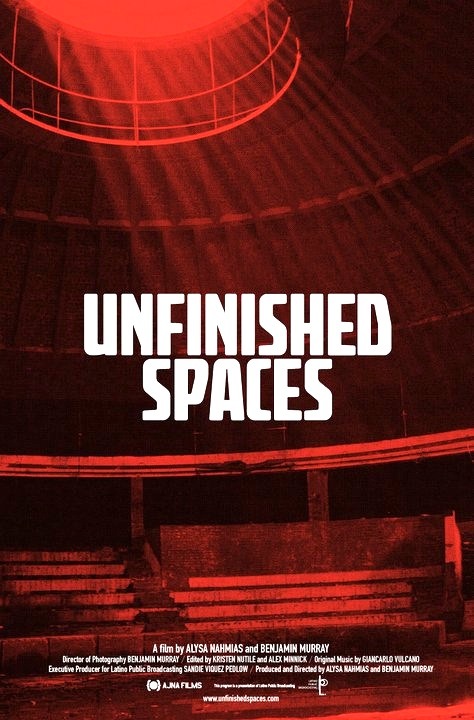

By Joe Bendel. Evidently, revolutions eventually eat their own architecture. Cuba’s National Arts Schools were intended to be the jewel in the crown of Castro’s new regime. Five buildings designed in a strikingly modern style somewhat akin to that of Brazilian Marxist Oscar Niemeyer, the complex quickly fell out of official favor and into a state of disrepair. Forty years later, two of the three principal architects returned from exile to assist the start-and-stop restoration efforts. Both celebrated and reviled by critics, the complicated legacy of the ambitious project is explored in Alysa Nahmias and Benjamin Murray’s Unfinished Spaces (trailer here), which screens during the Oscar-qualifying DocuWeeks 2011 in New York.

By Joe Bendel. Evidently, revolutions eventually eat their own architecture. Cuba’s National Arts Schools were intended to be the jewel in the crown of Castro’s new regime. Five buildings designed in a strikingly modern style somewhat akin to that of Brazilian Marxist Oscar Niemeyer, the complex quickly fell out of official favor and into a state of disrepair. Forty years later, two of the three principal architects returned from exile to assist the start-and-stop restoration efforts. Both celebrated and reviled by critics, the complicated legacy of the ambitious project is explored in Alysa Nahmias and Benjamin Murray’s Unfinished Spaces (trailer here), which screens during the Oscar-qualifying DocuWeeks 2011 in New York.

Designed by the Cuban Ricardo Porro and his Italian expatriate colleagues Vittorio Garratti and Roberto Gottardi, the National Art Schools should have been a source of enduring national pride. Instead, the poor condition of the buildings is rather embarrassing. Though most of the schools currently remain in use, routine maintenance had been almost non-existent. Unfortunately, Castro’s advisors convinced him Soviet style Brutalism was much more suitable to Communism, putting the brakes on further construction and renovations for decades. Ironically, the oppressive concrete blocks do indeed fit his ideology to a “t.” To make matters worse, Cuba’s leading diva ballerina also effectively vetoed the ballet’s school’s design when it was eighty percent complete. It remains unfinished to this day.

Of course, other minor factors further complicated efforts to complete the buildings. For instance, Garratti, the profoundly unlucky ballet school architect, was arrested on trumped-up espionage charges and eventually expelled from the country. Yet Nahmias and Murray do their best to gloss over such inconvenient details. Indeed, they argue that the greatest obstacle to a thorough restoration effort is—surprise, surprise—the American trade embargo. Indeed, Spaces’ reluctance to plum politically sensitive issues is glaringly apparent. For instance, the film never really explains the circumstances surrounding Porro’s banishment to Paris, where he has since prospered.

Straight forward in its approach, Spaces works best as an appreciation of expressionistic modernist architecture. Serving as cinematographer as well as co-director and co-producer, Murray captures all the faded beauty of the buildings, giving viewers a comprehensive sense of their character. The film also conveys an idea of what it is like to study at the crumbling campus through the reminiscences of former students, including jazz percussionist Dafnis Prieto, who also plays on the jaunty Afro-Cuban influenced soundtrack.

Strictly as an architectural documentary, Spaces is quite well produced and engaging. Yet its conspicuous timidity with respect to the wider political and historical context of the National Arts Schools leaves many obvious questions awkwardly hanging in the air unanswered. Recommended specifically for those both adept at parsing propaganda and inclined towards avant-garde aesthetics (at least in terms of architecture), Spaces screens through Thursday (8/18) at the IFC Center as part of the first wave of DocuWeeks in New York.

Posted on August 17th, 2011 at 10:40am.

The picture of that empty crumbling building pretty much sums up everything you need to know about how Communists treat artists.

Its a documentary about Architecture and not about Politics–even if politics made the architecture possible in the first place. However, without Architects (with or without politics) there is no Architecture. Like “My Architect” a documentary relying on Architecture at the lives its creators core is a rare gem indeed. To fault this film for not including an extensive dissertation on Cuban politics and the cruelty it forcibly applied to its own artists is to miss the point about the essence of Architecture and the passage of Time. The film is about universal themes, the critic here quibbles with minutiae.