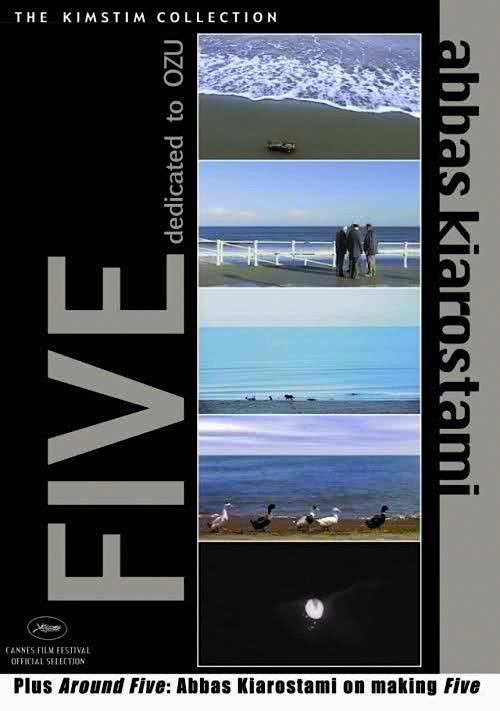

By Joe Bendel. Yasujiro Ozu had a deft touch when it came to directing children. It would therefore make perfect sense that the auteur’s work has deep resonance for Iranian filmmakers. Yet, it was the Japanese master’s so-called “pillow shots,” brief but peaceful still life transition images, that inspired Abbas Kiarostami’s tribute Five Dedicated to Ozu, which screens as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s latest retrospective, A Close-Up of Abba Kiarostami.

Also known as Five Long Takes Dedicated to Yasujiro Ozu (or simply Five), Kiarostami’s homage deliberately eschews narrative and characterization in favor of pure composition. Having premiered as a museum installation, it is best considered as part of that experimental genre. Nonetheless, for admirers of Kiarostami and his protégé Jafar Panahi, it carries additional significance as the film the former shot while they were co-writing Panahi’s politically charged Crimson Gold.

Those five long takes show the Caspian Sea, almost entirely from a fixed vantage point. In the first scene, we watch the tide drag a piece of driftwood back and forth, for a lulling effect. The following boardwalk scene also features repetitive motion as indistinct pedestrians walk through the camera’s field of vision. However, viewers might wonder at various times if perhaps Panahi has just made his reported cameo. While one would think there is nothing conceivably objectionable in Five, the many uncovered female heads in this scene would most likely be problematic in Kiarostami’s native Iran. Of course, the pace and meditative vibe of Five provides plenty of time for the audience to wonder about such matters.

Those five long takes show the Caspian Sea, almost entirely from a fixed vantage point. In the first scene, we watch the tide drag a piece of driftwood back and forth, for a lulling effect. The following boardwalk scene also features repetitive motion as indistinct pedestrians walk through the camera’s field of vision. However, viewers might wonder at various times if perhaps Panahi has just made his reported cameo. While one would think there is nothing conceivably objectionable in Five, the many uncovered female heads in this scene would most likely be problematic in Kiarostami’s native Iran. Of course, the pace and meditative vibe of Five provides plenty of time for the audience to wonder about such matters.

Considering the third take features dogs—unclean animals according to the ruling mullahs—Five probably has two strikes going against it. Presenting the frolicking canines as tiny figures on the horizon, it might be Kiarostami’s most interestingly framed shot, closely resembling an ECM album cover.

For kids who love ducks, Five might just be worth having for the fourth take of duckies waddling across the beach. Without question they are the most entertaining part of the film. For the concluding fifth take, it is frogs that are heard but not seen, as the moon rises and glimmers over the dark sea.

When most Ozu fans watch Five, their thoughts will probably wander to what those great films really mean to them. As pleasant as they might be, his work is not beloved for the pillow shots Kiarostami has so greatly expanded here. It is the exquisite dignity of Chishu Ryu’s many father figures, Keiko Kishi’s endearing sexuality in Early Spring, and most of all the legendary work of Setsuko Hara. To see her in the “Noriko” films is to fall head-over-heels madly in love with her. It is precisely that humanity that is missing from Five.

Regardless, Kiarostami most likely accomplishes what he set out to do with Five, so here it is. At least it presents an opportunity for viewers to reflect on their respect and affection for the films of Ozu and Panahi, which is something. Recommended primarily for patrons of the non-narrative avant-garde, Five Dedicated to Ozu screens this Thursday (2/14) at the Walter Reade Theater, as does his recent masterwork, the highly recommended Certified Copy starring the incomparable Juliette Binoche, as part of the Close-Up on Abbas Kiarostami career retrospective.

LFM GRADE: C

Posted on February 11th, 2013 at 3:19pm.