[EDITOR’S NOTE: The New York Post’s Kyle Smith suddenly has a column out today (8/17) entitled “The Clockwork riots,” which compares the London riots to both the Burgess and Kubrick versions of A Clockwork Orange, referring to the “prophetic” nature of those works, as well as to the ongoing crime “orgy” in London. No attribution is made to Libertas. This seems to be a striking coincidence. We would appreciate a clarification from Mr. Smith.]

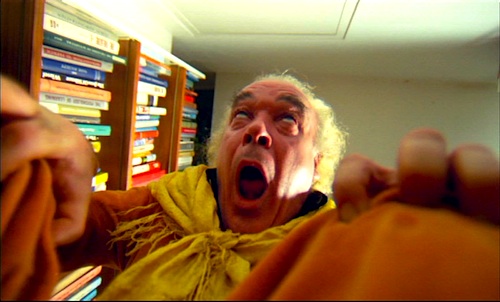

By David Ross. A Clockwork Orange, Kubrick’s classic interpretation of Anthony Burgess’ 1962 novel, is no longer prophetic. It is actual. The realization of its vision is unmistakable as London mobs of juvenile miscreants burn and loot, differing from Malcolm McDowell’s Alex DeLarge only insofar as they would not be caught dead listening to Beethoven. We are witnessing the nanny state eventuate in its logical terminus: abdication of personal responsibility, dissolution of purpose, collapse of belief, crippling unconscious sense of one’s own infantilization. As Mark Steyn says, “Big government means small citizens.”

This seems to me the movie’s crucial exchange:

Tramp: Well, go on, do me in you bastard cowards! I don’t want to live anyway, not in a stinking world like this!

Alex: Oh? And what’s so stinking about it?

Tramp: It’s a stinking world because there’s no law and order anymore! It’s a stinking world because it lets the young get on to the old, like you done. Oh, it’s no world for an old man any longer. What sort of a world is it at all? Men on the moon, and men spinning around the earth, and there’s not no attention paid to earthly law and order no more.

“No attention paid to Earthly law and order” is a curious and pregnant phrase. The tramp wants to complain not merely about crime, but about alienation from something more fundamental than the penal code. The exasperated allusion to “men on the moon” implicates that rationalism and materialism of a post-religious age. Seduced by our new powers of knowledge and control, we’ve lost sight of basic truths and duties.

Just now I’m reading Elizabeth Gaskell’s 1857 biography of Charlotte Bronte. As the yobs spread their mayhem, I can’t help thinking of the three Bronte sisters, their mother dead, their two elder sisters dead, no schooling to speak of, no money to speak of, nothing but the cold and howling Yorkshire wind for company, and yet toiling to master French, German, politics, history, and literature, and eventually promulgating, from the nursery of a provincial parsonage, one of the great literary sprees in all history. How is it that their kind has become so utterly inconceivable?

I ponder also the elderly shop-owner who sold the Bronte sisters their paper. He writes to Gaskell,

They used to buy a great deal of writing paper, and I used to wonder whatever they did with so much. I sometimes thought they contributed to the Magazines. When I was out of stock, I was always afraid of their coming; they seemed so distressed about it, if I had none. I have walked to Halifax (a distance of 10 miles) many a time, for half a ream of paper, for fear of being without it when they came. [ ] Though I am a poor working man (which I have never felt to be any degradation), I could talk with [Charlotte Bronte] with the greatest freedom. I always felt quite at home with her. Though I never had any school education, I never felt the want of it in her company.

Thus two Englands almost inconceivable in their historical relation. On the one hand, we have mobs of feral youth – orgiasts of inner emptiness – on the rampage. On the other, we have an uneducated workingman who felt compelled to trudge ten miles so his occasional lady customers were provided with paper, and who thereby may have enabled some moment of inspiration now enshrined as a permanent monument of the Western mind. Notice, moreover, how neatly and elegantly this “poor working man” expresses himself (compare Sean Penn’s barely literate prose here). Consider what this language implies about life in a remote nineteenth-century cottage; consider the mental and social order that it presupposes. Consider also what it implies about our own families and schools, neither of which tend to produce anything resembling basic literacy. What mental and social order does this failure presuppose? Language emerges to express meaning; in the absence of meaning, it does not emerge.

The apologists of the rioters will say they are victims of capitalism, of recession, of poverty, of a society “that doesn’t care”; they will note that the nineteenth century had mobs and riots of its own (not such nihilistic ones, I would say). “There are people here with nothing,” declares one rioter, to which Theodore Dalrymple – prison physician turned essayist – responds:

[N]othing, that is, except an education that has cost $80,000, a roof over their head, clothes on their back and shoes on their feet, food in their stomachs, a cellphone, a flat-screen TV, a refrigerator, an electric stove, heating and lighting, hot and cold running water, a guaranteed income, free medical care, and all of the same for any of the children that they might care to propagate.

What did the old shop-owner have but pride and amity? For that matter, what did Charlotte Bronte have? Not much in terms that a rioter would understand, but everything in a larger sense. Her possessions – indeed her wealth – included family, culture, and religion, a conviction of duty and purpose, a sense of meaningful if obscure place within an ordered scheme of society and reality.

Posted August 16th, 2011 at 11:23am.

That was beautifully written. I especially enjoyed this thought and the way in which it was expressed: “Language emerges to express meaning; in the absence of meaning, it does not emerge.”

In my opinion Clockwork Orange is quintessential Kubrick and it’s my favorite of all his movies. Kubrick was one of the great directors of our lifetime. I just wish he had done more movies before he died.

I confess to not really liking A Clockwork Orange, in fact I rather intensely disliked it. As I admire most of Kubrick’s other films, I am curious why that is, when so many others liked it. I found it grim, ugly, and unpleasant, but more importantly, manipulative. It shows all the horrible things Alex does and gets us to hate him, then it shows horrible things done to him, and gets us to sympathize with him. All this apparently just to prove the point that taking away freedom of choice is a bad thing. Well, I could have told you that, and without putting you through such a wringer. Kubrick seems intent on shocking his audience, and he sometimes succeeds, but he also disgusts and irritates me, and the constant nudity becomes boring rather than shocking. He is/was a genius, so he succeeds in manipulating my emotions easily, but it’s such a violent, forced manipulation, in the service of such a small goal, that I greatly resent it.

Can someone explain to me why they think it’s a great film, and what it has to say to conservatives, other than violent nihilistic gangs are bad?

You make good points, and it’s definitely a legitimate interpretation of the film. Kubrick rather infamously changed the ending of Burgess’s novel, rendering it somewhat more amoral – a decision with which, needless to say, Burgess was intensely displeased (Burgess saw it a story about growing up; Kubrick saw it as… Lord knows).

First, I’ll note that I’m biased because I saw ACO when I was 18, and it was the first film that sparked that latent part in my brain which understood the difference between great movies and other movies. I spent the entire Summer before I went to college watching every Kubrick movie over and over again, and had probably watched ACO a hundred times when the obsession at last petered out.

That being said, I think I can be more objective today, and I’ll give it a go. One of the things I love about Kubrick’s films is that they are powerful and unique in an aesthetic sense, but at the same time they do not play by the “Western Union” rules of messaging. I honestly can’t tell you what The Point of any Kubrick movie is. I love Full Metal Jacket, and I can analyze it to death, but when all is said and done, I have no clue what it’s really about. It’s this mysterious quality – as I like to put it, the “monolith” that Kubrick inserts in all of his films – that keeps me coming back to Kubrick.

Now, this is relevant to ACO because I’m not sure that Kubrick was trying to say simply that messing with individual freedom is bad. The title of the film/book was meant to be an implied question – Are human beings wound-up like clocks? By whom? By God? Or by man? Or by anyone? And what are the consequences of believing one set of those propositions instead of the others? Accordingly, what I get out of ACO is an almost classically structured parable (it has the most blatantly defined three acts I’ve ever seen in a film) that, as with a Greek tragedy, raises a bunch of fearful questions and provides zero answers.

If one thinks about it, the endings of 2001, ACO, FMJ, and Eyes Wide Shut ALL end with some form of “the baby” returning – Alex goes back to his infantile polymorphous perversity; the soldiers all sing the Mickey Mouse song; and Dr. Harford weeps guiltily like a busted child. Even The Shining has a shiny young Jack being “reborn” in a wacky version of Nietzsche’s eternal return. Notice as well that each of these “regressions” (to use the Freudian term) is sandwiched between a “monolith” or a mystery and the reality of “earth” – Alex’s fantasy world and the deranged England he lives in; the pop cultural-media phantasmagoria version of Vietnam and the reality of the place; the fantasy world of Dr. Harford and the reality of marriage; and the ghost world of the Overlook Hotel and the reality of madness and family breakdown. This is the grid through which I view ACO, and of course it’s just my reading of Kubrick.

So Alex is evil in Act One. Was he born evil, or, as is also suggested, was he “made” so by pervasive leniency and permissiveness?

In Act Three he is “good.” Again the idea is that he is made so by Godlike doctors redesigning his soul. He chose this, but clearly did so in order to get out of jail, not because he cared about being good. The Pavlovian experiment “works,” but his soul is not altered. On the other hand, if pleasure and pain are all there is – as denizens of a materialist dystopia would believe – how is this New Alex’s state any different from the “natural” state of Old Alex? Both are simply “clockwork” responding to the lures of pleasure and the repulsions of pain, save with reversals of the activities associated with each.

Act Two, I’d guess, is Purgatory, where Alex is exposed to God and faced with an opportunity to choose to change. We are prodded to wonder whether even a religious conversion “chosen” by Alex would not itself have been a result of some form of programming. Is the priest naive to believe that an evil man can choose to be good? We don’t know, but that’s certainly suggested.

I don’t want to get too expansive, and I suppose the point is basically clear: the movie can certainly be viewed as an argument for free will, yet it can also be viewed as an argument for its polar opposite – complete determinism. And the context of this is a materialist dystopia where science has replaced religion as “the opiate of the masses” – which I take to be a cue that we are not only supposed to ask ourselves about free will, but also about what the consequences of the ideology (if you will) of society are for free will. Perhaps we only become Pavlovian beings when we believe we are. Or perhaps believing in free will is necessary to exercising it, or exercising it in a way that is at all responsible.

The usual complaint against Kubrick is that he is a nihilist, and I can’t disagree. I can’t agree either. I gather ultimately Kubrick just loved the mystery and the way reality is both pervaded by and eludes it. Usually this comes off as adamantine amoralism, but I’d say that while it probably is that, it’s mostly a consequence of Kubrick just not being all that interested in moral questions. Rather, he was interested in the whole framework of life, which nicely captures his hubris as an auteur. The moral questions arise in the context he depicts, and we can raise any and all of them, because Kubrick is always viewing life from the roof of the cosmos, encompassing everything but not, as it were, highlighting anything.

I think ACO can be defended on purely stylistic grounds as a masterful piece of filmmaking and composition, but thematically you can get what you want out of it, as with any of Kubrick;s films (for the reasons just detailed). This is just my take on it, and I have no idea whether Kubrick would have agreed with me. Probably not. After all, God and Kubrick work in mysterious ways.

I’m in total agreement with you regarding ‘Clockwork Orange,’ Stephen, in just about every respect you touched on. I’m curious as to whether or not you’ve read Burgess’ novel; if not, let me further enumerate some of the problems of the film. In the novel, Burgess used this invented slang language – a mix of cockney English and Russian – to act as a buffer between the reader and the ultra-violence and depravity depicted in the story. The reason he did this was because he knew that to describe in everyday,modern terms what was taking place would reduce the work to simple exploitative trash and overshadow the central theme of free will and morality. Kubrick, on the other hand, went out of his way to depict the violence – sexual, physical, emotional – with almost gleeful abandon. He also, for whatever reason, chose to keep the slang terminology from the novel intact, thus reducing it to nothing more than a cheap gimmick to which it served no practical purpose at all.

Also – when Burgess’ novel was published in the United States, the American publisher made the editorial decision to excise the final chapter wherein Alex, now an adult, makes a breakthrough as to the emptiness of his adolescent appetites for destruction (I don’t think I’m giving anything away as to specifics). It was THIS edition of the book – the incomplete, American edition – that Kubrick used as the basis for his adaptation despite the fact that the British Edition was the complete, Burgess-authorized text and that Kubrick lived and shot the film in England. I believe this goes to show that Kubrick’s attraction to the material was a superficial one which would allow him to indulge his own flair for screen shock.

On a personal note, I also dislike Kubrick’s taking ownership of the material. The full title of the film is ‘Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange,’ but it ISN’T Stanley Kubrick’s – it’s Anthony Burgess’ in every respect: characters, setting, dialogue, etc.

Regarding the rioter’s line about people having nothing, and Dalrymple listing what they do have, my guess is the problem is people who are given a handout but don’t have a job don’t feel like they are part of society, they aren’t personally invested in anything (the shopkeeper was poor, but still had his own shop). As a result, when they are attacking people and things, they are attacking something they feel they aren’t part of. That might sound like I’m excusing them, I’m not, just offering up a possible explanation. The other half of the explanation, apparently (just based on what I’ve read the last couple of week), is the British legal system barely holds anyone accountable for anything. Why not help yourself if there are no consequences.

Mr. Ross –

I understand your concern regarding Kyle Smith’s column. However, it’s possible that quite a few people/pundits made the connection when the riots broke out. That doesn’t take away from your excellent post.

Tim, thanks for your thoughts. Actually I brought up the issue of Kyle’s column, not David. – Jason

That is a great piece, David.

I also have to compliment Lee, SeeSaw, and Stephen for a brilliant exchange about Kubrick. I too became obsessed with the director when I was 18, and saw “Clockwork Orange” for the first time. I had seen “The Shining” and “2001” each a few times before that, but that’s when my interest in Kubrick really took off.

Thanks Vince.

Great minds and all… 🙂

Appreciate it, Vince.

Also, I second you kudos to Mr. Ross about his excellent article

Google “clockwork orange london riots.” You’ll find that several others have made the same connection, some as many as 4 or 5 days ago. For example:

http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/8c42acba-c40f-11e0-b302-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1VK86BnTe

First, we made our editorial comment that Kyle Smith’s New York Post piece was similar to David’s earlier Libertas post because it specifically uses some of the same language, in terms of Clockwork being “prophetic” and that the rioters are conducting a “crime orgy” (Kyle’s phrase) which is pretty similar to David’s phrase “orgiasts of inner emptiness.” I do a fair bit of blogging, as you know, and certain things simply catch my attention. I’m simply asking here for a clarification.

Second, we know Kyle, we’ve met with him in person and exchanged email on several occasions, and we know he’s well aware of the site. Here he is linking to us last year, for example:

http://kylesmithonline.com/?p=6261

Third, given that, it is an unusual coincidence that Kyle’s piece would use similar language and go up eight hours later on the very same day as David’s. Maybe it is all a coincidence, in which case, all we asked for was a clarification from him.

Finally, I did do a Google search and I did not see articles that explicitly discussed the film and compared it to the London riots as David’s did, which is again why Kyle’s piece caught my eye.