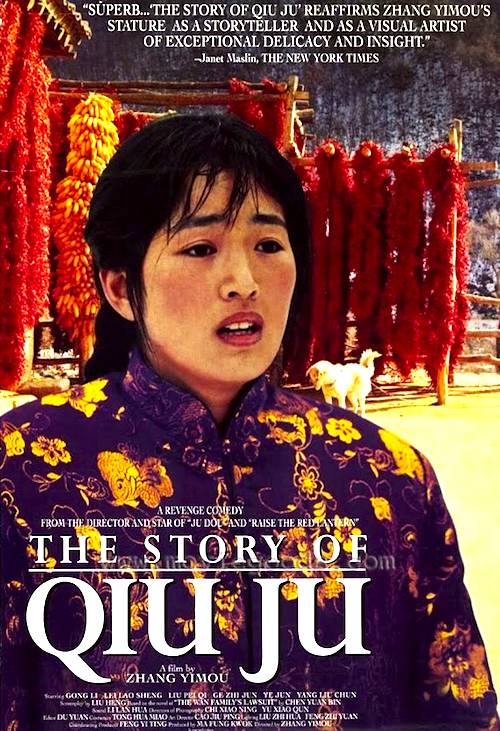

By Joe Bendel. It is hard to get around the symbolism of it all when a local village official deals a swift kick to a peasant’s family jewels. Technically, that is not considered proper behavior, but getting justice from the Party is a tricky undertaking. However, his pregnant wife is determined to extract an apology in Zhang Yimou’s The Story of Qiu Ju, which screens tomorrow as part of MoMA’s Chinese Realities/Documentary Visions film series.

A Golden Lion award winner at Venice, Zhang adapted Chen Yuanbin’s novella with a documentarian’s eye for realistic detail—hence its inclusion in MoMA’s current retrospective. Following Qiu Ju’s quest for redress, her Story makes a fitting companion film to Zhao Liang’s Petition (also screening at MoMA), even though it is considerably more ironic and less harrowing. Regardless, justice was clearly an elusive proposition in 1990’s China (and remains so today).

During a stupid argument, Wang Shantang applied said kick to Qinglai. While problematic under any circumstances, injury to Qinglai’s reproductive organ carries far greater implications for the couple due to China’s population control policies. Should Qiu Ju miscarry, they could be permanently out of luck. Regardless, Wang is not apologizing, so Qiu Ju presses her case up the administrative ladder, with little support from the sulking Qinglai.

Needless to say, Chinese officialdom is rather inclined to circle the wagons around one of its own. There is indeed a pronounced Kafkaesque element to the film. Yet, Qiu Ju is no standard issue victim. Her indomitable spirit is rather ennobling, in marked contrast to the typically depressing protagonists of Sixth Generation social issue dramas and some of their Fifth Generation forebears. Likewise, there is an unusual gender reversal afoot, in which Qiu Ju trudges from town to city for the sake of her principles, while the emasculated Qinglai hobbles about their cottage.

Needless to say, Chinese officialdom is rather inclined to circle the wagons around one of its own. There is indeed a pronounced Kafkaesque element to the film. Yet, Qiu Ju is no standard issue victim. Her indomitable spirit is rather ennobling, in marked contrast to the typically depressing protagonists of Sixth Generation social issue dramas and some of their Fifth Generation forebears. Likewise, there is an unusual gender reversal afoot, in which Qiu Ju trudges from town to city for the sake of her principles, while the emasculated Qinglai hobbles about their cottage.

In a radical change-up from her glamorous image, Gong Li (an outspoken critic of Chinese censorship) looks, sounds, and carries herself like an out-of-her-depth peasant woman. Yet, her Qiu Ju has a quiet fierceness and an affecting innocence that are unforgettable. Likewise, Kesheng Lei’s Wang makes a worthy antagonist. It is one of those slippery performances that are hard to either categorize or forget.

The Story of Qiu Ju is a significant film in Zhang’s canon and the development of Chinese cinema in the 1990’s. In a way it bridges the Fifth and Sixth Generations, despite its multi-award winning star turn from the still charismatic Gong Li. It certainly focuses a withering spotlight on contemporary China’s bureaucracy and legal system. Highly recommended for China watchers and Gong Li fans, The Story of Qiu Ju screens tomorrow night as part of MoMA’s Chinese Realities.

LFM GRADE: A

Posted on May 16th, 2013 at 10:14am.