (1995, Catherine Hardwicke)

Fargo (1996, Coen Brothers)

Flirting with Disaster (1996, David O. Russell)

Trees Lounge (1996, Steve Buscemi)

Big Night (1996, Campbell Scott, Stanley Tucci)

Jackie Brown (1997, Quentin Tarantino)

Good Will Hunting (1997, Gus Van Zant)

A Simple Plan (1998, Sam Raimi)

Rushmore (1998, Wes Anderson)

High Art (1998, Lisa Cholodenko)

Lock, Stock, and Two Smoking Barrels (1998, Guy Ritchie)

American Movie (1999, Chris Smith)

The Blair Witch Project (1999, Daniel Myrick, Eduardo Sánchez)

Snatch (2000, Guy Ritchie)

Royal Tenenbaums (2001, Wes Anderson)

Mulholland Drive (2001, David Lynch)

Tape (2001, Richard Linklater)

The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001, Coen Brothers)

Ghost World (2001, Terry Zwigoff)

Dogtown and Z-Boys (2002, Tracy Peralta)

Waking Life (2003, Richard Linklater)

Igby Goes Down (2003, Burr Steers)

Intolerable Cruelty (2003, Coen Brothers)

Kill Bill (Tarantino, 2003-2004)

Sideways (Alexander Payne, 2004)

The Ladykillers (2004, Coen Brothers)

Borat (2006, Sacha Baron Cohen)

Art School Confidential (2006, Terry Zwigoff)

No Country for Old Men (2007, Coen Brothers)

Superbad (2007, Greg Mottola)

Deathproof (2007, Quentin Tarantino)

Burn After Reading (2008, Coen Brothers)

Adventureland (2008, Greg Mottola)

A Serious Man (2009, Coen Brothers)

For additional comments on Whit Stillman see here; for related comments on the “Golden Age of the Nerd” see here and here.

Posted on August 18th, 2011 at 9:13am.

First, that’s a great piece, and one that’s a long time coming.

Let me just say, Mr. Ross, that I do not believe you share these beliefs, but I found “A Serious Man” to be the most condescending, anti-Semitic film made in years. I know the Coen brothers (who I LOVE!) made the film, but it just had a nasty little stereotypical, self-hating feel to it that killed the experience for me.

From your too many film on that list to even name a few, but Fargo, No Country For Old Men, Adventureland, Raising Arizona, Kill Bill, and Dazed and Confused jump out at me.

A couple films I would add — if they would even qualify — are The Usual Suspects and Redbelt. David Mamet’s take on a martial arts picture, and his examination of MMA and Hollywood machinations completely hypnotized me.

I like Clerks well enough, but I HATE its effects. Now, it’s trendy to look at Star Wars from the whole “what about the contractors on the Death Star” angle. Star Wars is mythology — told in a metaphorical language — where things like the Death Star are symbols. Sorry, that just bugs me.

Vince,

I am myself Jewish — a Minnesota Jew no less — as are the Coen brothers. Is A Serious Man anti-Semitic? I don’t think so. On the contrary, I think it’s one of the only films ever made in the spirit of the Old — rather than New — Testament, and one of the more earnest (if also comic) theological meditations in the history of the film. I recommend you have a look at Ruth Wisse’s article “A Serious Film” in the Dec. 2009 issue of Commentary. Wisse is a politically conservative professor of Hebrew at Harvard. The film passes muster with her no less than with me.

I appreciate that response, David. Perhaps it was the mood I was in when I saw it, but I’m open to giving the film another shot … the Coens have earned that type of respect from me.

David- I think two of the important aesthetic predecessors to the independent film style would be the Italian Neorealist and French New Wave movements. Both in their own way were ‘independent’ film movements that originated outside of the mainstream of Italian and French establishment filmmaking. Both were characterized by low budgets, gritty realism, an emphasis on dialogue and character over action, and that ironic or fatalistic attitude toward political and social norms that you refer to in your piece. Therefore I would add Neorealist films like Visconti’s “Ossessione” and Fellini’s “Nights of Cabiria” as well as New Wave films like Godard’s “Breathless” and ‘La Chinoise” to my own list of seminal independent films.

Finally, I assume you’re familiar with Peter Biskind’s “Easy Riders Raging Bulls” (one of the best accounts of the ’60s-’70s generation of New Hollywood filmmakers), but have you read his “Down and Dirty Pictures”? It’s an excellent account of the rise of Sundance and Miramax in the ’80s and ’90s and their roles as the twin engines of the modern independent film movement.

David – I’ll also add – any list of classic independent films would have to include something by John Cassavetes, the ultimate independent director in the ’60s and ’70s. My pick would be his gritty chamber drama “Faces” (1968) starring Gena Rowlands and Seymour Cassel. Unlike many on this list who received some degree of studio funding (such as Allen), Cassavetes entirely self-financed his films and can truly be considered the father of modern American independent film.

Great piece and comments as well. Nice to see the Libertas imprimatur given to Peter Biskind’s two books, both of which I thought were outstanding. (Conversely, I found his Warren Beatty bio to be mediocre, perhaps due to his closeness to the subject.)

Phil – thanks for the nice comment. We’re big fans of Peter Biskind here. I’ve given a number of indie film friends copies of “Easy Riders Raging Bulls” just because I found the book so inspiring. It was fascinating for me as an independent filmmaker to read about how that ’60s-’70s generation was able to have such an influence on Hollywood by making idiosyncratic and personal films.

You’re right, it is fascinating to see how that sensibility had the impact on Hollywood that it did. I have a minor quibble with the timeline reflected by films included in the article. I might have pushed the beginning of the Independent Hall of Fame back a little more to include Easy Rider and some Cassavetes films.

This is a good list that gets to the heart of the American Indie style that arose in the eighties and nineties. Given those parameters, the only thing I see missing is Whit Stillman’s Last Days of Disco and something by Noah Baumbach, probably Kicking and Screaming. Oh, and Catherine Hardwicke’s Thirteen is from 2003, not 1995. (And that is a film I would not let anywhere near my list–totally over-the-top and exaggerated.)

Also, perhaps this is out of the bounds of your category, but no Charlie Kaufman movies? Maybe I’m confused and none of them qualify as independent films, but they seem to fit the criteria otherwise.

I would note, though, that while this reflects “indie films” as a genre which is characterized by snappy dialogue, quirky characters, and retro style, there are quite a few independent films coming out now that don’t fit into this style/genre. In particular, I think some of the strongest work out there is coming from directors focusing on a new regionalism, minimalism, and poeticism that emphasizes naturalistic characters over sharply written dialogue. Films that fit into this group, IMO, would be David Gordon Green’s “George Washington,” “All the Real Girls,” and “Undertow,” Kelly Reichardt’s “Old Joy,” “Wendy and Lucy,” and “Meek’s Cutoff,” Jeff Nichols’ “Shotgun Stories” (and probably “Take Shelter”), Debra Granik’s “Winter’s Bone,” Phil Morrison’s “Junebug,” Jeff Rohal’s “The Guatemalan Handshake,” and quite a few more. I think this is sort of an emerging style of its own, and I’d like to see it go further. There is a wonderful focus on the little backwaters of America that can shift from taut crime narratives to gorgeous evocations of folklore in these movies that I think is really valuable.