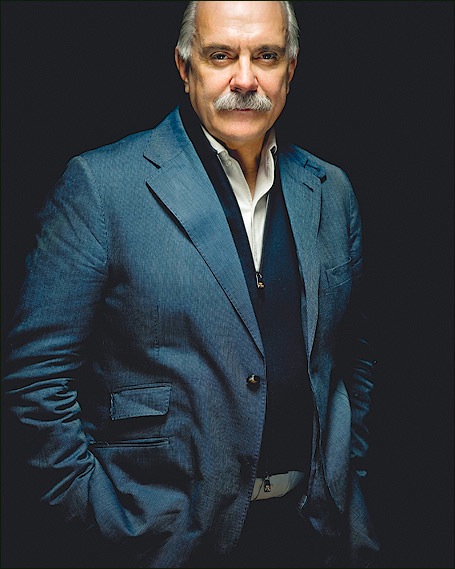

By Govindini Murty. Variety announced on June 22nd that Nikita Mikhalkov, one of Russia’s leading filmmakers, will be honored with a Crystal Globe for “Outstanding Artistic Contribution to World Cinema” at the upcoming Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in Czechoslovakia (taking place July 2-10, 2010). This news item caught my attention because Mikhalkov, the Academy Award-winning director of Burnt By the Sun, has been getting a lot of attention in Europe lately for his strongly Russian nationalist and Slavophilic views. Mikhalkov’s recent film Burnt By the Sun 2: Exodus aroused controversy in Europe this past spring because it was partially financed by the Russian government and received an extensive marketing campaign from them (including a red-carpet premiere with thousands of guests at the Kremlin), and allegedly contains pro-Russian nationalist propaganda. Burnt By the Sun 2 is the most expensive Russian film ever made with a budget of $55 million dollars, and yet it flopped at the Russian box office, making only $2.5 million dollars its opening weekend – in large part due to public controversy over Mikhalkov’s close ties to Vladimir Putin and the current Russian regime.

Nonetheless, the Cannes Film Festival screened Burnt by the Sun 2 this past May, and now the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival is giving Mikhalkov its foremost award for his body of work. Nikita Mikhalkov is undeniably a talented actor, director, and producer with an accomplished cinematic oevre. However, given Mikhalkov’s controversial political statements (such as his open letter in 2007 asking Putin not to step down after his term of office expired), and the strongly Russian nationalist content of his recent films, it’s interesting that Karlovy Vary – one of Europe’s premiere film festivals – would be honoring him this year. There has been little discussion in America of Burnt By the Sun 2 or of other Mikhalkov films like 1612 and The Barber of Siberia (in part because they have not been released here), but they are important nonetheless as evidence of a resurgent nationalism in the Russian cinema that may have political repercussions for America and the rest of the world.

Nikita Mikhalkov comes from a noted Russian artistic family. His father wrote the lyrics to both the Soviet and Russian national anthems, his mother was a poetess, and his brother Andrei Konchalovsky is an acclaimed director of such films as Siberiade and The Inner Circle. Mikhalkov has acted in and directed films since the 1960s, with his breakthrough film coming in 1974 with At Home Among Strangers (an ostern, or “eastern” that was the Soviet answer to the popular American westerns). Mikhalkov’s biggest success, though, has been Burnt By the Sun (1994), which won both the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film and the Grand Prize at Cannes. Burnt By the Sun tells the story of a loyal Soviet colonel in the 1930s who was falsely accused of treachery by Stalin and condemned to death. The film received acclaim in the West for being one of the few films made in post-Soviet Russia to criticize the horrors of communism.

Mikhalkov followed this courageous defense of democratic freedom, though, by turning toward Russian nationalism. His 1998 film The Barber of Siberia was a patriotic historical epic in which Mikhalkov himself played Tsar Alexander III. Some saw this as preparation for a run by Mikhalkov for political office. His Wikipedia biography notes: “The film received the Russia State Prize and spawned rumours about Mikhalkov’s presidential ambitions.”

In 2007 Mikhalkov produced 1612, a patriotic historical epic commissioned by the Kremlin and partially funded by oligarch Viktor Vekselberg (best known in the West for buying up Russian imperial Faberge eggs so they could be repatriated to Russia). Directed by Vladimir Khotinenko, the film was intended to commemorate the victory in 1612 of Russian forces over Polish-Lithuanian invaders who’d wrought havoc in Russia during a period known as “The Time of Troubles” (that took place in the interregnum between the end of the Rurik dynasty in 1598 and the beginning of the Romanov dynasty in 1613 under Tsar Michael Romanov). The Kremlin commissioned the historical film in order to mark the creation of a new national holiday on November 4th. (And in the best Russian imperial style, 1612 was celebrated in Moscow with a lavish red-carpet premiere – complete with Russian models in white leather handing out birch-flavored vodka to guests.) However, many saw the film as an obvious allegory of modern Russia’s own “Time of Troubles” in the 1990s after the fall of Communism, which was ended by the tsar-like rise of Vladimir Putin in 2000. As Chris Baldwin reports in this Reuters article:

In a film that hit cinema screens this week, patriotic Russians despairing at the lack of a strong leader rise up, throw out their Western overlords and make Russia a proud country once again. It could be a documentary about how President Vladimir Putin put an end to the turmoil that followed the Soviet Union’s collapse. In fact, it is based on a period in the 17th century known as the “Time of Troubles”. But the parallels may be more than a coincidence: the film was commissioned by the Kremlin to mark National Unity Day on Sunday, and the director makes little secret that it is an allegory for modern Russia. The film is being released a month before Russia votes in a parliamentary election that many observers say is a referendum on Putin’s rule, during which he has accumulated huge power and hit back at what he calls Western encroachment. “I … consider the 17th century an extremely important period in our history, without which you simply cannot understand Russia,” director Vladimir Khotinenko said in an interview with the Izvestia newspaper. “And now those times are really relevant,” he said. “I am talking about the period after Perestroika. We lived in a Time of Troubles. Its duration even coincided with the one in the 17th century.” He added: “I’m convinced — and I have nothing against democracy — that Russians have a strong desire for a Tsar.”

The Herald Scotland is scathing in its assessment of the film, comparing it to “Soviet-era propaganda”:

[The film] showcases key ideas being pushed by the Kremlin at a time when it faces parliamentary and presidential elections: the necessity of strong leadership; treacherous foreigners; and the importance of patriotism. … During the so-called “time of troubles” in the early 17th century, Moscow slipped into lawlessness, foreign armies vied for control, famine stalked the land, and the tsardom lacked any leadership. The chaos in Moscow ended after an uprising drove the foreign invaders out, setting the stage for the Romanov dynasty to rule Russia for the next 300 years. Mikhail Romanov was crowned Tsar in 1613, heralding the arrival of a period of Russian expansion. Putin’s aides are keen to promote the idea that the events of 1612 have been replayed almost 400 years later. Post-Soviet Russia’s “time of troubles” was, they say, the anarchic 1990s when Boris Yeltsin presided over a weak, criminalised state heavily influenced by Washington. And of course it is Putin, they say, who is the country’s latter-day Tsar who has restored order and banished treacherous foreign influence. “It’s important for me that the audience feel pride,” said director Vladimir Khotinenko. “That they didn’t regard it as something that happened in ancient history but as a recent event. That they felt the link between what happened 400 years ago and today.” … [But as one detractor says:] “With the help of culture you can create simplified versions of reality that are hugely beneficial to government,” [writes] historian Igor Dolutskii.

And that’s the problem, isn’t it? Political propaganda inevitably plays havoc with the truth, and that is why it’s often so opposed to the aim of art, which is to serve the truth. Art inevitably represents the complexities of reality in ways that are opposed to propaganda, which must simplify reality in order to promote a party line.

Now Mikhalkov has written, directed, produced, and played the lead in Burnt By the Sun 2, released in Russia in April of 2010. The film resurrects Mikhalkov’s character, the Soviet general Sergei Kotov, and has him now fighting the Nazis in World War II. The film is intended by Mikhalkov to be a paean to the heroism of Russian soldiers who fought the Germans on the eastern front (a modern day Alexander Nevsky, if you will). Critics are charging, though, that the film contains not only Russian nationalist propaganda, but also Orthodox Christian propaganda. As the UK Guardian reports:

… Mikhalkov’s character, Sergei Kotov, escapes after German bombers blow up his gulag. He is soon defending the motherland from fascist tanks. Russia’s critics, however, have reacted badly to the blockbuster, dismissing it as “portentous and untruthful”. Writing on his blog, cinema critic Yuri Gladilshikov noted war veterans had said it did not resemble their experience of fighting at the front. “There are a heap of reasons to dislike it,” Gladilshikov wrote, citing the film’s brutal battlefield naturalism, its promotion of orthodox Christianity, and a gratuitous topless scene involving Mikhalkov’s daughter Nadia, who repeats her previous acting job as Kotov’s daughter. The critics have also taken a swipe at a clumsy state-backed PR campaign to promote the film. It has been deliberately released ahead of May 9, when Russia celebrates the 65th anniversary of its victory over Nazi Germany. The premiere took place inside the Kremlin. Russia’s prime minister, Vladimir Putin, did not manage to turn up. But Mikhalkov’s fervent support for Putin and his strong Russian nationalist views are well known. The film has many virtuoso setpieces but sticks closely to the Kremlin’s approved version of the war: as the heroic Soviet triumph over Nazi barbarity. This fact appears to have put the public off: the film has played to near empty halls, with box office receipts of just $2.5m from its opening weekend. Burnt by the Sun 2 cost a record $55m to make. “The reasons it has flopped are psychological [not artistic],” critic Oleg Zolotarev said. “Mikhalkov is no longer seen as a director but as a state bureaucrat.”

However, Kirk Honeycutt of the Hollywood Reporter says that Burnt By the Sun 2 is actually much better than critics have charged, and that the film has fallen victim to the changing political mood in Russia. Honeycutt says in his review of the film:

“Burnt by the Sun 2” [is] a much, much better film than its Russian reviews would indicate. The film hews closer in tone to Joseph Heller’s darkly comic war novel “Catch-22” than most war movies. Sequences of utter absurdity abound while characters suffering comically from shell shock wander in a devastated landscape of much cruelty. Brutal battles — and who lives or dies — pivot on total caprice. … The film does get off to an awkward start with a fantasy sequence in which a pasty-faced actor plays Stalin, who winds up with his face in a birthday cake. But when General Kotov, played once again by Mikhalkov, awakens in a prison camp, the film finds its footing in turns of events that contain such bitter irony.

It’s all the more interesting therefore that the Russian public would reject the film; I think it’s a rejection not so much of patriotism or of the subject matter of World War II, but of Putin and those who are seen to be too close to his regime. Not only did Mikhalkov produce a special TV program for Putin’s 55th birthday and write an open letter in 2007 asking Putin not to step down from office when his term expired (Mikhalkov’s letter to Putin said: “Russia needs your talents and wisdom”), but Mikhalkov also consistently gets the most funding of any Russian director/producer and runs most of Russia’s major film organizations.

In a controversial election full of charges of vote-rigging, Mikhalkov was elected chairman of the Russian Cinematographers’ Union, the largest filmmaking organization in Russia; Mikhalkov is also president of the Moscow International Film Festival, the Russian Culture Fund, and the National Academy which gives out the Golden Eagle Award – one of Russia’s major awards. It’s amazing that once again in Russia – whether in politics or in film – there is this move to concentrate all power in one man’s hands. Whatever Mikhalkov’s virtues may be – perhaps he’s been unjustly smeared by his rivals – the fact remains that he has an unprecedented level of power in the Russian film industry. And there has been a reaction: after Mikhalkov was criticized for his “vertical” and “autocratic” style of management of the Cinematographers’ Union, a number of filmmakers broke away to start their own union in April of 2010.

Nonetheless, Nikita Mikhalkov still has a lot of support in Russia, and he is even now in the midst of producing Burnt by the Sun 3. Mikhalkov’s strongly pro-Russian, nationalist and pro-Orthodox Christian views may be scandalous to some, but the honors that are being given to him this year by major film festivals like Cannes and Karlovy Vary show that the Europeans recognize that he is still a force to be reckoned with. As such, it is interesting to take a further look at Mikhalkov’s political statements and what they may portend for the future of the Russian film industry. According to Mikhalkov’s biography on Wikipedia:

In 2008 he visited Serbia to support Tomislav Nikolić who was running as the ultra-nationalist candidate for the Serb presidency at the time. Mikhalkov took part in a meeting of “Nomocanon,” a Serb youth organization which denies war crimes committed by Serbs in the 1992-99 Yugoslav wars. In a speech given to the organization, Mikhalkov spoke about a “war against Orthodoxy” wherein he cited Orthodox Christianity as “the main force which opposes cultural and intellectual McDonald’s.” In response to his statement, a journalist asked Mikhalkov: “Which is better, McDonald’s or Stalinism?” Mikhalkov answered: “That depends on the person.”

We’ve been covering this past week on LFM a variety of films from eastern Europe and Russia that shed a fascinating light on that part of the world’s fraught relationship between its artists and its statist regimes. Jennifer Baldwin’s overview of the Czech New Wave highlights the subversive creativity of that cinematic movement in the face of Communist repression. Jason Apuzzo’s review of the Estonian/Finnish film Disco and Atomic War tells the eye-opening story of how Finnish broadcasts of American movies and TV shows like Star Wars, Knight Rider, and Dallas into Soviet Estonia may have helped bring down the Communist regime. Joe Bendel’s review of the documentary Vlast (“Power”) about Vladimir Putin’s persecution of Moscow businessman and democracy-advocate Mikhail Khodorkovsky provides a shocking view into how far the current Russian regime will go to punish its critics. Now at LFM we discuss the interesting anomaly of Nikita Mikhalkov, a multitalented filmmaker who has spoken out against Communism and whose films have often defended love, individual conscience, and human values – yet who now is allied with an authoritarian Russian regime that appears to be repressing those very values by resurrecting elements of both the Communist and Tsarist states. This is a contradiction if I have ever heard of one.

Nikita Mikhalkov is at the center of what appears to be a new nationalist movement in the Russian cinema that sheds a fascinating light on contemporary Russian culture and politics – but whether this movement genuinely reflects the mood of the Russian people, or is just an imposition of its leaders, remains to be seen.

Posted by June 23rd, 2010 at 5:28pm.

I loved “The Fall of Berlin”, the Soviet era movie detailing the Great Patriotic War and the hero workers who fought it. I’ll be looking for “Burnt by the Sun 2” on DVD.

I haven’t seen “The Fall of Berlin.” I’ll have to look for it.

Is it just me, or is this a really alarming development? What happened in Georgia could happen elsewhere. Putin doesn’t need any more encouragement than he’s already getting.

A very well-written, well-researched and interesting post Govindini. In many ways it highlights the dilemma faced by an artist who needs financing for film projects. Even where there is a well-established film industry, as in Hollywood, there can often be a political aspect to what gets financed. Where government financing is involved, it can create a great deal of suspicion among those who are not fully happy with the government they have about the motives of a film-maker who accepts funding from that government… Comparisions also arise in the example of the Oliver Stone movie about Chavez…it has also been a commercial failure. Not so much because it was financed by the Venezuala government, but because the president is so unpopular in his own country. I suppose the answer to the dilemma is to hope that things will balance out…that financing becomes available for a variety of points of view, the left, the right, pro-government and anti-government, with the film maker having the freedom to not only express himself but also having access to funding that does not compromise his principles and beliefs. This could lead to the production of films exhibiting a wide range of principles and beliefs just as these are exhibited in a typical cross-section of society. Regrettably production of films exhibiting such a wide range is not happening in either America or Russia in the present day. It all seems terribly out of balance and something needs to be done to get film-making back in balance in such a way that a variety of viewpoints is reflected in modern-day film. Nothing new to be saying on Libertas…seems to be something that you and Jason have been talking about for some time. Can’t talk about it enough – maybe someday someone will do something about it!

Thanks so much for your comment Looksoverpark. I do indeed look forward to the day when there will be financing for films with a greater variety of viewpoints! As for government financing, yes, it is a sort of Faustian bargain. On the one hand, most of the government financing in the US, Canada, and European countries goes to predominantly left-wing filmmakers who are able to find subjects that will please government bureaucrats. Obviously I have concerns about that. On the other hand, in some countries – such as Canada or even France and Germany – if there was no government financing the filmmaking output of these nations would plummet and they would have almost no national film industries. It’s a complex situation. The problem for conservatives is, not only do they not get government financing (even if I approved of such a thing), they get next to no financing from the private sector either because conservative businesspeople are not willing to support conservative artists. It’s really an appalling situation, and not very good for the cultural diversity of America.

That’s all on point, but I just see it as the most recent in over-the-top Russian blindness. That’s far less threatening to me not because it’s right-wing, but because it matters little politically (compare him to lefties in world cinema). Also, the movie’s failure is that it’s genuinely terrible. Not that-one-Chinese-history-of-Communism-stilted-mess bad, but awful. I’m also not sure it’s of a piece. Tarkovskii’s still far more influential than Mikhalkov, and he’s been dead for years.

I would hardly say that Mikhalkov is right wing in the American sense. He’s openly stated he’s a monarchist, while the American right-wing is very much democratic and believes in the Founding Fathers and the American Revolution.

As for Mikhalkov not having the cinematic influence of Tarkovsky – that was not my point either (and we’re big fans of Tarkovsky here). The point is that a tremendous amount of power over Russian filmmaking is in the hands of one person – Mikhalkov – who is also close to the Kremlin and gets most of the financing in Russia. It reveals the state of mind and the centralizing instincts of the Russian establishment – and this is definitely relevant for all of us.

Why are all these major film festivals honoring Mikhalkov now, when, as you say, he’s had not much cinematic influence? Not only did he get a special award from the Venice Film Festival a few years ago, this year Cannes showed “Burnt By the Sun 2” and allowed it to compete for awards (even though it had premiered elsewhere), and Karlovy Vary is giving him a big tribute and also screening the film. What I’m pointing out is that these honors may be the Europeans trying to appease Putin and his allies. Since LFM is a film site that is interested in international cinema, this reveals provocative things about the mindset of the European film industry.

People need to be aware of the Russian nationalist threat and should pay more attention to its cinema as evidence of that. I believe that is this article’s point.