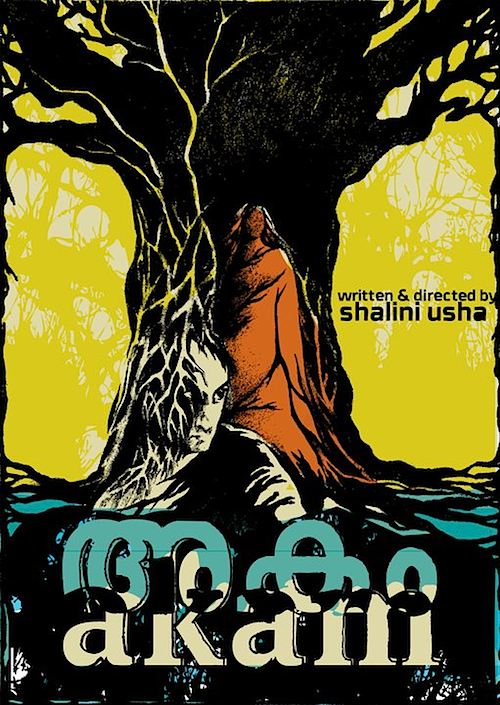

By Joe Bendel. They are known as Yakshis in southern India, but we would think of them as succubi. Every culture has their equivalent, but one architect fears he married one. Yet, his perception of reality may or may not be so reliable in Shalini Usha Nair’s Akam (Palas in Bloom; trailer here), which screened at the 2012 South Asian International Film Festival in New York.

By Joe Bendel. They are known as Yakshis in southern India, but we would think of them as succubi. Every culture has their equivalent, but one architect fears he married one. Yet, his perception of reality may or may not be so reliable in Shalini Usha Nair’s Akam (Palas in Bloom; trailer here), which screened at the 2012 South Asian International Film Festival in New York.

Srinivas seemed to have his life laid out perfectly, until an accident left the young architect visibly disfigured. Abandoned by his girlfriend, he descends into a deep existential depression. It is only the chance late night meeting with a mysterious woman that snaps him out of his lethargy. Just what Ragini was doing at his construction site at that hour is a question that will bother Srinivas in months to come, but it concerns him little during their brief courtship.

For a while everything is great, and then just as suddenly things are terrible again. Srinivas finds himself besieged by minor misfortunes and ailments that he is convinced Ragini has caused. He is convinced she is a Yakshi, who seduced him in order to torment and eventually murder him, because that is what Yakshis do.

If Ragini is a Yakshi, Nair isn’t telling. There is evidence in the film to support either conclusion, but none of it is trustworthy, because of the manner in which Srinivas’s obviously warped POV skews the film’s narrative. Indeed, Akam’s open-endedness clearly gave some SAIFF patrons fits, just as Nair intended.

Loosely based on Malayattoor Ramakrishnan’s novel Yakshi, Akam could have featured a spot of gore here and there, but Nair elected to keep it off-screen – which will further frustrate genre fans. That simply is not the tradition the film flows out of. However, there are enough hat-tips to Vertigo to inspire an angry missive from Kim Novak. Present day Kerala might seem worlds and centuries removed from Puritan New England, but Srinivas could almost be considered a Malayalam Hawthorne character, whose outward disfigurement corresponds to a spiritual disfigurement. The real horror of his story is the uncertainty over whether he is the victim or the tormentor, much like a Goodman Brown.

As Srinivas, Fahadh Faasil vividly portrays a man plagued by inner demons and insecurities, while Anumol K’s Ragini certainly suggests a woman with closely guarded secrets. Freed from traditional genre demands, Nair’s pacing is decidedly patient. Unfortunately, the frequent flashbacks are not well delineated from the present day, often causing viewer confusion. Yet, her sparing use of sound, and the film’s overwhelming sense of darkness and stillness are unusually effective. Akam has a genuinely foreboding atmosphere that makes the ambiguous gamesmanship possible.

This is definitely not Bollywood. Technically it is Mollywood, but do not expect any Malayalam musical numbers. While the austerity of Nair’s style is demanding at times, the overall vibe really gets under your skin. Though not perfect, this is a film more festival programmers ought to consider. Recommended for cineastes who have a taste for the macabre but prefer mood over mayhem, Akam is set to have a limited Indian release this November.

LFM GRADE: B

Posted on October 29th, 2012 at 1:36pm.