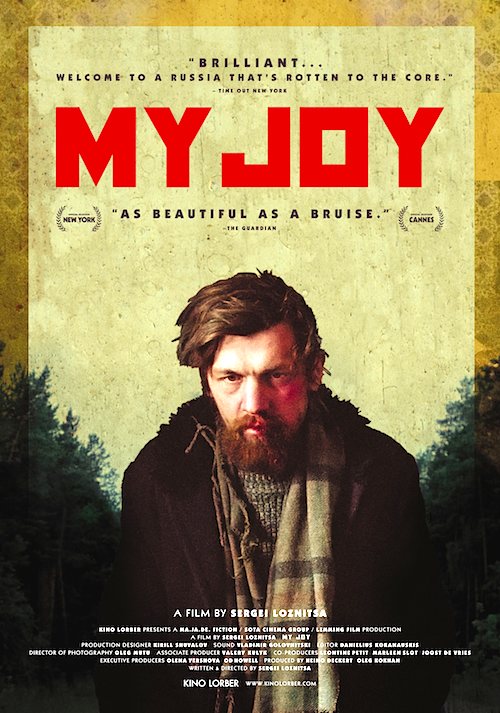

By Joe Bendel. Like any place, Russia has its share of urban legends, but Russia’s seem to carry the oppressive weight of the country’s tragic history. At least, such seems to be the case with the stories that inspired documentarian Sergei Loznitsa’s narrative feature debut, My Joy (trailer here), which opened yesterday in New York.

By Joe Bendel. Like any place, Russia has its share of urban legends, but Russia’s seem to carry the oppressive weight of the country’s tragic history. At least, such seems to be the case with the stories that inspired documentarian Sergei Loznitsa’s narrative feature debut, My Joy (trailer here), which opened yesterday in New York.

Having spent considerable time on the road, truck driver Georgy is no babe in the woods. He is hardly shocked by the venal cops who hassle him or the teenaged (if that) prostitute hustling business when a major accident closes the highway. Still, he tries to help her, but like contemporary Russia, she will have none of it. However, his trip goes seriously awry when he tries to take a detour around the backed-up traffic.

Though not overtly supernatural, the fateful back road takes the driver into a very malevolent place, somewhat in the spirit of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Like a horror film written by Beckett, Georgy is sucked into an absurdist village, where predatory behavior is the norm. Time becomes indeterminate in this twilight world, with the tragic past echoing strongly in the corrupt present day.

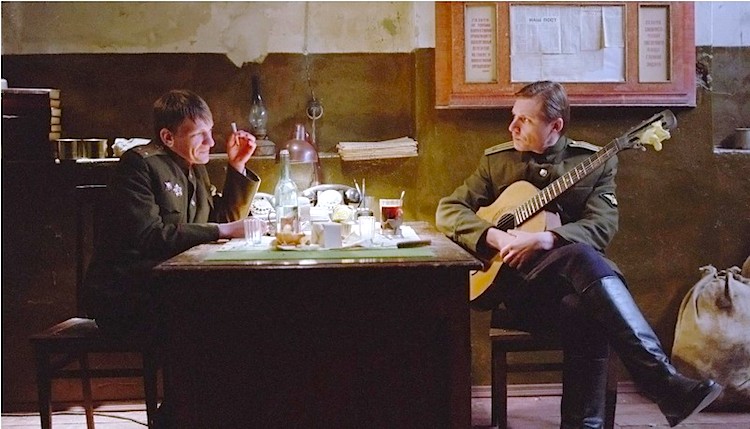

This is particularly true of an old hitchhiker’s story, easily the film’s strongest mini-arc. According to the mysterious stranger, he had been a heroic Lieutenant during WWII, but when a crooked local Commander robbed and humiliated him, his response permanently relegated the man to the nameless margins of Russian society. One of many discursive interludes, the Lieutenant’s flashback is rather bold because it directly challenges the great patriotic mythos built around the Soviet war years, as do the mutterings of a quite possibly mad veteran, apparently boasting of a Katyn Forest style massacre, heard later in the film.

Loznitsa presents a vision of a country sick in psyche, where those who have served it best are victimized the worst. He does not exactly tell this story in a straight line, bouncing off characters and subplots like a pinball. Frankly, Joy can be a little tricky to follow, but the heavy parts are hard to miss.

Though a Russian narrative, Joy was filmed in Ukraine working with a Romanian cinematographer, Oleg Mutu, who lensed acclaimed films like Tales From the Golden Age and 4 Months 3 Weeks and 2 Days. He vividly conveys a sense of the harshness of a Russian winter and the dreariness of Georgy’s village with no exit.

As befits the material, Loznitsa’s cast is appropriately dour and weathered looking. If not exactly charismatic, Viktor Nemets is rather scarily effective as the protagonist, losing all sense of persona in the madness enveloping him. Again, perhaps the strongest turn comes from Alexey Vertkov, who is viscerally intense as the Lieutenant whose story might be “fake but true” as the old media likes to say.

With its sometimes murky connections and several subplots that sputter out as soon as they are introduced, Joy is undeniably messy. Yet things tie together in intriguing ways, perhaps requiring repeated viewing to fully pick up on. It also holds an unflattering mirror up to Mother Russia, both present and past. Indeed, when it works, it is viscerally powerful stuff. Recommended for those well versed in the thematically and stylistically similar films of the Romanian New Wave, Joy opened yesterday in New York at the Cinema Village.

Posted on October 1st, 2011 at 11:37am.