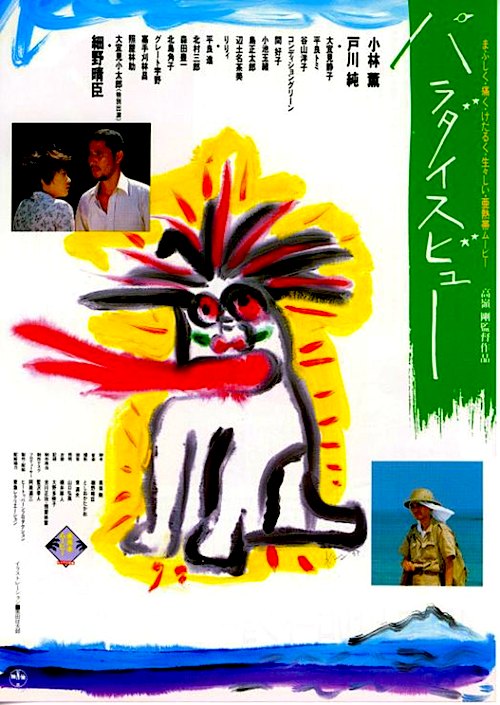

By Joe Bendel. The Vietnam War is winding down, which some would say is good news, but not necessarily on Okinawa. The separatist rebels should be pleased, but they have been quiet lately. The snakes in the jungle are as deadly as ever, but the greatest danger is losing one’s soul to the rainbow pigs secretly marauding through the rain forest. On paper, it looks like absolutely bedlam, but for the most part, the days are pleasantly languid in Go Takamine’s Paradise View, which screens today as part of the Japan Society’s Monthly Classics series.

By Joe Bendel. The Vietnam War is winding down, which some would say is good news, but not necessarily on Okinawa. The separatist rebels should be pleased, but they have been quiet lately. The snakes in the jungle are as deadly as ever, but the greatest danger is losing one’s soul to the rainbow pigs secretly marauding through the rain forest. On paper, it looks like absolutely bedlam, but for the most part, the days are pleasantly languid in Go Takamine’s Paradise View, which screens today as part of the Japan Society’s Monthly Classics series.

Okinawan is spoken throughout Paradise, making it one of the few Japanese films that required Japanese subtitles when it opened domestically. Like the periodic Welsh language film produced in the UK, it was intended as an act of Okinawan cultural affirmation and defiance. Yet, it is hard to imagine getting too worked up in this island village. Granted, nobody is happy per se, but the heat and the spirit-infested air have an anesthetizing effect. Goya Reishu is a case in point. He was once a busy musician working the American military bases, but now he just lays about, gluing teeny-tiny numbers on the ants that fascinate him.

On this island, outsiders like the ethnic Japanese botanist Ito are almost considered foreigners, even though the Japanese government is about to reassert political control of the island. However, he is still a good catch, at least according to Nabee’s mother, who happily arranges their marriage. Unfortunately, all her plans come crashing down when she deduces Nabee is pregnant with Goya’s love child. The shy Chiru is not too happy about it either, considering the torch she has been carrying for Goya. The resulting scandal is bound to end in tears, especially considering the regularity with which people in the village misplace their souls, becoming extremely apathetic mabui.

With its eccentric vibe and unhurried pace, one might also diagnose Paradise with a persistent case of indie-itis, but it never feels self-indulgently twee. Everyone is just too hardscrabble to be cutesy. Although Takamine’s strict budget constraints start to show down the stretch, he still transmits a vividly pungent sense of Okinawa as a specific place with a Shamanistic state of mind. Frankly, there is something seductive about the ebb and flow of the first two acts. You can feel the humidity clouding into your perception, while Takamine takes his time slowly implying bits and pieces of his undisciplined plot. Yet, that elliptical suggestiveness is part of the charm. When things finally start to happen definitively, it rather breaks the spell.

Kaoru Kobayashi makes an appealingly low key anti-hero as the ant-obsessed slacker, while Jun Togawa is quite touching as the lovelorn Chiru. In fact, the entire ensemble looks appropriately rugged and slightly sunstroke-addled.

Paradise View is the sort of film that insists viewers acclimate themselves to its rhythms. It really transports the receptive viewers to Okinawa, as it was prior to the Japanese Reversion. Even those who cannot synch up with its mysterious atmosphere should still appreciate the novelty of it as an example of rarely seen Okinawan cinema. Recommended for those who appreciates mystical folklore, Paradise View screens tomorrow (10/2) at the Japan Society as their classic of the month.

LFM GRADE: B+

Posted on October 2nd, 2015 at 3:08pm.