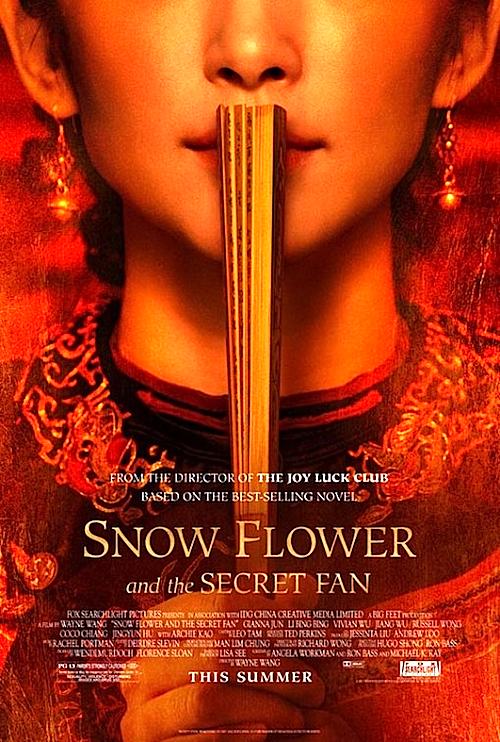

By Joe Bendel. In today’s China, girls are an endangered species. Largely due to the government’s one-child policy, sex-specific abortions and abandonments have sky-rocketed. It was not much easier for Chinese girls during the early Nineteenth Century, either. However, the Laotong (roughly translated as “Old Same”) oath of friendship helped sustain many young women. Yet the turbulence of the time will test two women’s Laotong bond in Wayne Wang’s Snow Flower and the Secret Fan (trailer here), which opens today in New York.

By Joe Bendel. In today’s China, girls are an endangered species. Largely due to the government’s one-child policy, sex-specific abortions and abandonments have sky-rocketed. It was not much easier for Chinese girls during the early Nineteenth Century, either. However, the Laotong (roughly translated as “Old Same”) oath of friendship helped sustain many young women. Yet the turbulence of the time will test two women’s Laotong bond in Wayne Wang’s Snow Flower and the Secret Fan (trailer here), which opens today in New York.

Snow Flower and Lily were born under the same sign and had their feet bound on the same day. Even though Wang waters down the literally bone-crunching reality of this practice, what the film shows is still enough to make a brawny man cringe. Unfortunately, this was considered necessary to strike a suitable marriage bargain.

Despite her family’s mean circumstances, Snow Flower’s dainty feet earn her a prestigious match. In contrast, Lily experiences the reverse social mobility, winding up betrothed to a lowly butcher after her father’s opium addiction ruins her family. Though separated by events obviously beyond their control, the two women exchange messages written within the folds of a fan, employing Nüshu, the secret script used by many Chinese women up until the Twentieth Century. (One hopes there is now an internet equivalent in widespread use today).

In parallel lives, Faye Wong Canto-pop listening high school students Nina and Sophia become a late Twentieth Century Laotong pair. Nina excels academically, while Sophia struggles emotionally in the wake of her bankrupted father’s suicide. Despite their recent estrangement, Nina puts her career on hold when a traffic accident renders Sophia comatose. As it happens, Sophia was carrying on her person a copy of her manuscript, which tells the story of Snow Flower and Lily.

Based on Lisa See’s bestselling novel, Secret Fan’s screenplay (credited to Angela Workman, Ron Bass, and Michael K. Ray) adds the contemporary story arc, allowing them to write in a part for Hugh Jackman as Arthur, Sophia’s sketchy night club impresario love interest. He even has a musical number, a novelty love song probably not designed to showcase his Broadway chops.

While Secret Fan illustrates China’s dramatic social changes, it essentially avoids political considerations. Perhaps the unsettling foot binding scene serves as an implied criticism of pre-Communistic era traditionalism. However, the go-go Shanghai of present day is essentially presented as a rather cold mercantile environment.

While the contemporary analog adds a mystical veneer to the story, Secret Fan largely aspires to high-end women’s melodrama and succeeds relatively well as such. Not surprisingly, there are few sympathetic male characters to be found in either time frame. However, the two primary leads more than hold up their ends.

Li Bingbing’s introduction to most American viewers via Secret Fan is a world away from her dynamic action turn in the forthcoming Detective Dee and the Phantom Flame, but certainly shows her range. As Nina and Snow Flower, she is quite intense and nuanced. Yet, the film’s real heart and heartstring pulling comes from Gianna Jun’s exquisitely haunting performance as Sophia and Lily.

Never shy about expressing its emotions, Secret Fan is definitely an old fashioned weeper. While the self sacrifice and noble suffering are nakedly manipulative at times, Wang deftly handles the temporal shifts and keeps the pacing rather brisk. Definitely operating in his sensitive Joy Luck Club chick flick mode, it should make several more edgy indies like Princess of Nebraska possible in the future.

A solidly respectable intergenerational drama distinguished by two very fine co-lead performances, Secret Fan is recommended to those appreciate unabashed sentimentality in film. It opens today in New York at the Angelika Film Center.

Posted on July 15th, 2011 at 1:07pm.

It sounds like it whitewashes the evils of communism. The film may be artistically well-done, but does it promote freedom?